„In it the author no longer speaks as a subject. It almost seems as if there were a hidden author for this work, who had merely used Mahler as a mouthpiece.“ Arnold Schoenberg about Gustav Mahler‘s 9. Symphonie Rafael Kubelik became acquainted with Mahler’s music as young man, inspired...more

"In short, this is one of the finest single-disc editions of this harrowing symphony available on disc." (Andante)

Details

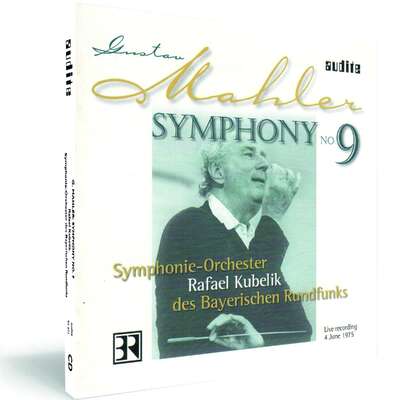

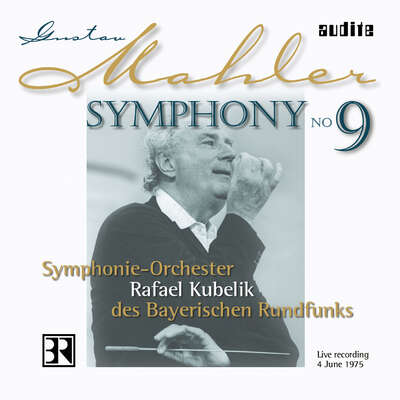

| Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 9 | |

| article number: | 95.471 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4009410954718 |

| price group: | BCB |

| release date: | 1. January 2000 |

| total time: | 78 min. |

Informationen

„In it the author no longer speaks as a subject. It almost seems as if there were a hidden author for this work, who had merely used Mahler as a mouthpiece.“

Arnold Schoenberg about Gustav Mahler‘s 9. Symphonie

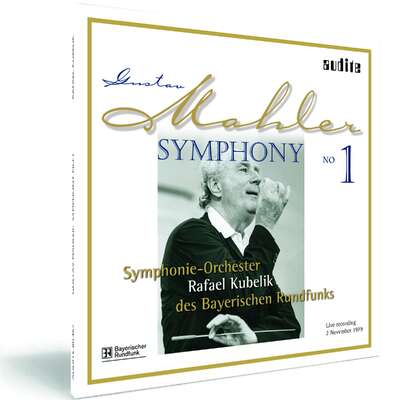

Rafael Kubelik became acquainted with Mahler’s music as young man, inspired by the work of Bruno Walter, Erich Kleiber and Fritz Busch. He was fascinated from the start by ist capacity for passion.

It was Kubelik who instigated the revival of Mahler’s work, culminating in Kubelik being the first conductor to perform a complete Mahler cycle, which took place in Munich.

This CD was recorded live on June 4, 1975 at the „Bunka Kaikan Concert Hall“,Tokyo.

Reviews

CD Compact | Abril 2005 | Benjamín Fontvella | April 1, 2005

No es fácil saber si ésta es una edición del año 2005 o unaMehr lesen

Diario de Sevilla | 24.12.2004 | Pablo J. Vayón | December 24, 2004

El exquisito sello Audite continúa con la publicación de los testimoniosMehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | January 2004 | John Quinn | January 1, 2004

Rafael Kubelik was one of the first conductors to record a cycle of Mahler’s nine completed symphonies. Those recordings, all made with the BavarianMehr lesen

In an excellent essay on the Ninth the American writer Michael Steinberg points out the parallel drawn by Deryck Cooke between this Mahler symphony and Tchaikovsky’s Sixth. In brief, Cooke suggested that in composing his Ninth Mahler had in mind the formal model of the Pathétique, noting that both symphonies begin and end with a long movement, and that in each case the finale is an extended adagio. Both composers place shorter movements in quicker tempi between these two outer musical pillars. Steinberg adds that Mahler conducted a series of performances of the Tchaikovsky symphony in early 1910, after he had completed the full draft of his Ninth. He also reminds us that, though posterity has, perhaps inevitably, imparted a valedictory quality to both works, neither composer intended these respective symphonies to be their last compositions.

This last point seems to me to be of fundamental importance in approaching Mahler’s Ninth. Yes, it is the last work that he completed fully and he was deeply superstitious about the composition of a ninth symphony. However, he had no sooner completed the Ninth than he began frantic work on a tenth symphony, which he left fully sketched out at his death. The manuscript score of the Ninth includes a number of expressions of farewell in Mahler’s hand but there are even more of these scrawled in the manuscript of the Tenth. So, while there is a strong valedictory flavour to this symphony, most especially in the last movement, I think it’s a mistake to play it as if it were an anguished farewell to music.

I say this because Kubelik’s performance may be thought by some to be lightweight because it is comparatively swift and because long passages in the last movement in particular are more flowing than we commonly hear them. However, Kubelik’s performance is by no means the swiftest on disc. Bruno Walter’s celebrated 1938 live account with the Vienna Philharmonic lasted a "mere" 70’13" but broader conceptions seem to have become more the accepted norm as the years have passed.

The first movement of this symphony is a turbulent, seething invention. Indeed, I wonder if it may be Mahler’s single greatest achievement? Kubelik exposes the music objectively and without fuss. There’s a complete absence of excessive histrionics but the music still speaks to us powerfully. This is an interpretation of integrity – in fact, that description could well suffice for the reading of the whole symphony. Kubelik has a fine ear for texture and balance, as is evidenced, for example, in the chamber-like sonorities in the passage from 6’27" to 8’40". In these pages all the orchestral detail is picked out, but in a wholly natural way. Although there are one or two overblown notes from the brass (not a trait that is evident in the other three movements) the playing is very fine and committed. There is one unfortunate flaw, however: the timpani are ill tuned at two critical points (at 6’27" and 18’00").

The second movement is an earthy ländler and Kubelik and his players convey Mahler’s trenchant irony very well. There are innumerable shifts in the character of the music and Kubelik responds to each with acuity. I would describe his work here as understanding and idiomatic.

The turbulent, grotesque Rondo – Burleske that follows is also splendidly characterised. The contrapuntal pyrotechnics of Mahler’s score come across extremely well. The pungent fast music is interrupted (at 6’25" here) by a much warmer episode in which a shining trumpet line is particularly to the fore. This episode is beautifully judged by Kubelik. The brazen coda is well handled though I must admit that I’ve heard it done with greater panache in some other performances.

A few years ago I attended a performance of this symphony in Birmingham conducted by Simon Rattle. On that occasion he launched straight into the last movement with only an imperceptible break after the Rondo. The effect was tremendous and of a piece with his searing conception of the music on that evening. I suspect that Kubelik would never have made such a gesture for his way with the finale is less overt, less subjective. In fact the start of this movement is nothing if not dignified here. As the massed strings begin their hymn-like melody, singing their hearts out for Kubelik, we are back in the sound world of the finale to the Third symphony. There’s ample weight and gravitas from the strings in these pages. The subsequent ghostly passage that commences with the wraith-like contrabassoon solo is well controlled too.

At the heart of the movement is a long threnody, carried mainly by the strings (from 6’11"). Kubelik’s tempo is quite flowing here and it’s his treatment of this episode in particular that accounts for the relative swiftness of the movement overall. Prospective listeners may want to know that he takes 22’23" for the finale. By contrast Herbert Von Karajan (his 1982 live reading on DG) takes 26’49", Leonard Bernstein, also live on DG (his 1979 concert with the Berlin Philharmonic, his only appearance with that orchestra) takes 26’12". Jascha Horenstein on BBC Legends (a 1966 concert performance) takes 26’50". Somewhat quicker overall is Rattle in his VPO recording for EMI at 24’43". It will be noted that like Kubelik’s all these performances are live ones. However, there is one important precedent for Kubelik’s relative swiftness. Bruno Walter, the man who gave the first performance of the Ninth, dispatched the finale in an amazing 18’20" in his 1938 live VPO traversal. These comparative timings are of interest. However, I must stress that though Kubelik doesn’t hang about the music never sounds rushed. The phrases all have time to breathe and there’s no suspicion that the performance is overwrought. I found it convincing. The extended climax (from 12’56") is powerfully projected. The final pages (from 17’28") are not lacking in poignancy and as the very end approaches (from 19’08") there’s a proper feeling of hushed innigkeit and tender leave-taking. Happily, there’s no applause at the end to break the spell (indeed, there’s no distracting audience noise at all that I could discern).

The recorded sound is perfectly acceptable. The acoustic of this Tokyo hall is a little on the dry side and there isn’t quite the space and bloom round the sound not the front-to-back depth that might have been achieved in the orchestra’s regular venue, the Herkulessaal in Munich. However, the slight closeness of the recording means that lots of inner detail emerges.

There’s a good deal to admire in this recording and there’s certainly an atmosphere of live music making. Above all, this release gives us another opportunity to hear a dedicated, wide and committed Mahler conductor performing a great masterpiece of the symphonic literature with authority. This is a fine version that admirers of this conductor and devotees of Mahler should seek out and hear. I hope Audite will be able to source and release more such concert performances and, who knows, perhaps build up a complete live Kubelik Mahler cycle in due course.

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

www.ClassicsToday.com | 01.01.2002 | David Hurwitz | January 1, 2002

Rafael Kubelik's excellence in Mahler can almost be taken for granted. InMehr lesen

www.andante.com | 07/2001 | Jed Distler | July 1, 2001

Audite continues to mine the vaults for its ongoing Rafael Kubelik/BavarianMehr lesen

Rondo | 6/2001 | Oliver Buslau | June 1, 2001

Lorbeer + Zitronen

Was Rondo-Kritikern 2001 besonders gefallen und missfallen hat

Meine stille Liebe:<br /> die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mitMehr lesen

die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mit

Das Orchester | 04/2001 | Werner Bodendorff | April 1, 2001

Es gibt noch glückliche Umstände, bei denen sich wirklich allesMehr lesen

Fono Forum | 4/01 | Gregor Willmes | April 1, 2001 Mahler ohne Manierismen

Im August jährt sich der Todestag von Rafael Kubelik zum fünften Mal. Die kleine, aber feine Schallplattenfirma audite pflegt sein AndenkenMehr lesen

Der Durchbruch Gustav Mahlers fand nicht im Konzertsaal statt. Zwar gab es nach seinem Tod einige Dirigenten, die wie Willem Mengelberg, Otto Klemperer und Bruno Walter Mahler noch kennen gelernt hatten und sich nachdrücklich auch im Konzertsaal für seine Sinfonien einsetzten. Doch verdankt Mahler mit Sicherheit seine Popularität zum großen Teil der Stereo-Schallplatte. Seine Sinfonien schienen wie geschaffen dazu, die Möglichkeiten der Studio-Technik darzustellen. So klingen die riesigen Sinfonien auf Tonträger oftmals sogar transparenter, als sie es im Konzertsaal je vermögen.

Leonard Bernstein war der erste, der Mitte der 60er Jahre mit dem New York Philharmonic für CBS (heute Sony) eine Gesamtaufnahme der Mahlerschen Sinfonien schuf, allerdings ohne das Adagio der unvollendeten Zehnten. Ihm folgte Rafael Kubelik, der mit dem Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks zwischen 1967 und 1971 im Herkules-Saal der Münchener Residenz alle Neune und den Adagio-Satz der Zehnten aufzeichnen ließ. Nur kurze Zeit später erschienen noch Gesamtaufnahmen von Bernard Haitink (Philips) und Georg Solti (Decca).

Ingo Harden zog im Dezember 1971 im Fono Form folgendes Fazit bezüglich der Kubelik-Aufnahmen: "Alles in allem: Der zweite vollständige Mahler-Zyklus hat in der Reihe der Mahler-Interpretationen der Gegenwart sein durchaus eigenes Profil, da sich von Bernsteins Aufnahmen durch ein Weniger an Leidenschaft und Pathos, ein Mehr an orchestraler Detailarbeit, einen helleren Grundton und eine emotional mehr den Mittelkurs haltende Darstellung unterscheidet." Harden stellte das Bild von Kubeliks "böhmischen Musikantentum" infrage, ohne es ganz abzustreiten, lobte darüber hinaus besonders die "sehr subtil und genau alle Klangfarben der Partituren aufschlüsselnden Aufführungen". In beidem ist Harden wohl Recht zu geben, wobei man nach meinem Dafürhalten allerdings Kubeliks tschechischen Wurzeln auch nicht unterschätzen soll, obwohl er sich (worauf Francis Drésel in seinem Aufsatz "Rafael Kubelik - Musiker und Poet" überzeugend hingewiesen hat) wie Mahler nach und nach "germanisiert" hat.

Rafael Kubelik wurde am 29. Juni 1914 in Bychorie bei Prag als Sohn des berühmten Geigen-Virtuosen Jan Kubelik geboren. Er studierte am Konservatorium in Prag Geige, Klavier, Dirigieren und Komposition. Er zählte also zu jener Kategorie von Mahler-Dirigenten, die wie Furtwängler und Klemperer oder wie später Bernstein und Boulez auch als Komponisten hervorgetreten sind. Das lässt vielleicht einerseits besser verstehen, warum Kubelik die musikalischen Zusammen hänge in Mahlers komplexen Sinfonien so einleuchtend darstellen konnte. Andererseits sagt das Komponisten-Dasein allein wieder auch nicht so viel über den Interpretationsstil aus, wenn man etwa an die Unterschiede zwischen Bernsteins expressivem und Boulez' analytischem Zugriff auf Mahler denkt.

Rafael Kubelik lernte Mahlers Sinfonien bereits in seiner Jugend in Prag kennen, zumeist dirigiert von Vaclav Talich,

aber auch von Gastdirigenten wie Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer und Erich Kleiber. Für Kleibers Aufführung von Mahlers siebter Sinfonie leitete der 24-jährige Kubelik 1938 sogar die ersten Proben mit der Tschechischen Philharmonie.

Schnell machte Kubelik Karriere: 1939 wurde er Musikdirektor der Oper in Brünn, 1942 Leiter der Tschechischen Philharmonie. Später übernahm er Chefpositionen beim Chicago Symphony Orchestra und an den Opernhäusern Covent Garden London und Metropolitan New York. Seine zweite Heimat - nach Prag - wurde allerdings München, wo er von 1961 bis 1971 als Chefdirigent und noch bis 1985 als regelmäßiger Gast das Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks zu außergewöhnlichen Erfolgen führte.

Laut Erich Mauermann, dem damaligen Orchesterdirektor, war Kubelik der erste Dirigent der in München einen kompletten Mahler-Zyklus durchführte. Da er Mahlers Werke immer wieder auf den Spielplan setzte, sind einige Konzertmitschnitte erhalten, die jetzt nach und nach bei audite auf CD erscheinen. Friedrich Mauermann, Bruder von Erich Mauermann und mittlerweile in den Ruhestand getretener Ex-Chef von audite Schallplatten, hat die Reihe initiiert und dabei auf das Archiv des Bayerischen Rundfunks zurückgegriffen. Bei den Sinfonien eins, zwei und fünf hatte er sogar jeweils die Auswahl zwischen zwei verschiedenen Mitschnitten. "Wenn mehrere Aufnahmen derselben Sinfonie vorhanden waren", so Mauermann, "habe ich immer die jüngere genommen. Einerseits wegen des besseren Klangbildes, andererseits wegen der musikalischen Qualität. Die Gesamtzeiten der jüngeren Aufnahmen sind generell länger als die der älteren. Die Musik atmet mehr."

Die bisher veröffentlichten Mitschnitte der Sinfonien eins, zwei, fünf, sieben und neun stammen aus den Jahren 1975 und 1982 und wurden bis auf die neunte alle im Münchner Herkules Saal aufgenommen. Folgen sollen noch Mitschnitte der Sinfonien drei (1967) und sechs (1968), ebenfalls aus dem Herkules-Saal.

Somit stammen die bis jetzt vorliegenden Aufnahmen aus einer Zeit, die nach den Grammophon-Aufnahmen liegt. Und sucht man nach grundsätzlichen interpretatorischen Unterschieden, so stößt man zuerst auf die von Mauermann erwähnten langsameren Tempi der späteren Fassungen. Die "beiläufige" Schnelligkeit, die man den DG-Einspielungen bisweilen vorgeworfen hat, sind abgelegt. Vor allem in den Adagio- und Andante-Sätzen wählt Kubelik in späteren Jahren langsamere Tempi, beispielsweise im dritten Satz der ersten Sinfonie, aufgenommen am 2. November 1979. "Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen" lautet die Satzbezeichnung, die Kubelik genau beachtet. Wunderbar baut er die Spannung auf, spielt das Crescendo aus, das allein durch das ständige Hinzutreten neuer Instrumente erreicht wird. Das Oboensolo ist überaus deutlich phrasiert, bildet im betonten Staccato einen Kontrapunkt zum Legato der Streicher. Das Parodistische des Satzes ist wesentlich besser getroffen als in der DG-Einspielung. Auch das "Ziemlich langsam" (Ziffer 5) wirkt in sich schlüssiger, man meint auf einmal einen Spielmannszug oder eine Klezmer-Kapelle zu hören.

Herrlich sind auch die ersten beiden Sätze des audite-Mitschnitts gelungen: "Wie ein Naturlaut" - kaum ein Dirigent

dürfte Mahlers Vorstellungen beim Beginn des ersten Satzes wohl so gut getroffen haben wie Kubelik in diesem Konzert. Dass die Stelle hier wesentlich überzeugender wirkt als in der DG-Einspielung, liegt auch in der Aufnahmetechnik begründet. Bei der Grammophon klingen die Stimmen isolierter, in der späteren Rundfunk-Aufnahme verschmelzen sie stärker: Das mindert etwas den analytischen Ansatz, verstärkt jedoch die Unmittelbarkeit der Naturstimmung. Hinzu kommt, dass das Orchester, besonders die Bläser, in der späteren Aufnahme noch souveräner wirken als in der ersten. Dass es sich um einen Konzertmitschnitt handelt, geht nirgendwo auf Kosten der künstlerischen Qualität. Das spricht für eine intensive Probenarbeit.

Die wesentlich bessere Aufnahmetechnik ist übrigens ein Charakteristikum, das fast alle audite-Produktionen auszeichnet. Die Konzertmitschnitte besitzen mehr räumliche Tiefe. Während die DG-Aufnahmen sehr auf Transparenz bedacht sind und immer wieder einzelne Instrumente oder Gruppen nach vorn ziehen, meint man bei den Rundfunkmitschnitten, wirklich ein Orchester im Saal der Residenz zu erleben. Und die Live-Aufnahme der neunten Sinfonie aus Tokios Bunka Kaikan Concert Hall klingt im Vergleich deutlich flacher als die Münchner Aufnahmen.

Was Kubeliks Mahler-Aufnahmen auch noch denen bei audite - gelegentlich fehlt, das ist die mitreißende Kraft, mit der sich etwa Bernstein in die schnellen Sätze warf. Das Finale der ersten Sinfonie ("Stürmisch bewegt") beispielsweise oder der zweite Satz der ansonsten interpretatorisch überzeugenden fünften ("Stürmisch bewegt, mit größer Vehemenz") weisen in dieser Hinsicht Defizite auf.

Den stärksten Eindruck der audite-Mitschnitte hinterlassen nicht zufällig jene Sinfonien, die solche Satzcharaktere

weitesgehend aussparen: die zweite und die siebte Sinfonie. So war der 8. Oktober 1982 ein wirklicher Glückstag für die Geschichte der Mahler-Interpretation. Denn Kubelik dirigierte die zweite an diesem Tag wie aus einem Guss: Alles fließt, nichts wirkt forciert im Allegro maestoso. Ein ungemein feinsinniges, schwereloses Musizieren zeichnet das Andante aus. Herrlich setzt Kubelik das Scherzo um. Das böhmisch-mährische Musikantentum - dem Ingo Harden einst so zweifelnd gegenüberstand - ist hier prächtig zu finden. Die Fischpredigt hält Kubelik leider nicht ganz so ironisch wie Bernstein. Dafür hat er mit Brigitte Fassbaender einen Alt, der das "Röschen rot" mit hinreißendem Timbre und klarer, sinnhaltiger Artikulation versieht. Im hervorragend gesteigerten Finale bilden Edith Mathis und Brigitte Fassbaender ein Traumpaar.

Genauso überragend ist die gerade auf CD erschienene siebte Sinfonie gestaltet. Sehr organisch meisterte Kubelik am 5. Februar 1976 die ständigen Tempowechsel im ersten Satz. Zauberhaft, dunkel getönt kommen die Nachtmusiken auf CD daher. Das Scherzo nimmt von Anfang an gefangen und lässt den Hörer nicht mehr los. Selbst das apotheotische Finale, mit dem viele Dirigenten Probleme haben, klingt bei Kubelik sinnvoll. Das Pathos wirkt nicht übertrieben, aber die Zuversicht bleibt.

Fazit: Mit diesen Mahler-Veröffentlichungen ist audite ein großer Wurf gelungen. Und wer bei Kubelik auf den Geschmack gekommen ist, der kann bei demselben Label auch noch hervorragende Mitschnitte von Beethoven- und vor allem Mozart-Konzerten bekommen, die Clifford Curzon mit dem Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks unter Kubelik in der Residenz gegeben hat. Aber Clifford Curzon ist schon wieder ein Thema für sich.

Klassik heute | 3/2001 | Hanspeter Krellmann | March 1, 2001

Kubelik war hierzulande Ende der sechziger, Anfang der siebziger JahreMehr lesen

Coburger Tagesblatt | 19.02.2001 | J. B. | February 19, 2001 Kubelik als Mahler-Interpret

Er war ein Dirigent mit bemerkenswerten internationalem Renommee, alsMehr lesen

Rondo | 25.01.2001 | Christoph Braun | January 25, 2001

Vielleicht sollte man sich, wenn das Jahr noch so jung und vollerMehr lesen

fermate | Heft 20/1 | Christoph Dohr | January 1, 2001

Ohne Rafael Kubelik und das Sinfonieorchester des Bayerischen RundfunksMehr lesen

Musikmarkt | 37/2000 | December 1, 2000

Rafael Kubelik (1914-1996) hat als Chef des Sinfonieorchesters desMehr lesen

Pizzicato | 12/2000 | Rémy Franck | December 1, 2000 Todes-Symphonie

Wie schon in den Symphonien Nr. 1 und 5, die dieser Neunten vorausgingen, zeigt sich Raphael Kubelik auch in diesem Konzertmitschnitt wieder alsMehr lesen

Es ist schon aufregend, wie er den ersten Satz der 9. Symphonie mit seinen Todesahnungen so überaus zerklüftet darstellt. Auch das Täppisch-derbe des Ländlers wird bestens zum Ausdruck gebracht. Die Rondo-Burleske kommt sehr burschikos daher und in der Dezidiertheit der Musik, positiv zu wirken, wird dann doch deutlich, dass das alles nur erzwungene Fassade ist, Galgenhumor, wie es Mengelberg formulierte. Der etwas stockende Beginn des letzten Satzes schließlich reißt uns sofort in die Weit des Abschieds zurück, die diese Symphonie wohl für Mahler bedeutete. In einem enormen Kraftakt lässt Kubelik Mahler im Adagio mindestens zehn Mal sterben. Selten ist mir dieser Satz so unter die Haut gegangen wie in dieser Aufnahme. Selten ist langsames Sterben musikalisch überzeugender und packender dargestellt worden als in dieser exzeptionellen Interpretation.

Die Presse | 15837 | Wilhelm Sinkovicz | December 1, 2000

Rafael Kubelik war einer der großen Vorkämpfer für die MahlerMehr lesen

Crescendo | 12/2000 | TR | December 1, 2000

Mit zwei weiteren Konzertmitschnitten von Rafael Kubelik gelingt es AuditeMehr lesen

Monde de la Musique | Décembre 2000 | Patrick Szersnovicz | December 1, 2000

Passionnément admirée et commentée par Alban Berg, la Neuvième Symphonie (été 1909) qui commence, comme on l'a souvent dit, là où se leMehr lesen

Après une remarquable Cinquième Symphonie et une splendide Première (« Choc »), toutes deux enregistrées « live » à la Herkulessaal de la Résidence de Munich, Audite Schallplatten propose un nouvel inédit de ce cycle de concerts Mahler/Kubelik/Radio bavaroise, enregistré le 4 juin 1975 au Bunka Kaikan Concert Hall de Tokyo. Plus subtil, plus « libre » que dans son enregistrement de studio avec le même orchestre (DG), Rafael Kubelik offre une Neuvième Symphonie sobre, raffinée, exemplaire par la clarté, la mise en valeur de la complexité polyphonique et par une réflexion aiguë sur l’équilibre des tempos. Si les deux mouvements médians sont moins anguleux, oppressants que dans les deux versions de Bruno Walter ou qu’avec Klemperer, Horenstein, Ancerl, Mitropoulos, Sanderling, Abbado ou Bernstein/Concertgebouw, le sens de la respiration, de l’articulation dans l’essentiel premier mouvement et dans le finale aboutit à des résultats incisifs et étonnants, quoique bien différents et sans doute moins fiévreux que ceux des enregistrements de Barbirolli/Berlin (EMI) ou de Bernstein/Berlin (DG). Comme avec Karajan/Berlin « live » (DG, le must), mais sans atteindre le même souffle ni la même urgence visionnaire, chaque note, chaque timbre est pensé avec autant de souplesse que de rigueur, le discours traçant, dans un climat plus fantasmagorique que survolté, de longues lignes lyriques d’une poésie parfois presque minimaliste.

Classica | Novembre 2000 | Luc Nevers | November 1, 2000

Après les Symphonies no 1, no 4 et no 5, captées en concert et qui nousMehr lesen

Video Pratique | Novembre-Decembre 2000 | Michel Jakubowicz | November 1, 2000

Captée à Tokyo en 1975, cette symphonie crépusculaire est l'ultimeMehr lesen

Musikwoche | 09.10.2000 | October 9, 2000

Neben Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan, Otto Klemperer oder BrunoMehr lesen

www.buch.de | August 2000 | Olaf Behrens | August 21, 2000

Die neunte Symphonie von Gustav Mahler ist seine Aschiedssymphonie. ErMehr lesen