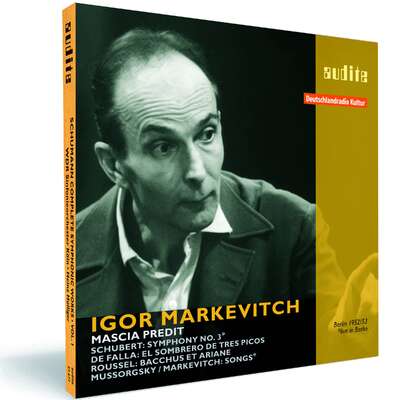

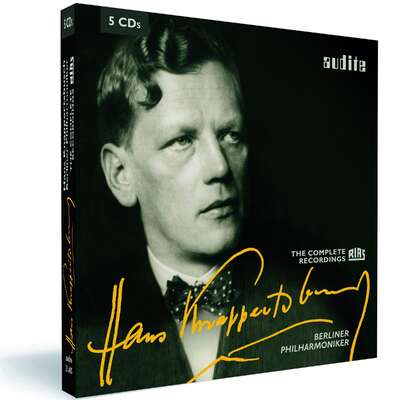

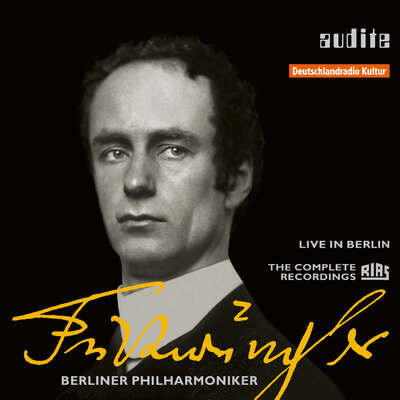

Igor Markevitch personified the modern conductor during the post-war years. For him, the most important aspects of performance were rhythmic precision, a transparent orchestral sound and a formal balance. He thus frequently managed to present works in a new perspective. In the present recordings...more

"Und das RIAS-Symphonie-Orchester, das in jenen Jahren von seinem Chefdirigenten Ferenc Fricsay zu einem absoluten Spitzenorchester geformt worden war, ist nicht nur mit Feuereifer zu erleben. Die RIAS-Musiker schienen bei den Proben die Ideen und Forderungen Markevitchs bis aufs i-Tüpfelchen verinnerlicht zu haben." (Rondo)

Details

| Igor Markevitch conducts Schubert, de Falla, Mussorgsky and Roussel | |

| article number: | 95.631 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143956316 |

| price group: | BCB |

| release date: | 26. June 2009 |

| total time: | 75 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

Igor Markevitch personified the modern conductor during the post-war years. For him, the most important aspects of performance were rhythmic precision, a transparent orchestral sound and a formal balance. He thus frequently managed to present works in a new perspective.

In the present recordings with the RIAS Symphony Orchestra made in the 1950s, Schubert’s Third Symphony is presented in a vibrant and elegant interpretation whilst the Ballet Suites by Roussel and de Falla are depicted with radiant colours and fascinating verve. Markevitch, born in Kiev, demonstrates his special affinity with Russian repertoire in his own orchestration of Mussorgsky songs which he performed with the Latvian soprano Mascia Predit in Berlin.

The production is part of our series „Legendary Recordings“ and bears the quality feature „1st Master Release“. This term stands for the excellent quality of archival productions at audite. For all historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today‘s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally competent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these.

Reviews

Fanfare | Issue 33:3 (Jan/Feb 2010) | James Miller | January 1, 2010

Born in 1911 in the Ukraine, Igor Markevitch was truly a citizen of the world, having held conducting positions in France, Spain, Monte Carlo, Italy,Mehr lesen

He’s not so easy to pigeonhole. The conductors that I think he most resembled, say, Eugène Goossens, Robert Irving, Efrem Kurtz, and Constant Lambert, have faded into the past along with him; how about Antal Dorati, with a lighter touch? I suppose it is no coincidence that all of those conductors, at least initially, made their mark as ballet maestros. There was a vigorous rhythmic component to Markevitch’s style, and ballet music made up a large fraction of his repertoire. To be sure, there are Markevitch recordings that don’t fit my characterization (an eccentric Tchaikovsky Fourth on French EMI, for example), but I think I’ll stand by my reluctant attempt to classify him. Reviews from his prime years suggest that some listeners found him too lean, too clipped in phrasing, too abrupt, maybe too “streamlined”—gemütlichkeit and angst were not his thing. He was generally a “fast” conductor.

Markevitch made studio recordings of all the selections on this disc. I never heard his Schubert Third Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic but I did hear him conduct it in person some 30 years ago. Here, with the RIAS Symphony, he will be vulnerable to complaints that, for all his energy and efficiency, he dispatches the piece in too unsentimental and businesslike a way, but some listeners may find it quite bracing. Around this time, he recorded the Three-Cornered Hat Dances with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Although there is really nothing “wrong” here, that recording is superior to this one in detail and refinement of execution. The other two selections on the disc, however, are right up his alley, really superb performances—if only they could have been done stereophonically! In the Bacchus and Ariadne Suite, his nervous energy and rhythmic drive absolutely animate the piece (not that it needs much help) and, although I have not heard his Lamoureux Orchestra recording in many years, I have a strong suspicion that it doesn’t measure up to this one—the Berliners pour it on and even hold their own with the orchestras of Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia (and I admire the Munch, Martinon, and Ormandy recordings). Unlike those of Munch and Ormandy, this one is uncut.

Mussorgsky has to be one of the great songwriters of the 19th century. Many of his 63 songs resemble folk songs. I like Leonard Altman’s explanation in an LP annotation: “Strongly inclined toward building a national style, Mussorgsky’s task was that of creating art music for a people whose natural channel of musical communication was the folk-song; the Russians were a people unaccustomed either by nature, tradition, or experience to ‘culture-music.’ That he succeeded in retaining the color and flavor of the folk idiom, and at the same time created an art music of significance to his own people as well as to the entire world, was his triumph.” During the early 1960s, Markevitch recorded his own orchestration of six Mussorgsky songs in Moscow with Galina Vishnevskaya. That performance, a very fine one, has been reissued on a two-CD set devoted to Mussorgsky’s music but, as far as I can determine, the first song, Lullabye, is missing from the reissue. In 1962, with Vishnevskaya in even better voice, he led the BBC Symphony in a superb performance that was eventually issued on CD and had better sound and playing (“had,” because it seems to have been deleted). Both of the Vishnevskaya recordings were stereophonic. Unlike some modern orchestrators of music of the past, Markevitch seems to have been more interested in serving Mussorgsky, actually enhancing the songs, than showing us how clever he could be. I was skeptical about this 1952 mono broadcast. Who was Mascia Predit? It turns out that she was a 40-year-old Latvian soprano who had at one time studied with Feodor Chaliapin. It also turns out that she had a rich voice of the Slavic type without the unpleasant edge that can seep into the top of the range and she absolutely relishes the text without destroying the melodic line. In a word, she’s terrific, and while the dynamic range is a bit more level than that of the other two recordings, the orchestra comes through clearly and plays beautifully. I also wouldn’t have minded if she were just a shade further from the mike, but, given the artistry on display here, that is a piddling point. Trivia: she appeared as a Russian tourist in the film, “Death in Venice,” under the name “Masha Predit,” and sang snatches of the Mussorgsky Lullabye, while sitting in a beach chair. I seldom make assertions of this sort but I think the six Songs may be worth the price of the disc, and you will get one heck of a Bacchus and Ariadne Suite too.

CD Compact | diciembre 2009 | Benjamín Fontvella | December 1, 2009

Markevitch fue uno de los directores más personales de la segunda mitadMehr lesen

Diapason | N° 574 Novembre 2009 | François Laurent | November 1, 2009

S'affirmant après 1945 comme un chef d'orchestre d'envergure internationale, Igor Markevitch n'oublie pas qu'il a été lancé dans le monde parMehr lesen

Reste que les musiciens de Fricsay semblent parfois pris au dépourvu par la rythmique exacerbée du chef, moins chez Stravinsky et Roussel (qui ne montre pas le konzertmeister à son avantage) que Ravel. Markevitch empoigne la seconde Suite de Daphnis et Chloé avec une violence rare – on est fixé dès le Lever du jour, où les phrasés tendus, l'influx nerveux procédant par à coups, jettent le trouble, au propre et au figuré. La conception ne variera guère dix ans plus tard au pupitre de l'Orchestre de la NDR (Emi, cf. n°523), où se retrouvent les mêmes crescendos de percussions soulignés jusqu'à la véhémence. Loin de participer à l'éclat d'une volupté dionysiaque, le choeur se fait chez Ravel rumeur inquiète, puis glaçante jusqu'à l'effroi dans la danse conclusive.

On comprendra que le Schubert de la Symphonie n° 3, vif, lumineux et «objectif», divisera la critique en 1953. Cela n'empêchera pas le chef de le fixer dans la cire avec les Berliner Philharmoniker. S'il rechigna à enregistrer ses propres œuvres après avoir renoncé à composer, Markevitch inscrivait volontiers à ses programmes son orchestration de six mélodies de Moussorgski. Le concert berlinois de 1952 en offre le plus ancien témoignage, par celle qui en donna la première audition, Mascia Prédit. Les live moscovite (Philips) et londonien (BBC

Legends) consacreront le trait plus acéré de Galina Vischnievskaïa.

Le chef anime la Symphonie «Di tre re», d'un Honegger hanté par la vision d'une humanité au bord de l'autodestruction, comme s'il y trouvait un écho à ses propres interrogations - il la gravera en 1957 pour DG. Aussi bien dans la noirceur agressive des mouvements extrêmes, où rugit la menace guerrière, que dans les faux espoirs distillés par le volet central, il nous livre une interprétation poignante, où la souffrance partout affleure, cinglant comme des coups de fouet, étouffant toute lueur d'espoir sous son halètement torturé.

Diverdi Magazin | 186/noviembre 2009 | Arturo Reverter | November 1, 2009

Tensión e impulso rítmico

Don nuevas recuperaciones del arte directorial de Igor Markevitch en Audite

Igor Markevitch dejó un gran recuerdo en España tras su años como titular de la Orquesta de la RTVE, que nació, en 1965, bajo su autoritariaMehr lesen

En su primera aparición en Madrid, allá por septiembre de 1950, frente a la Orquesta Nacional, cuando tenía 38 años, había esgrimido sus credenciales, las características que lo definían como director y que había ido fomentando desde el foso junto a los ballets de Diaghilev y más tarde al lado de Scherchen: técnica espartana y económica, gesto amplio y circular con un original movimiento alternativo de batuta y mano izquierda, curiosamente engarriada; dibujo penetrante de la música buscando siempre los puntos esenciales de cada estructura. Huía de los detalles, de establecer matices delicados, y tiraba por la calle de en medio con una certera visión del meollo, de la esencia de la partitura, que en sus manos sonaba firme, sólida, con acentos primarios y contundentes, alternados por sorprendentes fogonazos líricos.

De siempre, dadas sus condiciones, fue un magnífico organizador de los virulentos estratos de los ballets de Stravinski o de las cristalinas y ágiles composiciones de Roussel. Se lo asoció tradicionalmente con La consagración de la primavera del primero, una obra que bordaba y que en su mano sonaba agreste, dura, percutiva, invadida de una urgencia colosal; una visión auténticamente telúrica del gran sacrificio, que ofreció con la ONE en 1953 y que llevaría luego más de una vez a los atriles del conjunto radiotelevisivo, al que el director llegó, esa es la verdad, un tanto mermado de facultades, cuando solamente contaba 53 inviernos. Pero su sordera era ostensible e inevitable, lo que le hacía reforzar el nivel auditivo de los inclementes parches, que en una obra como la citada podía tener su razón de ser; no así en otras: una Primera de Brahms, por ejemplo.

La interpretación que de la partitura stravinskiana había realizado Markevitch en el Titania Palast el 6 de marzo de 1952 ante la audiencia berlinesa respondía a estos parámetros: fustigante, cortante como un cuchillo, de una extraordinaria concentración, de una soterrada energía, que terminaba por estallar violentamente en los constantes y bien controlados cambios de compás. Causó, cuenta el crítico y musicólogo Stuckenschmidt, una impresión formidable en el público, subyugado también por la orgiástica versión de la 2a Suite de Daphnis y Chloé de Ravel (registro en de 18 de septiembre), en este caso con el coro final, y que a nuestro juicio no alcanzó a recrear toda la imaginería sonora del impresionismo más pleno. Es demasiado importante en el concepto y en la ejecución el aspecto rítmico. Una impecable interpretación de la Sinfonía n° 5, "Di Tre Re", de Honegger, cuadrada y aguerrida, tensa y concisa, culmina el compacto.

El segundo combina el vivo con el estudio en grabaciones de 1952 y 1953. La Sinfonía n° 3 de Schubert es de este último año. Una aproximación precisa y vivificante, en el escenario del Titania, bien bailada, pero exenta de espíritu, de sabor vienes. El trazo nos parece en exceso grueso. El mismo año, pero en el estudio levantado en la Iglesia de Jesucristo de la capital alemana, Markevitch grababa una fogosa versión del Tricornio de Falla, vista un poco en blanco y negro, pero dotada de un impulso contagioso, y una soberana recreación de la Suite n° 2 de Bacchus et Ariane de Roussel, una partitura en nueve partes que la batuta desentraña de forma extraordinaria con un vigor, una elocuencia y un sabor danzable fuera de serie. Una interpretación auténticamente demoledora. El disco se cierra con seis canciones de Musorgski, en el arreglo orquestal del propio director, incluidas en el concierto de Le Sacre de marzo de 1952, recogido en el CD anterior. La soprano letona Mascia Predit, de la misma edad que el director, convence por su rico metal spinto, su anchura y su impronta dramática. Creemos recordar estas canciones en Madrid con Markevitch, la RTVE y la soprano polaca Halina Lukomska.

Stereoplay | Oktober 2009 | Michael Stegemann | October 1, 2009

„Bis ins letzte ausgeschliffen, jedoch etwas zu sehr mit unpersönlicher,Mehr lesen

International Record Review | October 2009 | October 1, 2009 Markevitch, Rabin, De Vito, Fricsay and Gulda on Audite

Igor Markevitch was at the height of his powers in the early 1950s and two discs of broadcast recording' with the RIAS SO, Berlin, have appeared onMehr lesen

The second disc is more interesting. It opens with the Suite No. 2 from Daphnis et Chloé by Ravel. This is very fine indeed, with Markevitch at his most engaged and expressive, and it's good to have the chorus parts included too. Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps was always one of this conductor's great specialities (he made two EMl studio recordings of the work in the 1950s alone) and here we have a live 1952 version that is staggeringly exciting and very well played. Few other conductors could deliver such thrilling versions of the Rite in the 1950s, but Ferenc Fricsay was assuredly one of them, and this was, after all, his orchestra (their own stunning DG recording was made two years after this concert). After this volcanic eruption of a Rite, the final item on the disc breathes cooler air: the Symphony No. 5 (Di tre re) by Honegger. Warmly recommended, especially for the Stravinsky (Audite 95.605, 1 hour 13 minutes).

Michael Rabin's too-short career is largely documented through a spectacular series of studio recordings made for EMI, but these never included the Bruch G minor Concerto. Audite has issued a fine 1969 live performance accompanied by the RIAS SO, conducted by Thomas Schippers, transferred from original tapes in the archives of German Radio. Rabin's virtuosity was something to marvel at but so, too, was his musicianship. His Bruch is thoughtful, broad , rich-toned and intensely satisfying. The rest of the disc is taken up with shorter pieces for violin and piano. The stunning playing of William Kroll's Banjo and Fiddle is a particular delight, while other pieces include Sarasate's Carmen Fantasy and Saint-Saëns's Havanaise. Fun as these are, it's the Bruch that makes this so worthwhile (Audite 95.607, 1 hour 10 minutes).

There have been at least three recordings of the Brahms Violin Concerto with Gioconda De Vito (1941 under Paul van Kempen, 1952 under Furtwängler and a 1953 studio version under Rudolf Schwarz), but now Audite has unearthed one with the RIAS Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Fricsay. Recorded in the Jesus-Christus-Kirche on October 8th, 1951, this is a radiant performance. De Vito's rich sound is well caught by the RIAS engineers and the reading as a whole is a wonderful mixture of expressive flexibility within phrases and a strong sense of the work's larger architecture. In this very fine account she is much helped by her conductor: Fricsay is purposeful but fluid, as well as propulsive in both the concerto and the coupling: Brahms's Second Symphony, recorded a couple of years later on October 13th, 1953. This is just as impressive: an imaginatively characterized reading that is affectionately shaped in gentler moments (most beautifully so at the end of the third movement) and fiercely dramatic in the finale. The mono sound, from the original RIAS tapes, is very good for its age. A precious disc celebrating two great artists (Audite 95.585, 1 hour 20 minutes).

Friedrich Gulda's playing from the 1950s is documented through a series of Decca commercial recordings and some fine radio recordings, including a series made in Vienna on an Andante set (AN2110, deleted but still available from major online sellers). I welcomed this very warmly in a round-up when it appeared in 2005, and now Audite has released an equally interesting anthology of Gulda's Berlin Radio recordings. Yet again, here is ample evidence of the very great pianist Gulda was at his best. There is only occasional duplication of repertoire, such as the 1953 Berlin Gaspard de la nuit by Ravel, and Debussy's Pour le piano and Suite bergamasque, immensely refined and yet strongly driven in these Audite Berlin recordings, though 'Ondine' shimmers even more ravishingly in the 1957 Vienna performance (but that's one of the greatest Gaspards I've ever encountered). The opening Toccata from Pour le piano has real urgency and tremendous élan in both versions. The Chopin (from 1959) includes what I believe is the only recording of the Barcarolle from this period in Gulda's career (two versions exist from the end of his career) – it grows with tremendous nobility and Gulda's sound is marvellous, as is his rhythmic control – it’s never overly strict but the music's architecture is always apparent. This follows the 24 Préludes. Gulda's 1953 studio recording has been reissued by Pristine, and this 1959 broadcast version offers an absorbing alternative: a deeply serious performance that captures the individual character of each piece with imagination and sensitivity.

The Seventh Sonata of Prokofiev was taped in January 1950, just over a year after Gulda had made his studio recording of the same work for Decca (reissued on 'Friedrich Gulda: The First Recordings', German Decca 476 3045). The Berlin Radio discs include some substantial Beethoven: a 1950 recording of the Sonata, Op. 101 and 1959 versions of Op. 14 No. 2, Op. 109, the Eroica Variations. Op. 39 and the 32 Variations in C minor, WoO80. Gulda's Beethoven has the same qualities of rhythmic control (and the superb ear for colour and line) that we find in his playing of French music or Chopin, and the result is to give the illusion of the music almost speaking for itself. The last movement of Op. 109 is unforgettable here: superbly song-like, with each chord weighted to perfection. Finally, this set includes Mozart's C minor Piano Concerto, K491, with the RIAS SO and Markevitch from 1953 – impeccably stylish. This outstanding set is very well documented and attractively presented (Audite 21.404, four discs, 4 hours 5 minutes).

Der Kurier | 25. September 2009 | Alexander Werner | September 25, 2009

Selbst in Kennerkreisen wird Igor Markevitch heute in seiner ganzenMehr lesen

France Musique | mercredi 23 septembre 2009 | Christophe Bourseiller | September 23, 2009 BROADCAST Musique matin

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Schwäbische Zeitung | 15. September 2009 / Nr. 213 | Reinhold Mann | September 15, 2009 Erinnerung an Igor Markevitch

Präzision, Sachlichkeit und Klangfarben sind Stichworte, die man mit denMehr lesen

Die Welt | 9. September 2009, 04:00 Uhr | Manuel Brug | September 9, 2009

[...] Weich fließende Farben werden hier gleichsam aus den TastenMehr lesen

Audiophile Audition | August 30, 2009 | Gary Lemco | August 30, 2009

Attached to the Markevitch intellectual scalpel was a driving, oftenMehr lesen

Rondo | Nr. 589 / 22. - 28.08.2009 | Guido Fischer | August 26, 2009

Der gebürtige Russe Igor Markevitch zählt bis heute zu den unbestrittenMehr lesen

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung | 25. August 2009 | Jan Brachmann | August 25, 2009

Alles ging ihm leicht von der Hand

Die Dirigentenkarriere von Igor Markewitsch begann erst nach Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs, als sein Spezialgebiet galt die Musik seines Landsmanns Strawinsky. Das „Sacre“ ist ein Glanzstück in dieser Serie von Wiederveröffentlichungen aus dem Berliner RIAS-Archiv

Mal angenommen, wir stellen uns Franz Schubert mit einer Eistüte in derMehr lesen

Scherzo | diciembre 2009 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | December 1, 2008 Gulda y otras joyas

El sello alemán Audite (distribuidor: Diverdi) nos trae un nuevoMehr lesen

www.ClassicsToday.com | David Hurwitz | December 2, -1

Recorded in 1952/53, these performances show Igor Markevitch at hisMehr lesen

News

Recorded in 1952/53, these performances show Igor Markevitch at his incisive...

Born in 1911 in the Ukraine, Igor Markevitch was truly a citizen of the world,...

Markevitch, Rabin, De Vito, Fricsay and Gulda on Audite

Markevitch fue uno de los directores más personales de la segunda mitad del...

Selbst in Kennerkreisen wird Igor Markevitch heute in seiner ganzen Bedeutung...

S'affirmant après 1945 comme un chef d'orchestre d'envergure internationale,...

Attached to the Markevitch intellectual scalpel was a driving, often explosively...

[...] Weich fließende Farben werden hier gleichsam aus den Tasten massiert,...

„Bis ins letzte ausgeschliffen, jedoch etwas zu sehr mit unpersönlicher,...

Der gebürtige Russe Igor Markevitch zählt bis heute zu den unbestritten...