These recordings of two Beethoven symphonies date from a period of change in the history of the Berlin Philharmonic. Furtwängler was again its official principal conductor, but his declining health and other personal reasons left him unable to supervise the orchestra on a continuous basis. Ever...more

"The last pages – janissary madness and superhuman ambition – tell us the Pope of Music had arrived and lived securely in Berlin." (audaud.com)

Track List

Details

| Edition von Karajan (III) – L. v. Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 ('Eroica') & No. 9 | |

| article number: | 23.414 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143234148 |

| price group: | BCA |

| release date: | 8. October 2008 |

| total time: | 123 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

These recordings of two Beethoven symphonies date from a period of change in the history of the Berlin Philharmonic. Furtwängler was again its official principal conductor, but his declining health and other personal reasons left him unable to supervise the orchestra on a continuous basis. Ever since his first encounter with the Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan wanted nothing more than to be its principal conductor. These recordings shed light on his early work with the orchestra as a visiting conductor and as the successor to Wilhelm Furtwängler.

Karajan’s first post-war concert with the orchestra, featuring Beethoven’s Eroica, on 8 September 1953 reveals not only the actual condition of the orchestra but also what Karajan was able to accomplish as a conductor in this situation. At the time Karajan was mainly busy with the London Philharmonia Orchestra and raved about its virtuosity. Yet, in the Berlin Philharmonic, he discovered dimensions that transcended virtuosity, powers of expression that went beyond rehearsal levels in the moment of performance.

At the time of the live-recording of Beethoven’s Ninth, performed in the auditorium of the Berlin Musikhochschule on 25 April 1957 to celebrate the orchestra’s seventy-fifth anniversary, Karajan was already the orchestra’s principal conductor. The orchestra was in a phase of tedious remodeling caused by Karajan’s attempts to shape the sound of the orchestra according to his musical philosophy. Beethoven’s Ninth, with a sterling quartet of vocal soloists, has a large-scale command of form and a dense, coherent sound that reveal Karajan well on his way to the first complete recording of the symphonies.

There is a “Producer’s Comment” from producer Ludger Böckenhoff about this production available.

Reviews

Fanfare | Issue 32:6 (July/Aug 2009) | Mortimer H. Frank | July 1, 2009

So many recorded concerts derived from radio tapes have proven disappointing, it comes as a refreshing surprise to hear each of these releases. MostMehr lesen

The Audite release, by contrast, is remarkable on a number of levels. For one thing, each of the symphonies it offers was recorded at a concert marking a historic event, the “Eroica” from one that comprised the first post-war public appearance of the Berlin Philharmonic, that of the Ninth occurring on the 75th anniversary of that orchestra. Musically, each is a defining point in Karajan’s approach to Beethoven. The earliest of the conductor’s surviving accounts of the “Eroica” is a 1944 performance with the Prussian State Orchestra of Berlin (possibly still available on Koch 1509). It is the broadest of the six Karajan versions that I have heard. This 1953 account is very different. In many respects it anticipates the lean, comparative fleetness of the conductor’s last (all digital) effort for DG. Indeed, it is often a more incisive version than Karajan’s recording from the previous year with the Philharmonia Orchestra. But it also features occasional rhythmic ruptures that characterized Furtwängler’s approach, albeit less extreme. Unfortunately, the sound, although ample in presence and free of tape hiss, is marred by an unpleasant metallic harshness in the strings that cannot be neutralized with a treble control. But a flexible equalizer should help to improve things. This Ninth Symphony from five years later is remarkable for the way it echoes Karajan’s first studio effort (with the Vienna Philharmonic from 1947, still available on a single EMI CD). Particularly noteworthy are the cascading, explosive legatos of the first movement and, on the negative side, some undue haste in the finale. But this live account offers greater intensity in the second movement, where a first repeat (omitted in 1947) is included. Moreover, it is sonically better than that recording, and vastly superior in that regard to the strident “Eroica” included in this set. A few bloopers from the horns simply add to the “live” ethos. Certainly, for those who admire Karajan, this release should have great appeal.

Never having heard Karajan’s EMI recording of Fidelio (1970), I cannot say how it compares to this live one of 13 years earlier. But having read unfavorable reviews of that later one, I doubt if they are similar. Put differently, this is a compelling production, laudable in several ways. The sound is better than that of many live Orfeo productions I have heard: wide in frequency response, sufficiently well balanced so that characters never seem to move too much off of the microphone, and encompassing a dynamic range, its only lack is the dimension that stereo can provide. It is the fifth live account of the opera in my collection. The others include two led by Bruno Walter at the Met (1941and 1951, both with Flagstad in a three-CD West Hill set sold only outside the U.S.), two led by Furtwängler at Salzburg (with Flagstad, 1950 and Martha Mödl in 1953, the latter on a now hard-to-find Virtuoso set, 2697272, where at one point the orchestra falls apart in the Leonore No. 3), and the fine 1961 Covent Garden production led by Klemperer, with Sena Jurinac in the title role, a kind of graduation from her many phonographic appearances as Marzelline.

This 1957 performance marked Karajan’s first summer at Salzburg and is unlike any of the others just cited, less shapeless and better disciplined that either of Walter’s, more propulsive, yet with a wider range of tempos than Klemperer’s or either of those led by Furtwängler. It also features one oddity I’ve never previously encountered: in what (presumably) may have been an attempt to avoid applause at the end of the rousing Leonore No. 3, Karajan launches immediately into the courtyard finale by cutting its opening chords and choral “Heils.” On first hearing, it comes as a shock, but it makes dramatic sense. So does the entire performance. The comparative lightness of the first act never drags, Nicola Zaccaria’s projection of Leonore’s “Abscheulicher” and “Komm, Hoffnung” aptly fierce and tender, the Prisoners’ Chorus a poignant blend of tenderness and assertion. Florestan’s act II opener, “In des Lebens Frülingstage,” may be a bit too sweet-toned for one in a dungeon, but is nonetheless superbly sung. Ironically, the kind of dreary dankness suggested in some studio recordings through the use of echo is absent here, but the scene is still compelling. And the other singers are all more than adequate. Most of all, one hears this performance not as a recording, but as a dramatic theatrical experience. Even those who own some of the other live accounts cited here (Klemperer’s is especially distinguished) would do well to investigate this one. Orfeo provides a plot summary but no libretto.

Diapason | Juin 2009, N° 570 | Thierry Soveaux | June 1, 2009

Ces documents témoignent d’un chef qui n’a pas encore forgé son idéal sonore et musical. En 1953, Furtwängler est toujours patron duMehr lesen

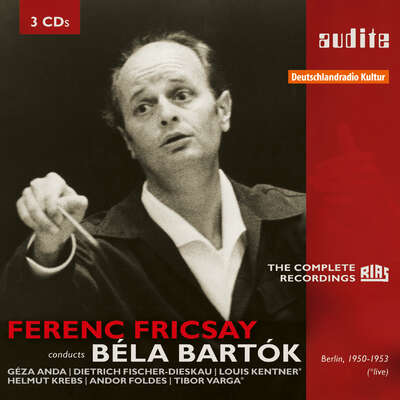

La 9e est plus affirmée, mais le discours musical manque encore de stabilité, de vraie ligne directrice; le phrasé se place davantage dans le registre de la séduction supposée plutôt que dans celui de l'émotion. Ainsi, le geste oscille entre une certaine nervosité qui frise parfois l'hystérie et une suavité trop calculée. Et puis vents et bois peu assurés font toujours preuve d'imprécision. Le chœur montre quelques insuffisances mais la voix lumineuse de Grümmer ne peut laisser indifférent. Böhm, Fricsay ou Jochum (DG), dans le même répertoire et à la même époque, tiraient un meilleur parti de cette sonorité, drue, toujours très dense de l'après-Furtwängler. Pour Karajan, il faudra attendre encore un peu.

Scherzo | mayo 2009 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | May 1, 2009 Fricsay,Karajan

Sigue la extraordinaria Edición Frícsay en el sello alemán AuditeMehr lesen

??? | February 2009 | February 1, 2009

Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

www.classicstodayfrance.com | Janvier 2009 | Christophe Huss | January 23, 2009

J'aimerais bien savoir pourquoi, alors que tout semblait bloqué en termesMehr lesen

Audiophile Audition | January 2009 | Gary Lemco | January 16, 2009

In his first post-war appearance before the Berlin Philharmonic (8Mehr lesen

L'éducation musicale | Lettre d'information n° 25 – Janvier 2009 | January 1, 2009

Les éditions Audite (www.audite.de) rééditent leurs plus célèbresMehr lesen

Journal de la Confédération musicale de France | décembre 2008 | December 1, 2008

La grande époque de Karajan. Un orchestre charnu et tour à tour, selonMehr lesen

Pizzicato | Oktober 2008 | Rémy Franck | October 1, 2008

Die Liveaufnahme der Eroica stammt aus Karajans erstem Konzert mit den Berliner Philharmonikern nach dem Krieg, im Jahre 1953. Sie ist kontrastreich,Mehr lesen

Die Welt | 20. August 2008 | Manuel Brug | August 20, 2008

Damit das voranschreitende Karajan-Jahr nicht ganz vergessen wird, gibt esMehr lesen

News

So many recorded concerts derived from radio tapes have proven disappointing, it...

La grande époque de Karajan. Un orchestre charnu et tour à tour, selon...

Ces documents témoignent d’un chef qui n’a pas encore forgé son idéal...

Les éditions Audite (www.audite.de) rééditent leurs plus célèbres...

J'aimerais bien savoir pourquoi, alors que tout semblait bloqué en termes...

In his first post-war appearance before the Berlin Philharmonic (8 September...

Die Liveaufnahme der Eroica stammt aus Karajans erstem Konzert mit den Berliner...

Damit das voranschreitende Karajan-Jahr nicht ganz vergessen wird, gibt es noch...