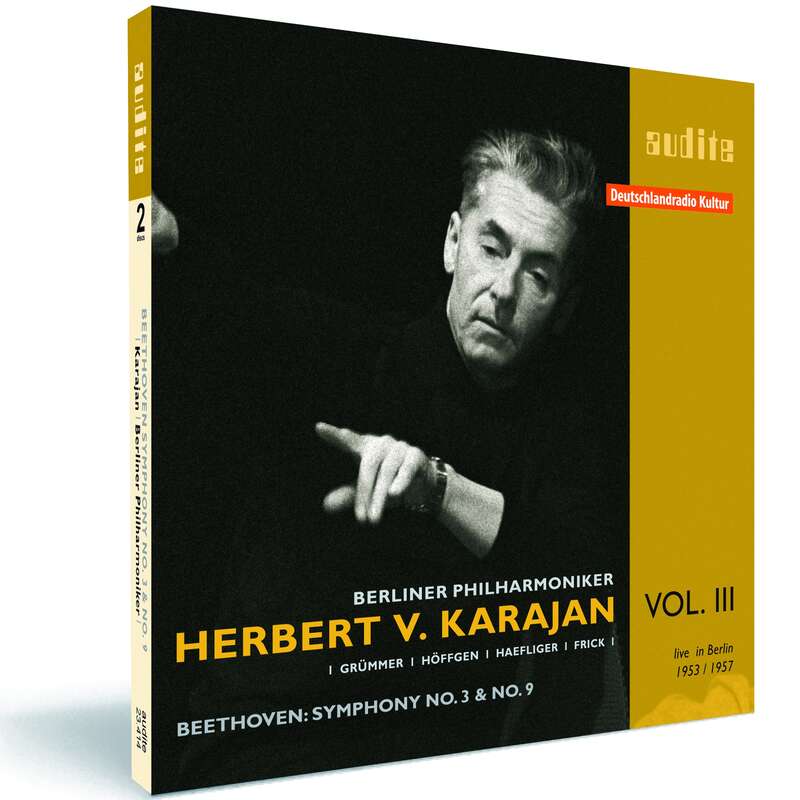

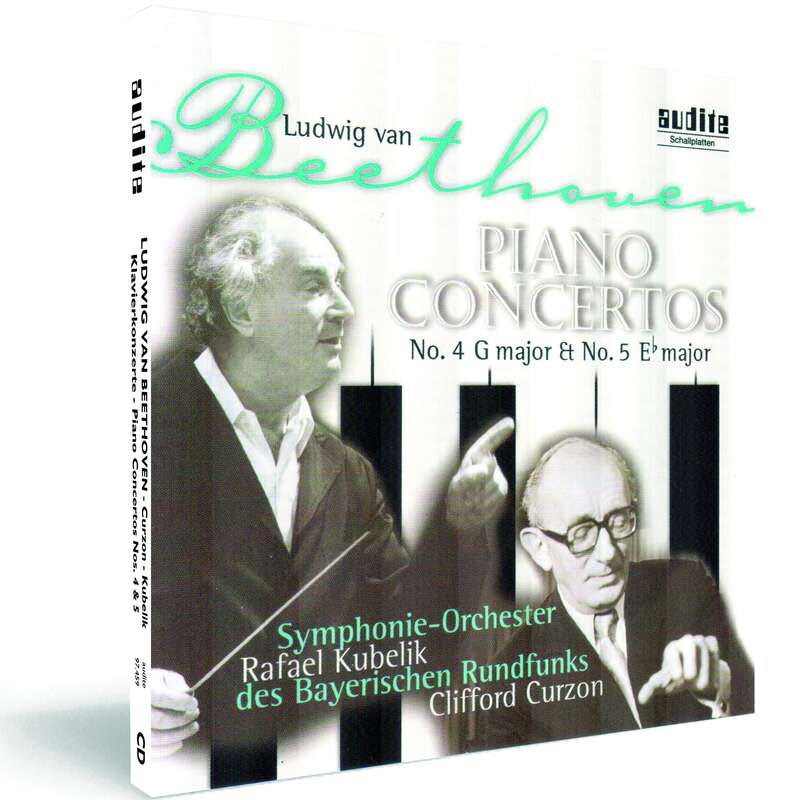

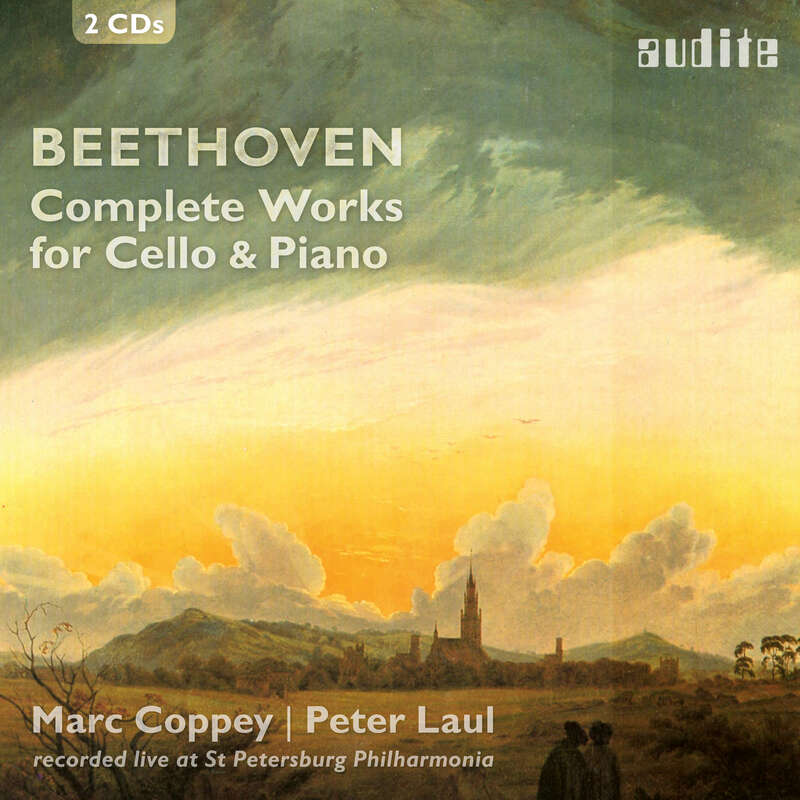

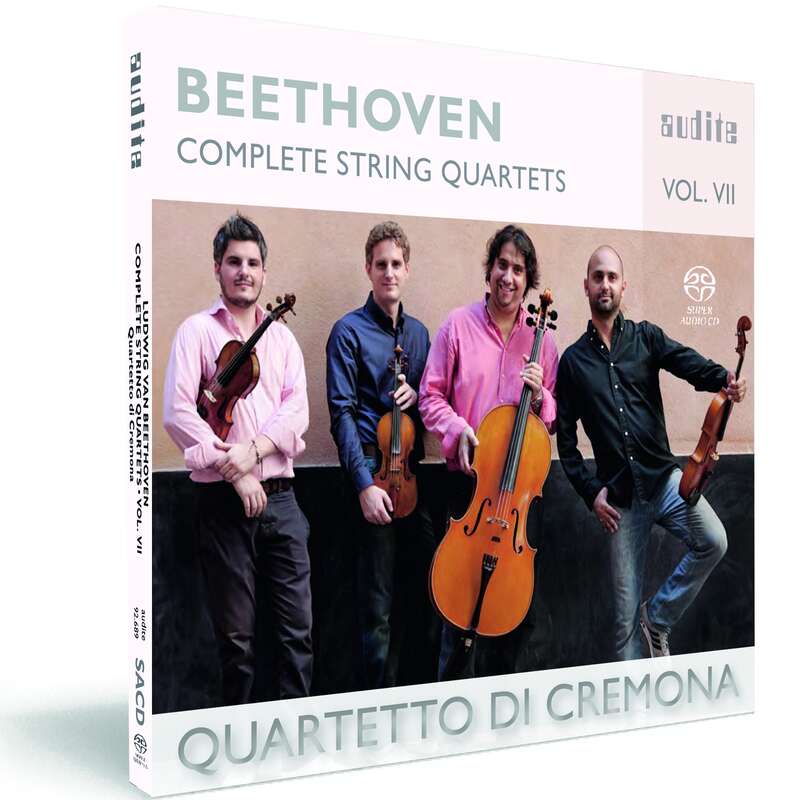

Our Beethoven series specially compiled for the 250th anniversary includes 7 recordings (4 CDs, 2 double CDs and a SACD) with Symphonies (Karajan, Böhm), Piano Concertos (Kubelik/Curzon & Böhm/Backhaus), Piano Sonatas (Oh-Havenith), the Complete Works for Cello and Piano (Coppey/Laul), Stringmore

Herbert von Karajan | Rafael Kubelik | Karl Böhm

"The last pages – janissary madness and superhuman ambition – tell us the Pope of Music had arrived and lived securely in Berlin." (audaud.com)

Track List

Multimedia

- Producer's Comment [german]

- Concert reviews of the Beethoven-Symphonies No. 3 & No. 9 (1957/1953)

- digibooklet Beethoven Piano Sonatas

- Portrait Jimin Oh-Havenith: Chrismon (April 2020)

- digibooklet

-

Peter Laul & Marc Coppey about the concept of the release

in German, English and Russian

- digibooklet

-

Quartetto di Cremona - winner ECHO Klassik 2017

Quartetto di Cremona - winner ECHO Klassik 2017

- Producer's Comment [german]

- 95598: Pizzicato Award

Informationen

Our Beethoven series specially compiled for the 250th anniversary includes 7 recordings (4 CDs, 2 double CDs and a SACD) with Symphonies (Karajan, Böhm), Piano Concertos (Kubelik/Curzon & Böhm/Backhaus), Piano Sonatas (Oh-Havenith), the Complete Works for Cello and Piano (Coppey/Laul), String Quartets (Quartetto di Cremona) and Arrangements of Folk Songs (Fischer-Dieskau): a representative cross-section of audite's extensive Beethoven repertoire.

Reviews

Klassiek Centraal

| 16 december 2020 | Erik Langeveld | December 16, 2020 | source: https://klassiek...

Beethoven als psycholoog

Jimin Oh-Havenith imponeert

Beethoven als Psychologe - Jimin Oh-Havenith beeindruckt<br /> <br /> Im Jahr 1802 vertraute Ludwig van Beethoven einem Freund, dem Geiger undMehr lesen

Im Jahr 1802 vertraute Ludwig van Beethoven einem Freund, dem Geiger und Mandolinenspieler Wenzel Krumpholz, an, dass er mit seiner Arbeit unzufrieden sei und eine neue Richtung einschlagen wolle.

Die Folgen dieser Aussage erwiesen sich als weitreichend. In der Tat verabschiedete er sich von den Grundlagen der Musik des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts und setzte dem klassischen Stil ein Ende. Zu diesem Zweck entkleidete er die Sonatenform bis auf die Knochen und stellte die Tonalität in Frage. Nach seinem Tod im Jahr 1827 sollte die Musik nie mehr dieselbe sein wie zuvor.

Die Klaviersonaten Nr. 23, 30 und 32 auf der neuen CD der deutsch-koreanischen Pianistin Jimin Oh-Havenith veranschaulichen auf faszinierende Weise die künstlerische Entwicklung dieses Komponisten, dessen Einfluss noch heute unüberhörbar ist.

Die drei Werke auf dieser CD zeigen Beethoven nicht nur als Revolutionär und musikalisches Genie, sondern vor allem auch als Psychologe.

Gemeinsam ist ihnen auch, dass sie allgemein als die berühmtesten, schönsten und schwierigsten Klaviersonaten Beethovens gelten.

Tod und Zerstörung

Die ersten Takte der Sonate Nr. 23 (1804/5), besser bekannt als Appassionata, sagen Untergang und Düsternis voraus. Beethoven entscheidet sich für f-Moll, die Tonart der Todesangst und der unergründlichen Melancholie.

Das einfache Unisono-Thema in fernen Oktaven schafft eine trostlose Atmosphäre, die durch eine Wiederholung einen Halbton höher noch bedrohlicher wird.

Es ist ein kurzes Thema, nicht mehr als vier Takte, bestehend aus einem Drei-Ton-Motiv. Während des gesamten Satzes werden wir dieses Motiv in jeder möglichen Form hören. Es wird mit einem zweiten Thema von nur vier Tönen abgewechselt, das stark an das Klopfen an der Tür erinnert, mit dem die fünfte Sinfonie eröffnet wird.

Mit diesem minimalen Material packt Beethoven den Hörer sofort. Langsam steigert er die Spannung mit schrillen Kontrasten und immer heftigeren Explosionen und testet das Instrument bis an seine Grenzen. Auf diese Weise evoziert er Unsicherheit, Zweifel und Angst und macht den Zuhörer zu einem Teil seines Alptraums.

Es kommt nicht zu der üblichen Lösung der Spannung. Wer glaubt, im zweiten Satz Andante con moto Entspannung und Behaglichkeit zu finden, wird eines Besseren belehrt.

Der Eingangschoral strahlt eine feierliche, fast religiöse Ruhe aus. Es folgen jedoch vier Variationen, in denen neben rhythmischen Verschiebungen auch immer eine Beschleunigung stattfindet. Es entsteht eine Atmosphäre des drohenden Untergangs. Die Entladung erfolgt im Übergang zum Schlusssatz Allegro ma non troppo – Presto, in dem der Hörer kopfüber mitgerissen wird in einen berauschenden, unaufhörlich fließenden Strom von Noten, durchschnitten von kraftvollen Akzenten und Synkopen. Indem Beethoven die Reprise wiederholt und die teuflische Coda hinauszögert, treibt er die Spannung auf die Spitze und trifft den letzten Schlag doppelt so hart. Der Zuhörer bleibt benommen zurück.

Die Appassionata macht deutlich, was Beethoven meinte, als er sagte, er wolle einen neuen Weg gehen. Es ist in jeder Hinsicht ein bahnbrechendes Werk, in dem Beethoven den jahrzehntelangen Kampf zwischen Form und Inhalt für immer zu Gunsten des letzteren entscheidet.

Ein großer Psychologe

Die Sonate Nr. 30 in E-Dur (1820) zeigt, wie weit sich der Komponist in nur wenigen Jahren von der Tradition entfernt hatte. Es ist die erste der letzten drei Sonaten, die Beethoven komponierte. Die Arbeit ist in jeder Hinsicht ungewöhnlich: Beethoven verlegt den emotionalen Schwerpunkt in den dritten Satz, der die vorangegangenen Sätze an Länge bei weitem übertrifft.

Der erste Satz Vivace ma non troppo – eine Art Minisonate – bietet zwei kontrastierende Themen, jedoch in unterschiedlichen Tempi. Die anfängliche Gelassenheit des Themas wird bald durch Passagen unterbrochen, in denen Beethoven seiner Fantasie freien Lauf lässt.

Auf das noch kürzere, energische Presto folgt der Höhepunkt der Sonate: das Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo mit sechs Variationen. In den ersten Variationen ist die Herangehensweise noch traditionell, aber allmählich wird klar, dass Beethoven diese Form für eine neue Art von psychologischem Plan nutzt. Ausgehend von einem korallenartigen Thema führt er den Hörer, mal sanft tänzelnd, mal mit harter Hand, in unbekanntes Terrain. Die Schichtung nimmt zu und die Wiedererkennbarkeit des Themas verschwindet, um einer Traumwelt Platz zu machen. Eine Fuge führt den Hörer zurück in das vertraute Territorium des Anfangsthemas, aber erst nach einem heftigen Orgelpunkt, in dem das Klavier bis zum Äußersten getestet wird, kehrt Ruhe ein.

Der Tod der Sonate

Nach der Sonate Nr. 32 in c-Moll (1821/22) komponierte Beethoven, abgesehen von den Diabelli-Variationen, nicht mehr für Klavier. Er empfand das Gerät als unzureichend und nicht den Anforderungen gewachsen, die er an es stellte.

Es ist ein geheimnisvolles Werk, das wegen seiner zweiteiligen Form rigoros mit dem klassischen Ideal der dreiteiligen Sonate bricht.

Im ersten Satz Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato schafft Beethoven mit wenigen Mitteln eine monumentale Struktur. Ein kraftvolles Thema bzw. ein dreistimmiges Motiv wird in jeder Hinsicht meisterhaft umgesetzt. Sie bildet den Treibstoff für erhebliche emotionale Eruptionen. Von einer Sonatenform ist nichts mehr übrig.

Ebenso wie in der Sonate Nr. 30 stellt Beethoven im Finalsatz Arietta dem Hörer die Form der Variation als Vehikel für den Ausdruck seiner tiefsten Gefühle vor.

Der Satz beginnt mit einem schönen Thema voller Resignation, bewegend, meditativ, aber die Ruhe ist trügerisch. Die Intensität nimmt zu, sowohl im Metrum als auch im Rhythmus. Es folgt ein Ausbruch von durchlaufenden Synkopen, die von Fugenfragmenten durchsetzt sind. Plötzlich wird eine unwirkliche, ruhige Atmosphäre durch einen langgezogenen Orgelpunkt und ferne, tropfende Töne geschaffen. Ist das das Geräusch im Kopf des tauben Komponisten, nur unterbrochen von Klangfragmenten aus der Ferne?

Eine Lösung hängt in der Luft, doch stattdessen steigert Beethoven durch eine bizarre Passage mit langen Schwingungen die Spannung noch weiter, um sie in einer finalen wellenförmigen und treibenden Variation zu entladen. Wieder einmal kehrt das Thema zurück, begleitet von Vibratoren. Dann endlich folgt die Auflösung und die Musik verklingt sanft.

Jimin Oh-Havenith überraschte uns letztes Jahr mit einer beeindruckenden Schubert/Liszt-CD. Dass dies kein Zufall war, hören sie nun bei dieser nicht minder beeindruckenden Beethoven-Interpretation.

Es sind bekannte Werke, die schon hunderte Male aufgenommen wurden, aber Oh-Havenith befreit sie vom Staub der Jahre und lässt sie klingen, als ob sie gerade erst entdeckt worden wären.

Ihr Spiel ist analytisch, ohne jemals akademisch zu werden, immer warm und fesselnd. Dank ihrer kontrollierten Tempi kann sie den Raffinessen und Nuancen in ihrem Spiel freien Lauf lassen. Ihr Ton bleibt voll und sonor, auch dort, wo Beethoven mit seiner extremen Dynamik und den heftigen Kontrasten das Äußerste von Interpret und Instrument verlangt.

Kein Detail bleibt dem Hörer verborgen, auch nicht in den kompliziertesten Passagen.

Oh-Havenith ermöglicht es dem Zuhörer, Beethovens musikalische und psychologische Experimente bis ins kleinste Detail zu genießen. Das macht sie zu einer idealen Beethoven-Interpretin.

-----------------------------------------

Originaltext:

In 1802 vertrouwde Ludwig van Beethoven een vriend, de violist en mandolinespeler Wenzel Krumpholz, toe dat hij ontevreden was met zijn werk en dat hij een nieuwe weg wilde inslaan.

De gevolgen van deze uitspraak zijn verstrekkend gebleken. In feite zei hij vaarwel aan het achttiende-eeuwse fundament van de muziek en maakte hij een eind aan de Klassieke stijl. Daartoe kleedde hij de sonatevorm uit tot op het bot en stelde hij de tonaliteit ter discussie. Na zijn dood in 1827 zou de muziek nooit meer zijn zoals tevoren.

De pianosonates No. 23, 30 en 32 op de nieuwe cd van de Duits-Koreaanse pianiste Jimin Oh-Havenith illustreren op fascinerend wijze de artistieke ontwikkeling van deze componist wiens invloed tot op de dag van vandaag onontkoombaar is.

De drie werken op deze cd tonen Beethoven niet alleen als revolutionair en muzikaal genie, maar vooral als psycholoog.

Ze hebben ook gemeen dat ze algemeen beschouwd worden als Beethovens beroemdste, mooiste en moeilijkste pianosonates.

Dood en verderf

De openingsmaten van Sonate No. 23 (1804/5), beter bekend als de Appassionata, voorspellen onheil en ongedurigheid. Beethoven kiest voor f-klein, de toonsoort van de doodsangst en de peilloze melancholie.

Het simpele unisono thema in ver uiteen liggende octaven schept een desolate sfeer, die nog dreigender wordt door een herhaling een halve toon hoger.

Het is een kort thema, niet meer dan vier maten, opgebouwd uit een motief van drie noten. Dat motief zullen we doorheen de beweging steeds in alle mogelijke gedaanten terughoren. Het wordt afgewisseld door een tweede thema van slechts vier noten, dat sterk doet denken aan de klop op de deur waarmee de vijfde symfonie opent.

Met dit minimale materiaal grijpt Beethoven de luisteraar meteen bij de lurven. Langzaam voert hij de spanning op met schrille contrasten en steeds gewelddadiger explosies, waarbij hij het instrument tot het uiterste beproeft. Daarmee roept hij onzekerheid, twijfel en angst op en maakt hij de luisteraar deelgenoot van zijn nachtmerrie.

Tot de gebruikelijke oplossing van de spanning komt het niet. Wie denkt in de tweede beweging Andante con moto ontspanning en troost te zullen vinden is eraan voor de moeite.

Het beginkoraal straalt een plechtige, bijna religieuze rust uit. Maar dan volgen vier variaties waarin naast ritmische verschuivingen ook steeds een versnelling optreedt. Er ontstaat een sfeer van naderend onheil. De ontlading ontstaat in de overgang naar het slotdeel Allegro ma non troppo – Presto, waarin de luisteraar halsoverkop mee gesleurd wordt in een onstuimige, non stop bewegende notenstroom, doorsneden met krachtige accenten en syncopen. Door de recapitulatie te herhalen en het duivelse coda uit te stellen voert Beethoven de spanning tot het uiterste op en komt de laatste klap dubbel hard aan. De luisteraar blijft verdwaasd achter.

De Appassionata maakt duidelijk wat Beethoven bedoelde toen hij zei dat hij een nieuw pad wilde inslaan. Het is een in elk opzicht grensverleggend werk waarin Beethoven de al decennia durende strijd tussen vorm en inhoud voorgoed beslecht in het voordeel van de laatste.

Een groot psycholoog

Sonate No. 30 in E groot (1820) laat horen hoe ver de componist zich in luttele jaren had verwijderd van de traditie. Het is de eerste van de laatste drie sonates die Beethoven componeerde. Het werk is ongebruikelijk in elk opzicht: Beethoven verplaatst het emotionele zwaartepunt naar het derde deel, dat in lengte de voorafgaande delen ruimschoots overtreft.

Het eerste deel Vivace ma non troppo – een soort minisonate – biedt weliswaar twee contrasterende thema’s, maar in verschillende tempi. De aanvankelijke sereniteit van het thema wordt al spoedig onderbroken door passages waarin Beethoven zijn fantasie de vrije loop laat.

Na het nog kortere, energieke Presto volgt het hoogtepunt van de sonate: het Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo met zes variaties. De aanpak is in de eerste variaties nog traditioneel, maar gaandeweg wordt duidelijk dat Beethoven deze vorm gebruikt voor een nieuw soort psychologisch plan. Vanuit een koraalachtig thema voert hij de luisteraar nu eens zachtjes dansend, dan weer met harde hand, mee naar onbekend terrein. De gelaagdheid neemt toe en de herkenbaarheid van het thema verdwijnt om plaats te maken voor een droomwereld. Een fuga brengt de luisteraar weer terug naar het vertrouwde terrein van het beginthema, maar pas na een woest orgelpunt waarin de piano tot het uiterste beproefd wordt, keert de vrede weer.

De dood van de sonate

Na Sonate No. 32 in c-klein (1821/22) zou Beethoven niet meer voor piano componeren, de Diabelli variaties daargelaten. Hij beschouwde het instrument als onbevredigend en niet opgewassen tegen de eisen die hij er aan stelde.

Het is een mysterieus werk dat door zijn tweedelige vorm rigoureus breekt met het klassieke ideaal van de driedelige sonate.

In de eerste beweging Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato schept Beethoven met zeer weinig middelen een monumentaal bouwwerk. Een krachtig thema of liever een motief van drie noten wordt op meesterlijke wijze op alle mogelijke manieren binnenste buiten gekeerd. Het vormt de brandstof voor flinke emotionele erupties. Van een sonatevorm is niets meer te bespeuren.

Net als in Sonate No. 30 schotelt Beethoven de luisteraar in het slotdeel Arietta weer de variatievorm voor als voertuig voor de expressie van zijn diepste gevoelens.

De beweging begint met een lieflijk thema vol berusting, ontroerend, meditatief, maar de rust is bedrieglijk. De intensiteit neemt toe, zowel in maatsoorten als ritmes. Een uitbarsting van op hol geslagen syncopen doorsneden door flarden fuga volgt. Plotseling ontstaat door een langdurig orgelpunt en veraf klinkende druppelende nootjes een onwerkelijke, verstilde atmosfeer. Is dit de ruis in het hoofd van de dove componist, slechts onderbroken door flarden geluid vanuit de verte?

Een oplossing hangt in de lucht, maar in plaats daarvan voert Beethoven middels een bizarre passage met lange trillers de spanning nog verder op om in een laatste golvende en stuwende variatie tot ontlading te komen. Nog een keer komt het thema terug begeleid door trillers. Dan volgt eindelijk de ontknoping en zachtjes sterft de muziek weg.

Jimin Oh-Havenith verraste ons vorige jaar al met een indrukwekkende Schubert/ Liszt cd. Dat dit geen toeval was laat ze nu horen met deze niet minder indrukwekkende Beethoven vertolking.

Dit zijn overbekende werken, die al honderden malen op de plaat zijn gezet, maar Oh-Havenith ontdoet ze van het stof der jaren en laat ze klinken alsof ze net ontdekt zijn.

Haar spel is analytisch zonder dat het ooit academisch wordt, altijd warm en meeslepend. Door haar beheerste tempi krijgen de verfijning en nuances in haar spel ruim baan. Haar toon blijft vol en sonoor, ook daar waar Beethoven met zijn extreme dynamiek en felle contrasten het uiterste van vertolker en instrument vraagt.

Geen detail blijft voor de luisteraar verborgen, zelfs niet in de meest gecompliceerde passages.

Oh-Havenith stelt de luisteraar in staat om tot in de kleinste details te genieten van Beethovens muzikale en psychologische experimenten. Dat maakt haar tot een ideae Beethoven vertolker.

Im Jahr 1802 vertraute Ludwig van Beethoven einem Freund, dem Geiger und

American Record Guide | November / December 2020 | Bruno Repp | November 1, 2020

I made the acquaintance of this Korean pianist, who resides in Germany, when reviewing her recent recording of Schubert and Liszt sonatas (M/A 2020).Mehr lesen

Oh-Havenith has a strong touch and controls articulation and dynamics meticulously, though I wish she would play softer sometimes. Her interpretations are not particularly subtle but authoritative. There is little to criticize. In the Appassionata her repeated notes in I are perhaps too insistent, and in both I and III she sometimes inserts “micropauses” (brief caesuras) where they are not needed.

Sonata 30 is very good. Sonata 32 stands out because of the extremely slow tempo in II. Oh-Havenith (20:52) takes more than 6 minutes longer than Wilhelm Kempff (14:31), to whose 1952 recording I listened for comparison. One result of such a glacial tempo is that the melody notes in the aria and the first variation tend to lose their connectedness; another one is that the beat is felt on a metrical level that normally would constitute subdivisions of the beat. Nevertheless, the interpretation has dignity.

The rear insert and the back of the booklet list the movements with their durations but neglect to list the tracks. There are 15 tracks because the variations of Sonata 30 are tracked separately, whereas the ones in Sonata 32 are not.

Piano News | September/Oktober 5/2020 | Anja Renczikowski | September 1, 2020

[Jimin Oh-Havenith] spielt jedes Detail aus und strahlt damit eine Ruhe aus, die überzeugt. Souverän und klanglich fein austariert spielt sie etwa die E-Dur Sonate Op. 109. Eine schön gestaltete Aufnahme, fernab des Mainstream-Musik-Business.Mehr lesen

Radio Bremen | Mittwoch, 24.06.2020, 22:04 Uhr "Klassikwelt" | Wilfried Schäper | June 24, 2020 BROADCAST

Einen schönen guten Abend und willkommen zur Klassikwelt am Mittwoch. Heute dreht sich hier alles um Ludwig van Beethoven. Das Beethoven-Jahr ist jaMehr lesen

[…]

Die Klassikwelt auf Bremen Zwei heute mit neuen Beethoven-CDs. Die Pianistin Jimin Oh-Havenith hat eine ungewöhnliche Karriere gemacht. In ihrer Heimat Korea war sie ein Wunderkind am Klavier. Sie studierte zuerst in Seoul, später dann bei Aloys Kontarsky in Köln. Lange hat sie mit ihrem Mann Raymund Havenith ein Klavierduo gebildet und viele Studioaufnahmen mit ihm gemacht. 1993 starb ihr Lebenspartner, Jimin Oh-Havenith heiratete ein zweites Mal und bekam auch ein zweites Kind. Kein Wunder, dass die Solokarriere der 1960 geborenen Pianistin erstmal in den Hintergrund rückte.

Trotz aller Probleme spielt die gebürtige Koreanerin seit einigen Jahren auch wieder solistisch. Gerade hat sie eine neue Beethoven-CD gemacht mit drei sehr bekannten Stücken: der Appassionata und den Sonaten op. 109 und op. 111. Mit diesem Repertoire begibt sich Jimin Oh-Havenith in große Gesellschaft, denn fast jeder berühmte Pianist spielt diese Stücke. Man spürt aber, dass es dieser Künstlerin um die Musik geht – alles, was sie macht, klingt authentisch und klar strukturiert. Natürlich ist Jimin Oh-Havenith keine jugendliche Sturm- und Drang-Pianistin. Sie hat sehr viel Erfahrung und spielt bei Beethoven jedes Detail aus. Ihre Tempi sind im Vergleich zu anderen Aufnahmen eher ruhig, dafür geht bei ihr aber wirklich kein Ton verloren. Besonders überzeugend finde ich Jimin Oh-Havenith in Beethovens Sonate E-Dur op. 109. Diese wunderbar poetische Musik spielt sie mit großer innerer Ruhe, klanglich sehr fein und auch technisch souverän. Jimin Oh-Havenith – eine Pianistin in ihrem dritten Frühling und eine Musikerin mit großer innerer Überzeugungskraft. Hier kommt sie mit Beethovens Klaviersonate E-Dur op. 109…

Musik op. 109 – 19´58

Jimin Oh-Havenith mit Beethovens Klaviersonate in E-Dur op. 109. Die 1960 in Seoul geborene Pianistin spielt das Stück auf ihrer neuen CD, dazu auch noch Beethovens Appassionata und die letzte Sonate op. 111. Jimin Oh-Havenith – eine Künstlerin weit ab vom Mainstream der großen Namen und eine Pianistin mit einem ganz eigenen Blick auf Beethoven. Im Juli wird die in Korea geborene Musikerin übrigens hier im Bremer Sendesaal ihre neue CD aufnehmen.

Damit geht die erste Stunde der Klassikwelt auf Bremen Zwei zu Ende. Nach den Nachrichten kommen dann zwei weitere neue CDs mit Kammer- und Klaviermusik von Beethoven. Bis gleich also, wenn Sie mögen, mein Name ist Wilfried Schäper…

www.pizzicato.lu | 14/05/2020 | Remy Franck | May 14, 2020 | source: https://www.pizz... Jimin Oh-Havenith: Interessante Beethoven-Deutungen

In diesem reinen Beethoven-Programm mit drei schwergewichtigen Sonaten zeigt sich die koreanische Pianistin Jimin Oh-Havenith als subtile GestalterinMehr lesen

Das sensible Musikantentum der Pianistin kann man durchaus als feminin bezeichnen, aber auch die Spontaneität des Interpretierens und die Wärme durchaus persönlicher Ansichten prägen diese interessanten Deutungen.

Die Tonaufnahme ist von bestechender Klarheit, ideal räumlich und präsent zugleich.

In this pure Beethoven programme with three heavyweight sonatas, Korean pianist Jimin Oh-Havenith shows herself to be a subtle performer with great lyrical sensitivity, who also succeeds in highlighting new aspects. Although she does not avoid contrasts, her playing is never austere, harsh or even loud. In addition, she has an absolutely brilliant technique, an extraordinary clarity of touch and a convincing articulation.

The sensitive musicality of the pianist can certainly be described as feminine, but we also like the spontaneity and the warmth of thoroughly personal views.

The sound recording has a great clarity, it is ideally spatial and present at the same time.

www.amazon.de | 1. September 2019 | Weidong Zhang | September 1, 2019 | source: https://www.amaz... Customer Review: Beautiful and stylish interpretation of Beethoven cello works

I have a collection of 20+ Beethoven cello sonatas and variations and this one is one of my favorites. Marc Coppey's flawless technique serves theMehr lesen

The Classical Review | May 13, 2019 | Tal Agam | May 13, 2019 | source: https://theclass... Double Review: Beethoven – Cello Sonatas – Marc Coppey, Leonard Elschenbroich

The Beethoven Cello Sonatas discography has always been very generous, yet these sonatas still stand somewhat in the shadow of Beethoven’s otherMehr lesen

Comparing the two cycles are a rewarding experience. First, these are two highly impressive and enjoyable performances. Coppey and Laul are recorded live at St Petersburg Philharmonia, and their performances are the more spontaneous-sounding of the two. Coppey’s voice has an emotional intensity that shines through even in the classical influenced Op. 5 sonatas. Laul is attuned to the dramatic contrasts in Beethoven’s piano writing and his sharp attacks are effectively conveyed when called for.

Turning to Elschenbroich and Grynyuk in the early sonatas, and you’d find a more reserved, even refined playing, with broader tempos and emotional projection in check. There is more patience in their transition from the slow introductions to the faster allegros on both of the Op. 5 sonatas. Grynyuk’s playing is honestly and simply conveyed, and the balance between the pair is superb. The results, though, is less exciting than Coppey et Laul, or less unpredictable, depending on your taste.

Elschenbroich and Grynyuk let loose some in the Op. 69, with a highly successful account of the most famous piece of the cycle. They make the best of the short Bach quote from St. Johannes Passion at the beginning of the development section, clearly see it as the highlight of the first movement. Turn to Coppey and Laul and you’ll meet an even more tumultuous Op. 69, where the development section is played with sharp attacks and direct tone that’s hard to resist. Not everyone will be convinced by the slowing down at the beginning of the Bach quote, though (6:45, track 1 in the second CD). Overall, it’s the same conundrum – Coppey and Laul are more charged with energy and with what sounds like on-the-spot decisions, while Elschenbroich and Grynyuk are calmer, organized and planned, their musical ideas projected with more subtleness. Coppey and Laul are apt for more humor in the Scherzo too, while Elschenbroich and Grynyuk are more nervous.

Elschenbroich and Grynyuk’s more reserved approach is very suitable to their take on the late Op. 102 sonatas. This is also where Grynyuk is at his best – Listen to his superb voicing at 0:55 of the last sonata’s slow movement. Coppey and Laul’s more public approach, quite literally, takes away from the music’s inwardness. Yet the fugue that finishes the cycle is prepared with a suspenseful grin, in contrast to, yet again, the seriousness of Elschenbroich and Grynyuk.

Another two impressive additions to a tough competitive catalog, then. The live set is exciting as any, with a recording that is transparent yet tends to the edginess in the loud passages. Elschenbroich and Grynyuk are better and more intimately recorded at the studio, with a more steady, reflective approach. Both deserve your attention, along with highly successful alternatives (linked below) – namely Miklós Perényi and András Schiff (ECM), Alfred Brendel and son Adrian on Phillips/Decca and Xavier Phillips and François-Frédéric Guy on little Tribeca. Not to mention the legendaries accounts by Mstislav Rostropovich and Sviatoslav Richter, or Pablo Casals’ early cycle released by Naxos.

Record Geijutsu | Nov. 2018 | November 1, 2018

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | September / October 2018 | David W Moore | September 1, 2018

Here are two identical programs handled, similar but different. The first thing I notice about Linden and Breitman is their emphasis on early musicMehr lesen

The concept is good. Unfortunately, the players don’t work closely together in phrasing; and Linden plays with notable lack of sensitivity and poor intonation. This is not as evident in the earlier works as in the later three sonatas that are really not worth hearing under these conditions. Breitman needs a better partner.

Coppey and Laul put forward a much more effective case for this great music. Their sound is well balanced, the recording much more satisfying. These recordings were made at a concert in Moscow. There seems very little audience noise and no applause, and the players are technically remarkable. Coppey plays a Goffriller cello from 1711. These two musicians play together as one, and their sensitivity for when to pause and how to make the most of Beethoven’s music is just as I would wish to play it myself. In a word, these are outstanding interpretations of some of the greatest cello music.

Marc Coppey was winner of the Bach Competition Leipzig back when he was 18 and has done well since. I loved his Bach Suites (Aeon 316; M/J 2004) and Don Vroon praised his Haydn and CPE Bach concertos (Audite 97716; J/A 2016). Here is another winner, up there with the best I have heard.

Gramophone | August 2018 | Richard Bratby | August 1, 2018

Beethoven’s solo cello music is enjoying a moment in the sun right now, with a series of excellent new recordings (including François-FrédéricMehr lesen

But while the recorded acoustic – which slightly favours the piano – is reasonably well balanced and clear, this still feels unmistakably like live performance. The tension can be exhilarating: sforzando chords explode off the page; there’s an exuberant theatricality to the extraordinary cadenza-à-deux near the end of the first movement of Op 5 No 1; and the livelier variations – as well as the Haydnesque finales of Op 5 No 2 and Op 69 – go with a headlong swagger and a swing.

In short, there’s a continual static-buzz of excitement throughout these two discs. These are performances of extremes, with a strong leaning to the extrovert, and you might prefer more of a sense of inwardness and space in the slower variations, say, or the Adagio of Op 102 No 2. Moments of reflection are rare here, and the questioning, fantastic mood that opens Op 102 No 1 doesn’t really survive the first Allegro, just as the pair never find an entirely persuasive path between lyricism and display in Op 69. Marc Coppey’s cello tone, mellow on the lower strings, can be slightly constrained at altitude, while Laul’s bright, bravura pianism leaves little scope for mystery or indeed refinement.

If asked to choose, I’d say the G minor Sonata, Op 5 No 2, is perhaps the single most convincing performance here; it’s a work that thrives on volatility and outsize gestures. This is not to belittle Coppey and Laul’s achievement, or the verve and conviction of these performances. But a thrilling live occasion doesn’t always make for a great recording, and this set is perhaps too headstrong and too relentless for endto-end listening. No one wants vanilla Beethoven but there is more subtlety to this music than you’ll find here. And, at present, it’s fairly easy to find it elsewhere.

Fanfare | August 2018 | Huntley Dent | August 1, 2018

The back story behind this new set of Beethoven’s cello-and-piano music is detailed in a personal note from French cellist Marc Coppey. He andMehr lesen

In the event, half of this partnership turned out to be exciting and charismatic, but curiously, it wasn’t the cellist. Laul, a prizewinning pianist who studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and now teaches there, takes full advantage of the equality that Beethoven provides for the piano in the last three sonatas, the middle-period op. 69 and the two enigmatic late sonatas of op. 102. His passagework is brilliant and ebullient. He phrases beautifully in the slow movements and supports the rhythm of the scherzos with brio. It’s ironic that Beethoven is acknowledged as the first important composer to take the cello seriously as a solo chamber instrument, liberating it once and for all from a drone-like existence playing continuo (although Haydn did sometimes provide more opportunities, briefly, to shine in his piano trios).

Seeming to avoid the limelight, Coppey is ill-matched to his sparkling piano partner. Much of the time he sounds recessive, which could be partially blamed on microphone placement. But engineers aren’t responsible for such plainness and lack of enthusiasm. I went back to the outstanding Beethoven set from Ralph Kirshbaum and Shai Wosner (Onyx), whom I extolled in Fanfare 40:5. A world of differences sprang from the loudspeakers—Kirshbaum produces a vibrant tone that constantly varies in color. He’s eager to shine in solo passages but also combines beautifully with Wosner’s piano part. The stylistic range of the Beethoven cello sonatas encompasses his whole career, from early Classical formality to middle-period extroversion and late-period opacity (the first movement of op. 102/1 sounds positively ugly to me). Kirshbaum-Wosner welcome the challenge to explore each style on its own terms.

But not Coppey, who has only one tone—a fairly thin, whiny, and unattractive one to my ears. As an interpreter, he has his moments, as in the allegros of the two op. 5 Sonatas and their opposite, the slow music in the two op. 102 Sonatas. I discovered only one captivating reading, of the very personal Adagio con molto sentiment d’affeto, which is the second movement of op. 102/2. Like much of the basic materials in the last two sonatas, this movement begins with a spare, unpromising theme that barely departs from a scale, yet as it unfolds and deepens, Coppey and Laul begin to commune and communicate on a moving level. Touches of this rapport appear here and there, but not enough.

I don’t feel the need to diagram the disappointing readings that the Handel and Mozart variations receive; they seem run-of-the-mill. Humor and variety are not present. As for the risk-taking and electricity that Coppey speaks of in his note, well…

I joined Steven Kruger, Jerry Dubins, and Raymond Tuttle in warmly welcoming Coppey’s arresting playing on a CD that paired the Dvořák Cello Concerto and Bloch’s Schelomo (41:2 and 41:3), all of us praising the freshness of his approach to very familiar scores. Where that artist has gone mystifies me, and perhaps others will hear virtues in this new Beethoven set that elude me. As urgently as I can recommend Kirshbaum and Wosner, Coppey leaves me cold, but with a nod to Laul for his enlivening contribution.

Diapason | N° 670 Juillet - Août 2018 | Martine D. Mergeay | July 1, 2018

Le dialogue de Manuel Fischer-Dieskau (fils de Dietrich) avec la Canadienne Connie Shih conjugue les sonorités pures, modérément vibrées et trèsMehr lesen

A I'autre bout de la galaxie, Audite confie les cinq sonates et les trois cahiers de variations au violoncelliste francais Marc Coppey et au pianiste russe Peter Laul. Les variations bénéficient, contrairement au jeu un peu maigre de Connie Shih, d'un piano ne demandant qu'a se faire Iyrique, chaleureux ou brillant, devant son partenaire (qui garde un peu plus de réserve). Forts du lien organique avec un répertoire qu'ils pratiquent ensemble depuis plus de vingt ans, Coppey et Laul habitent un Beethoven résolument romantique, porté par de grandes envolées et, pour le coup, par une tension considérable. Un tour de force dans ces tempos très lents (trop pour l'Opus 15 n° 1). Les interprètes visent la grande ligne ; le déroulé dramatique de la partition, avec ses alternances de véhémence et de confidence, I'emporte sur le relief contrapuntique. Pour I'esprit, pour I'humour évasif ou féroce, mieux vaut retourner à quelques versions d'élite – ca cogne plus d'une fois, et le scherzo de l'Opus 69 est carrément lourdaud ... L'énergie foisonnante du duo serait sans doute irrésistible dans la salle de concert, mais à I'épreuve du disque, elle avoue quelques limites.

A Tempo - Das Lebensmagazin | Juli 2018 | Sebastian Hoch | July 1, 2018 Alles ist hier anders

Der französische Cellist Marc Coppey, technisch glänzender Könner an seinem Instrument, ist nun gemeinsam mit seinem nicht minder virtuosen russischen Klavierpartner Peter Laul das Risiko eingegangen, das Gesamtwerk Beethovens für Violoncello und Klavier [...] als Livekonzert aufzunehmen. [...] Und dieses Risiko lohnte: Selten ist das ungewöhnliche und sonderbare, das befreiende und schöne der Cellowerke Ludwig van Beethovens überzeugender nachhörbar geworden [...].Mehr lesen

Infodad.com | June 28, 2018 | June 28, 2018 | source: http://transcent... Beethoven and Brahms: still surprising

Only musicians of the highest caliber would even be likely to attempt a survey of this sort on the basis of live recordings. That Coppey and Laul bring it off successfully is genuinely remarkable. The two play together with such solidity and refinement that it is often impossible to say which of them is taking the lead and who is taking the accompaniment role.Mehr lesen

Strings Magazine | June 15, 2018 | Laurence Vittes | June 15, 2018 | source: http://stringsma... Cellist Marc Coppey on Beethoven’s Works for Cello & Piano

Marc Coppey‘s superb new recording of Beethoven’s five sonatas and three sets of variations for cello and piano (Audite) with Peter Laul exploresMehr lesen

The two sets of Magic Flute variations actually sound like an homage to Mozart, while the concluding Fugue for the last Sonata has a serenity and resignation of command that suggests Prospero. Despite having played the music for 20 years, Coppey and Laul make seemingly spontaneous discoveries and show this with communicative awareness of a narrative that makes live performances so special.

Playing his 1711 Goffriller, using a modern French bow, a mix of gut and metal strings, and the blue Henle edition of the score, Coppey finds a magical, illuminating groove that perfectly integrates the hip and the modern.

Coppey opted for the Small Hall of the St. Petersburg Philharmonia, where the premieres of Haydn’s Creation (1802) and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis (1824) took place. The hall’s resident Steinway and the recording equipment from the former Melodiya studios completed the Saint Petersburg ensemble.

I spoke to Marc just before his annual chamber music festival in Colmar, France.

Does Beethoven’s music for cello also separate out in three periods, like the quartets and piano sonatas?

I think so. In the first two sonatas he is not as daring and the balance is very much in favor of the cello. The third one, however, has the kind of perfect balance that other major middle-period Beethoven has, like the Razumovsky Quartets and the Violin Concerto. He uses both instruments with absolute freedom and it’s total cello—with an incredible balance between their expressive capacities and tonal qualities.

And the last two sonatas, Op. 102, must be the late period.

The last two sonatas are what make it a unique set. Of course they’re smaller than the late quartets, but only the quartets, the piano sonatas, and the cello sonatas have these three major phases. And in this last phase for the cello sonatas it’s about anything you can imagine that can happen between two instruments.

Such as?

Such as the absurd fugue between two manifestly unequal fugue partners in the last movement of the last sonata. And to think that it comes after the only really slow movement in the whole set. But even though it’s a joyful, jubilant fugue, Beethoven still embraces within it the tender feelings associated with his close friend and its dedicatee Countess Anna Marie Erdödy. The last sonata is also in the long tradition, from Bach to Schoenberg, of the opposition between D major and D minor representing death and transfiguration, or death and resurrection. This last sonata is part of that and closes the five sonatas in the most glorious way

How early did you begin playing Beethoven?

I started playing Beethoven when I was really young, ten or 11. My teacher came with the music to my lessons and read them with me. I had only been playing the cello for two years but I still have a vivid memory of hearing the music for the first time. You know, Beethoven wrote wonderfully for the cello because he knew everything there was to know about the instrument, and so I learned to love the cello.

Why are your Magic Flute variations so successful?

From his earliest years, Beethoven combined the different voices of the cello; in the Magic Flute variations it sounds like each variation was for a different person onstage. They are like little operas that define the modern cello being an instrument that is more than beauty and being close to the human voice. In these variations Beethoven is close to human voices plural, as if he were speaking to us through the cello. There is something in general about the quality of the cello which lends itself to storytelling because of the variety and the dramatic aspects of the sound.

You recorded in St. Petersburg because of the connection to the first performances of Beethoven’s works, many of which took place there during his lifetime.

And because of the great acoustics, and the wonderful audiences. You can really project in the hall’s powerful, generous acoustic—but it’s not too big either, it’s very well balanced. There were a few cellists and musicians at the performances; but mostly the general public. The hall was sold out. It’s like that in Russia; audiences there are really passionate.

You recorded over two nights.

It was a challenge, but we’d been playing the sonatas for 20 years, and felt we could handle it. We were also at a phase in our lives when we felt more into the risk of live concerts—and basically because playing Beethoven not on the edge is not being Beethovenian.

opushd.net - opus haute définition e-magazine | 05.06.2018 | Jean-Jacques Millo | June 5, 2018 | source: http://www.opush...

With exalting energy, spontaneity at each moment, and undeniable expressive fervor, Marc Coppey and Peter Laul give Beethoven’s music a true “face;” here it is at its most inventive, at its warmest, at its most authentic, one could say. The passion of these two artists is evident from beginning to end of these admirable scores, offering, sharing the most human character of a creator of genius. This is art in its universal dimension.Mehr lesen

Fono Forum | Juni 2018 | Ole Pflüger | June 1, 2018

Wenn ein markerschütternder Ton in ein ansonsten stilles Notenfeld kracht oder Brüllen unvermittelt zum Flüstern wird, haben Marc Coppey und PeterMehr lesen

F. F. dabei | Nr. 11/2018 26. Mai bis 8. Juni | May 26, 2018

Der Franzose Marc Coppey und sein St. Petersburger Klavierpartner Peter Laul musizieren voller Energie und Temperament. Mehr lesen

www.ResMusica.com | Le 15 mai 2018 | Maciej Chiżyński | May 15, 2018 | source: http://www.resmu...

Pour son troisième album chez le label Audite, Marc Coppey s’aventure àMehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 17/04/2018 | Remy Franck | April 17, 2018 | source: https://www.pizz... Fein differenzierter Beethoven

Nach den so konträren Einspielungen durch Friedrich Kleinhapl und Andreas Woyke sowie Jean-Guihen Queyras und Alexander Melnikov bietet dieseMehr lesen

Der französische Pianist Marc Coppey und der russische Pianist Peter Laul haben die acht Werke im Kleinen Saal der St. Petersburger Philharmonie aufgenommen.

Die beiden ersten Sonaten werden noch ungemein leicht und charmant gespielt, als erste Versuche Beethovens in einer Gattung, die er gewissermaßen erfand. Auch die Variationen profitieren von dieser Eleganz und dem damit verbundenen Charme.

Mit seinem warmen und edlen Celloton bleibt Coppey den Werken weder in ihren sensiblen Aussagen noch in ihrer Virtuosität etwas schuldig. Auffallend und durchaus wertvoll ist die Präsenz des Klaviers, das nicht als Begleiter in den Hintergrund gedrängt wird, sondern vollwertig mitgestaltet.

Die Sonate op. 69 und die zwei letzten Sonaten op. 102 verlangen mehr Gestaltungsmittel, und die halten die beiden Interpreten bereit. Sehr wirkungsvoll sind Coppeys feuriges Drauflosgehen ebenso wie sein zarter, oft sehr reflektiver Lyrismus oder sein behagliches Schnurren, kurz gesagt, die Fülle von verschiedenen Ausdrucksmitteln, die Beethoven zugutekommen. Doch auch Peter Laul verdient höchstes Lob. Er ist gestalterisch perfekt eingebunden und spielt so sehr mit Farben und Schattierungen, dass das Dialogieren mit dem Cellisten für den Zuhörer sehr attraktiv wird.

Fresh, bright and unmannered, well differentiated performances of Beethoven’s music for cello and piano. The recording is very well balanced, giving the piano a strong but obviously correct presence.

www.qobuz.com | 6. April 2018 | Sandra Zoor | April 6, 2018 | source: https://www.qobu... Marc Coppey & Peter Laul spielen Beethovens Werke für Violoncello und Klavier in der St. Petersburger Philharmonie

Der Franzose Marc Coppey und sein St. Petersburger Klavierpartner Peter Laul musizieren voller Energie und Temperament und verleihen den populären Variationen und gewichtigen Sonaten unbestechlichen, glitzernden Klang. Die technische Perfektion der Musiker ist auch in der Livesituation beeindruckend.Mehr lesen

Radio Coteaux | 01 Avril 2018 | April 1, 2018 | source: http://www.radio... BROADCAST

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

concerti - Das Konzert- und Opernmagazin | 27. Oktober 2017 | Johann Buddecke | October 27, 2017 | source: https://www.conc...

Eindrucksvoll interpretiert

ECHO Klassik 2017: Quartetto di Cremona

Völlig unbeschwert, aber mit einer gehörigen Portion italienischer Leidenschaft und dem leichten Lebensgefühl des „dolce vita“ musizieren die vier Streicher [...] mit ihrem, mal elegant-strahlendem, mal tiefgehendem, fast schon sprödem Quartettsound. [...] das Quartetto di Cremona durchdringt das Quartettwerk Beethovens auf eine beeindruckende Weise.Mehr lesen

Crescendo | Sonderedition ECHO KLASSIK, 06/2017 Oktober-November 2017 | October 1, 2017

Der ganze vielfältige Beethoven

Das Quartetto di Cremona legt mit der siebten Folge aller Beethoven-Quartette das Spannungsfeld von Wiener Klassik und neuer Klangwelt frei

Cristiano Gualco und Paolo Andreoli an den Geigen versprühen ungebremste Lebendigkeit, Giovanni Scaglione am Cello sorgt für die coole, ja zuweilen eiskalte Erdung, und Simone Gramaglia an der Viola ist so etwas wie das harmonische Bindeglied. [...] Mehr lesen

hifi & records | 4/2017 | Uwe Steiner | October 1, 2017

Im frühen G-dur-Quartett legen die Italiener mit sorgfältiger Artikulation den ganzen sprachlichen und formalen Witz dieser mehrfach gebrochenen Komposition und mit sanglicher Phrasierung ihre ganze Musikalität frei. Bewundernswert, wie transparent sich die vier Stimmen auch im dritten der Rasumowski-Quartette verzahnen. Im extremen, aber stimmig musizierten Tempo des Fugato-Finales bleibt einem angesichts des virtuosen Wechsels zwischen Staccato- und Legato-Passagen der Mund offen. Die Tontechnik erzielt eine ideale Mischung zwischen Direkt- und Raumklang und bildet die vier Streicher in aller natürlichen Schönheit atemberaubend getreu ab. Wieder eine große Empfehlung!Mehr lesen

concerti - Das Konzert- und Opernmagazin | Oktober 2017 | Maximilian Theiss | October 1, 2017

Kunst der Unterhaltung

ECHO KLASSIK: Weitere Preisträger

Kammermusikeinspielung (Musik bis 19. Jh. | Streicher)<br /> Kürzlich wurde der Zyklus mit Beethovens Streichquartetten vollendet, geehrt wird nun aberMehr lesen

Kürzlich wurde der Zyklus mit Beethovens Streichquartetten vollendet, geehrt wird nun aber die vorletzte Einspielung der Gesamtaufnahme.

Kürzlich wurde der Zyklus mit Beethovens Streichquartetten vollendet, geehrt wird nun aber

Crescendo | 27.09.2017 | September 27, 2017 | source: http://www.cresc...

ECHO KLASSIK 2017: Das Quartetto di Cremona

Das Quartetto die Cremona legt mit der siebten Folge aller Beethoven-Quartette das Spannungsfeld von Wiener Klassik und neuer Klangwelt frei

Vor 17 Jahren hat sich das Quartetto di Cremona gegründet, und was esMehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | September 2017 | Erik Levi | September 1, 2017

The Quartetto di Cremona's ongoing Beethoven cycle has particularly impressed me for its visceral excitement and pulsating energy. Technical demandsMehr lesen

Another strength is their consummate mastery of soft mysterious playing, experienced here to best advantage in the unexpectedly veiled sounds they conjure up just before the recapitulation to the first movement of Op. 18 No. 2, or in the harmonically radical slow introduction to Op. 59 No. 3, where they manage to stretch tension and uncertainty to almost breaking point before the exuberant release of an unequivocal C major tonality in the ensuing Allegro vivace.

Yet for all their undoubted qualities, these performances miss certain ingredients that are also central to Beethoven's musical make-up, in particular charm and humour. The outer movements of Op. 18 No. 2 are a good case in point. In the opening Allegro, for example, the Quartetto di Cremona convincingly projects the sudden explosive fortes, but the principal melodic lines seem somewhat devoid of grace and elegance. Likewise, for all its brilliance of execution, the performers underplay the sheer impudence with which Beethoven changes to distant keys in the skittish Finale. In general, therefore, the more expansive Op. 59 No. 3 is better suited to the Quartetto di Cremona's approach.

deropernfreund.de | 24.8.2017 | Egon Bezold | August 24, 2017 Edle kammermusikalische Kost

Welches Quartett kann es sich schon leisten am Mikrokosmos der Beethoven-Streichquartette vorüberzugehen? Die komplette Edition hat das Cremona TeamMehr lesen

Simone Gramaglia meldet sich in den Mittelstimmen zu Wort. Mit Klang und Kraft bedient Giovanni Scaglione den Cello-Part. Was die Vierertruppe auszeichnet ist die artikulationskräftig erfrischende Art wie der Quartett-Text verdeutlicht wird, ohne dass jemand auf den Gedanken käme allzu deutlich mit dem didaktischen Zeigefinger aufzuzeigen.

Voller Überraschungen steckt die Wiedergabe der frühen sechs Quartette aus op. 18, die aufgrund der stilistischen Problematik mit zu den vertracktesten des Quartett-Zyklus zählen. So flitzen die schnellen Sätze als Kabinettstücke in spieltechnischer Präzision vorüber. Flexibel reagiert die Viererformation auf die Stimmungsumschwünge. Schlüssige Tempi markieren den Pulsschlag einer glutvollen Wiedergabe. Da wird nicht nur der Geist Haydns und Mozarts geweckt, sondern auch der mittlere und späte Beethoven vorausgedacht. Den klingenden Beweis liefern die kurzangerissenen Akkorde aus dem c-Moll op. 18,4. Auch das heikle Quartett op.18,5 gerät zum spannungsgeladenen Akt für fein ziselierte, nervig rhythmisierte Quartettkunst.

Hohe interpretatorische Intelligenz charakterisiert die Wiedergabe der mittleren Werkgruppe op. 59. Als eminent schweres Prüfstück erweist sich für die Primgeige das e-Moll Nr. 2, das Günther Pichler, der Ex-Primarius des Alban Berg Quartetts, als vertrackter als den Solopart des Beethoven-Violinkonzerts charakterisiert hat. Und es stimmt alles: die Spieltechnik, die sensibel ausgeschriebenen Übergänge, auch die vibrierenden Sechzehntelpassagen, die in der sich verflüchtenden Atmosphäre zu Tage treten. Welch fein abgetönte Stimmung prägt das ruhig genommene, breit ausgespielte „Adagio con sentimento“, das vorbildlich ausgewogen im Ausdruck fasziniert. Atem nehmend die akrobatische Fuge aus dem dritten Quartett, die selbst für ein professionelles Team eine Hürde darstellt. Dass dieser Sturmlauf wohl zum radikalsten gehört, was in der Sektion „Perpetuum mobile“ geschrieben wurde, machen die Cremona Leute klangartistisch zur Hetzjagd nach Noten.

Zur klanglichen Delikatesse gerät das Finale des ersten Satzes aus dem „Harfenquartett“ op. 74. Unwirsch springt einen das f-Moll Quartett op. 95 ins Gesicht. Da wird der musikalische Trotz buchstäblich auf die Spitze getrieben. Der große Gipfelsturm auf die Monster der späten Quartette, wo sich Spiritualität und geistiger Anspruch auf faszinierende Weise durchdringen, beginnt mit dem Es-Dur Quartett op. 127. Organisch gelingt die Darstellung, nirgends wird der natürliche Strom der Musik unterbrochen. So gewinnt das endlos fließende durch subtiles Variationenwerk angereicherte Adagio troppo, molto cantabile durch Ausspielen der harmonischen Reibungen besonders an Leuchtkraft. Dieser ausladende Satz wird mit viel Innenspannung aufgeladen. Da ist ein Auseinanderbröckeln ausgeschlossen. Mit welcher Reaktionsfähigkeit das Team die Stimmungsumschwünge realisiert, macht Staunen. Zum Quartett-Komplex zählt auch die Große Fuge B-Dur op.133 – ein nachkomponierter Bestandteil, der 6. Satz der Originalversion des Quartetts op. 130. Zu bewundern ist auch im a-Moll op. 132 der wunderbar ausgespielte „Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenden an die Gottheit“. Energisch durchgeformt erscheint das Alla marchia des vierten Satzes und die fulminant hoch wirbelnde Final-Stretta.

Die suitenartig aneinander gereihten Abschnitte im cis-Moll Quartett op. 131, die Beethoven ja auf das Komplizierteste nahtlos miteinander verzahnte, stiften überzeugende Einheit. Da werden die durchsichtig gespielten Details, die liberal behandelte Sonate nie aus dem Auge verloren. Im ersten Allegro kommen die Akzente konturenscharf. Innere Ruhe verströmen die schier endlos sich hin dehnenden Variationen. Es gibt keine Stimmenkorrespondenz, keine rhythmische Spannung, kein dynamischen Ansatz, über die vom Vierer Team flüchtig hinweg gespielt worden wäre. Von bohrender Kraft und beispielhaftem Standvermögen kündet der Finalsatz.

Diese exemplarische Auslegung bannt die Tontechnik auf das Format „Souround Sound – spielbar auf CD und SACD Player“. Das kammermusikalische Profil öffnet reizvolle kompositorische Perspektiven, vermittelt einen tiefen Einblick in Beethovens kammermusikalische Meisterschaft. Schulbildend für die Cremona Gruppe ist der Deutsch-Österreichische klassisch geprägte Stil (in Bezug auf Werktreue, Form und Stil) wie von Hatto Beyerle vom Alban Berg Quartett und in Fortsetzung von Piero Farulli vom Quartetto Italiano gepflegt wurde. Hier verbinden sich ein leidenschaftlich-emotionaler Ansatz mit romantisch geprägten Elementen sowie italienischer klanglicher Ästhetik. Da verschmelzen Struktur, Ausdruck und Form zur glühenden inneren Leidenschaft.

Fanfare | June 2017 | Huntley Dent | June 1, 2017 | source: http://www.fanfa...

Reviewers live with the frustration of how to convey music verbally, a frustration underscored by the Quartetto di Cremona. This is Vol. 7 of itsMehr lesen

It was far from a simple topic to Gramaglia: “[Vibrato] is a matter of the performers’ taste but also of structure….In op. 59 no. 2 there are many sections in E minor that are very dark but not as dark as, for example, in the tonality of C minor. There are many extremes of violence, and it’s very important to bring brightness into the darkness.” Brightness is interpreted as calling for no vibrato in this case. Gramaglia goes on to talk about how expressivity doesn’t necessarily mean the use of vibrato; there is a wide range of bowing techniques as well as the contract point of the bow on the string that must be considered.

The interviewer is intrigued by the PR blurb for the same recording, which says, “Beethoven’s musical language is no longer balanced and ‘well seasoned’ like that of his contemporaries but is extreme in every respect—ruthless and with feeling, dramatically operatic, and full of contrapuntal finesse.” It’s very promising that so much analytical attention is being applied to middle-period Beethoven (I’ve barely skimmed the surface of the interview), and the resulting performance on this new recording of the “Razumovsky” Quartet No. 3 is original to the point of being peculiar. As much ingenuity is applied to the details of sonority as if we were hearing one of Bartók’s later quartets. In fact, I’ve never encountered Beethoven played in such a piercing, at times existential, hollow, despairing, and alienated manner. Delivering a moment of charm is almost a betrayal of the ethos the Quartetto di Cremona wants to convey.

Typically, a group that plays the drawn-out chords of the Introduzione without vibrato would be making a period performance gesture. Here, however, the effect is stark, a slash-and-burn that is unabashed. But then what to do when the main Allegro vivace, with its boisterous major-key exuberance, contradicts the opening? The same dilemma arises in the second movement, where a certain poised lightness is implied by the marking Andante con moto quasi allegretto. The Cremona rocks back and forth with a questioning pulse that’s neurotically moody. Once again it’s very effective, but the gentle strain that comes up in the violins isn’t remotely this eerie as Beethoven scores it.

One can point to many imaginative details—they crop up in practically every measure—and after a certain point the listener must either give in or rebel. I find myself strongly on the side of giving in and appreciating with fascination how a familiar work is suddenly made to sound new. The Cremonas have made the point in print that Beethoven’s mature quartets are highly intellectual and deserve this kind of intense scrutiny. The scherzo creeps in on cat’s paws and really does remind me of the lopsided Hungarian dance rhythms of Bartók. The most divisive movement is the finale, where the marking of Allegro molto is injected here with amphetamines, turning into a manic Presto that to me sounds breathless. In all fairness, however, the 5:46 timing isn’t radically faster than the Alban Berg Quartet’s 6:01 from that ensemble’s first Beethoven cycle (EMI/Warner).

The second quartet from the op. 18 set fulfills Monty Python’s “and now for something completely different.” The Hamlet-like mood of the Cremonas’ “Razumovsky” performance is discarded in favor of comic relief. Using a bright tone made brighter without vibrato, they take the first movement and extend its Haydnesque animation into Beethoven’s unbuttoned brio. The four members of the Quartetto di Cremona—Cristiano Gualco and Paolo Andreoli, violins, Simone Gramaglia, viola, and Giovanni Scaglione, cello—are carefree and confident no matter how fast the passagework is. Every movement of their op. 18/2 wears a smile, and the performance exults in its own playfulness. The ensemble’s tone changes in weight and color quite impressively to match the moment, although the general tendency is toward a contemporary lightness and even edginess.

In all, this is a disc that makes me want to hear all of the Cremonas’ Beethoven to date. In the Fanfare Archive I found only one review so far, Jerry Dubins’s of Vol. 2 from 2014, which pairs the Second “Razumovsky” with op. 127. He seconds my opinion that this is a group to get excited about. Bright, lifelike sound from Audite adds to the immediacy of the performances.

The Strad | May 2017 | Julian Haylock | May 1, 2017 | source: https://www.thes... THE STRAD RECOMMENDS

Recorded in a warm, open acoustic, the striking range of sonorities createdMehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 22/04/2017 | Guy Engels | April 22, 2017 | source: https://www.pizz... Grandioses Finale in Dur

Beethoven als Lebensbegleiter scheint das Motto des ‘Quartetto di Cremona’ zu sein. Ergänzend zu den fulminanten und feurigen Aufnahmen derMehr lesen

Fast hat man den Eindruck, dass die Beethovenschen Quartette zu einer Art Droge geworden sind, eine Musik, die die Cremoneser nicht mehr loslässt. Gerade diesen fesselnden Zustand übertragen sie auch auf ihre Zuhörer. Man sitzt gespannt vor der Stereo-Anlage und lässt sich von jeder Note, von jeder Artikulation, von jedem Zwischenton mitreißen.

Das galt für die bisherigen sechs CDs dieser großartigen Referenz-Einspielung, das gilt auch für die neueste Produktion mit den Quartetten op. 18/2 und op. 59/3. Dass diese Gesamteinspielung Referenzcharakter haben würde, war sehr früh abzusehen.

Es zeugt von höchster Musikalität, von höchstem musikalischen Einvernehmen, wenn man als Quartett über einen derart langen Zeitraum die gleiche Spannung, die gleiche Intensität, die gleiche Frische des Musizierens aufrechterhalten kann.

Auch diesmal steht ein frühes Werk einer reiferen Komposition gegenüber. Das Quartett in G-Dur klingt frisch, wie eine leichte Brise, kraftvoll, spritzig in den schnellen Sätzen, verinnerlicht im Adagio.

Das spätere, dritte ‘Rasumowski-Quartett’ ist in seiner Anlage reifer und kühner. Einmal mehr lässt sich das ‘Quartetto di Cremona’ von dieser Kühnheit Beethovens nicht einschüchtern. Es pariert sie mit forschem Impetus, intensiver Spannung und kammermusikalischer Virtuosität, wie sie selten zu hören ist.

Excitingly intense and deeply musical performances of Beethoven’s Quartets op. 18/2 and 59/3.

Eine andere Rezension gibt es hier:

https://www.pizzicato.lu/was-fur-ein-zyklus/

www.pizzicato.lu | 24/02/2017 | Uwe Krusch | February 24, 2017 | source: http://www.pizzi... Was für ein Zyklus!

Eigentlich reicht der Satz: Es geht weiter wie bisher. Die Reihe der Einspielungen der Beethoven-Quartette wird mit zwei Quartetten aus den beidenMehr lesen

Wiederum wird die überwältigende Behandlung der Musik deutlich. Hier haben nicht die Quartettmusiker ihren Meister gefunden, sondern sie sind die Meister der Musik.

Ins Ohr fällt sofort der leichtere Ansatz, den man wohl mit italienischer Leichtigkeit bezeichnen könnte. Damit gelingt es den Cremonensern, den Werken eine Brillanz und Frische mitzugeben, die manch anderer Interpretation fehlt, möglicherweise, weil sich da der hinterhermarschierende Riese im Hinterkopf festgesetzt hat.

So erreichen die vier beispielsweise im Finalsatz des dritten Rasumovsky Quartetts eine schlicht umwerfende Rasanz, die aber den Eindruck spielerischer Leichtigkeit geradezu noch steigert, da das Spiel zwar umwerfend schnell klingt, gleichzeitig aber entspannt. Es bleibt der Eindruck, dass da Reserven vorhanden wären, während andere hier doch hechelnd ins Ziel kommen.

Two more of Beethoven’s string quartets provide decisive proof of Quartetto di Cremona’s overwhelming technical capacity and fantastic musicianship.

www.classicalcdreview.com | February 2017 | R.E.B. | February 1, 2017 | source: http://www.class...

This site has praised previous issues in the series, and those high standards continue here [...] the engineers have captured a very realistic audio picture.Mehr lesen

Gramophone | Gramophone Awards | Geoffrey Norris | October 1, 2013 Emerging triumphant from the flames

It was shunned at its premiere but Beethoven's Fourth Piano Concerto – wildly radical for its time – is now championed by countless performers.Mehr lesen

It's a chilly December evening in Vienna. A good-sized audience has braved the cold and gathered in the unheated Theater an der Wien for a marathon benefit concert featuring the radical composer whom everyone is talking about. He's a bit of an odd ball – often irascible, not a great socialiser, inclined to put people's backs up – but a lot of the music he writes is worth hearing, and he can be relied upon to come up with a surprise or two. Tonight the man himself is going to appear as soloist in his latest piano concerto and, it's rumoured, will do some improvisation in a new piece called Choral Fantasy, which he has knocked together in a hurry because he suddenly realised that a chorus was already on hand to sing parts of his Mass in C. There are to be premieres of two symphonies – his Fifth and Sixth – and a young soprano is standing in at the last moment to sing the scena and aria Ah! Perfido, the composer apparently having had a row with the diva originally booked.

The year was 1808. Beethoven sat down at the keyboard for his Fourth Piano Concerto, which he had already played the previous year at the palace of his well-disposed patron Prince Franz Joseph Maximilian von Lobkowitz. But this was the first time it had been heard by the paying Vienna public. All heads turned towards the conductor for a sign that he was going to give a downbeat for the orchestral introduction. That, after all, was the norm in a concerto in that day and age, but the composer played a quiet G major chord followed by a little questioning phrase, and it was only then that the orchestra came in. What was going on? Back in the 1770s, Mozart had done something similarly unexpected in the Concerto in E flat, K271, but even there the orchestra had the first say. More to the point, the new concerto was not riveting or dynamic: it was more as if the composer were poetically communing with himself. Minds wandered. The public were accustomed to sitting through long concerts, but the four hours and more of this one were taking things a bit far. The audience eventually trooped out of the theatre into the bitter Vienna night, frozen to the marrow and feeling short-changed.

As if that weren’t enough…

The uncomprehending reception of the Fourth Piano Concerto was just one of the misfortunes to beset this all-Beethoven night on December 22, 1808: the orchestra, ill-rehearsed and annoyed with Beethoven over some earlier misdemeanour, fell apart in the Choral Fantasy and the piece had to be started again. And far from being a benefit night for Beethoven, it is thought that he hardly managed to break even. The G major Concerto never really entered the core repertoire until Mendelssohn – that youthfully perceptive and vigorous campaigner on behalf of unjustly neglected causes, Bach included – rescued it in the 1830s. Clara Schumann took it up in the 1840s. In the 1860s Hans von Billow played it. Anton Rubinstein played it. Liszt admired it. The Fourth gradually overcame its unpromising entry into the world – as such ground breaking and unusual music is so often prone to do – and entered the canon of Beethoven's regularly performed concertos. These days its reception is immeasurably more favourable than that which its first audience was prepared or equipped to give it, and there is no shortage of recordings in the current catalogue. From a long list, I have selected for this comparative review 20 versions that represent some of the great names of the past and a cross-section of the young and seasoned artists of today.

From the earlier era there are Artur Schnabel (recorded 1933), Willhelm Backhaus (1950), Claudio Arrau (1957), Emil Gilels (1957), Wilhelm Kempff (1961), Daniel Adni (1971) and Clifford Curzon (1977). From more recent times, Maurizio Pollini (1992, as well as 1976), Alfred Brendel (1997), Pierre-Laurent Aimard (2002), Daniel Barenboim (2007, plus 1967), Evgeny Kissin (2007), Lang Lang (2007), Till Fellner (2008), Paul Lewis (2009) and Yevgeny Sudbin (2009). In a special category, Arthur Schoonderwoerd (2004) plays a period Johann Fritz piano; and on a modern Steinway Ronald Brautigam (2007) adopts Beethoven's revisions as published by Barry Cooper in 1994.

The matter of time

There is a whole world of difference here between, at the one extreme, the versions by Claudio Arrau, Daniel Adni and the earlier of Daniel Barenboim's two (all of them conducted by Otto Klemperer) and, at the other end, Brautigam's performance with the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra under Andrew Parrott. Whereas Klemperer exploits the full sumptuousness of the (New) Philharmonia Orchestra and takes about 20 minutes to negotiate the first movement, Parrott adopts 'period aware' thinking and sharper pacing with scant vibrato, and clocks up a running time of about 17 minutes for the first movement. That is about the norm in most of the recordings apart from Klemperer's, and, eminent though his performances are, the music does exude an air of lingering in a way that would certainly not have appealed to that first Vienna audience in 1808. Pierre-Laurent Almard with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe under Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Lang Lang with the Orchestre de Paris under Christoph Eschenbach and Evgeny Kissin with the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Colin Davis all demonstrate a slowness in this first movement – but it doesn't necessarily lead to languor. At times, however, it's a close-run thing, and in other versions the music certainly has more of a lift and a natural flow. Daniel Barenboim, conducting the Staatskapelle Berlin from the keyboard, shaves off just over a minute from the time he took under Klemperer, and the result is a performance that has power, concentration and crucial momentum.

Ronald Brautigam's pacing comes in at about the average, and his recourse to Beethoven's revisions is an interesting facet of his polished and discreetly shaped interpretation: the addition of more florid passages and extra notes and some chopping and changing of register lend the concerto a different perspective – more decorative and, in Cooper's words, 'strikingly inventive and more sparkling, virtuosic and sophisticated than the standard one'. Since these revisions are in Beethoven's own hand on the copyist's orchestral score, it is likely that he himself played it in much this way at the 1808 concert, though other artists have not yet followed his or Brautigam's example, at least on disc.

Going the whole hog in speculative performance practice, Arthur Schoonderwoerd on his fortepiano of 1805-10 actually comes in as the quickest exponent of the first movement by the stopwatch, but curiously he also sounds the most effortful, and those wiry, nasal old instruments in the reduced orchestral ensemble of Cristofori are very much an acquired taste.

If it is probably wise to eliminate Klemperer's three recordings from the final reckoning in terms of repeated listening, Artur Schnabel's 1933 performance is testament both to his brilliant artistry and to his characterful interpretative style. The remastered sound is not at all bad, and the relationship with the London Philharmonic Orchestra under (the not then Sir) Malcolm Sargent is secure and spontaneous. One might baulk at the slight ratcheting up of tempo when the piano re-enters at bar 74 of the first movement: Sargent faithfully adheres to the speed that Schnabel suggests during his opening phrase, but Schnabel then decides that he wants things to go a bit quicker after the long orchestral tutti. There are also some orchestral glissandi that speak of the practice at the time when this recording was made, but they do not unduly obtrude and the performance is one of infectious spirit, even if the finale does sometimes threaten to break free of its leash. Of the other 'historical' performances, Wilhelm Backhaus's with the RIAS Symphony Orchestra under Karl Böhm is of an impressive seriousness and eloquence of expression. The Fourth, recorded live in Berlin, was a favourite concerto of Backhaus, one in which he manifested his reputation as a 'devotedly unselfish mouthpiece' for the composers he was playing. This by no means implies a lack of imagination, for Backhaus's performance is one that combines serenity and vitality and also conveys a sure grasp of the concerto's structure. So, too, do Alfred Brendel and the Vienna Philharmonic under Simon Rattle, and Maurizio Pollini in characteristically translucent yet powerful fashion with the Berlin Philharmonic under Claudio Abbado and earlier on with the Vienna Philharmonic under Böhm. From more recent times, there are similarly well-reasoned performances from Till Fellner with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra under Kent Nagano, Paul Lewis with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Jirí Belohlávek and Yevgeny Sudbin with the Minnesota Orchestra under Osmo Vänskä. I cannot pretend that comparisons between any of these make the choice of a preferred version any easier: all of them have searching qualities and interpretative personalities that seem to be in harmony with the music's disposition.

The cadenza issue

Alfred Brendel's performance does, however, raise the interesting question of the cadenzas. Beethoven wrote two for the first movement and one for the last. Many other composers and pianists have supplied their own over the years, including Brahms, Busoni, Godowsky, Saint-Saens and Clara Schumann. Wilhelm Kempff preferred to use his own cadenzas for his recording with the Berlin Philharmonic under Ferdinand Leitner, as does Arthur Schoonderwoerd with Cristofori. Other pianists are divided, if not equally, between Beethoven's two first-movement cadenzas. The one most commonly favoured begins in 6/8 with a quickened-up version of the opening theme in repeated Gs in the right hand. The other, starting with soft octave Gs in the left hand, builds to a swift climax and a torrent of descending thirds. Alfred Brendel and Maurizio Pollini are among the proponents of this more ominous, wilder – if shorter – cadenza, and in his book Music Sounded Out (1995, page 57) Brendel gives his reasons. 'May I assure all doubting Thomases', he says, 'that the cadenza I play in the first movement of the Fourth Concerto is indeed Beethoven's own; the autograph has the superscription Cadenza ma senza cadere ['Cadenza, but without falling down'] ' an allusion to its pianistic pitfalls. I have often been asked why I should waste my time on this bizarre piece when another more lyrical, and plausible, cadenza is available. I think that the [superscription) adds something to our knowledge of Beethoven. It shows almost shockingly how Beethoven the architect could turn, in some of his cadenzas, into a genius running amok. Almost all the classical principles of order fall by the wayside, as comparison with Mozart's cadenzas will amply demonstrate. Breaking away from the style and character of the movement does not bother Beethoven at all, and harmonic detours cannot be daring enough. No other composer has ever offered cadenzas of such provoking madness.' If someone else had written this weird cadenza, he or she would surely have been roundly condemned for shattering the mood of the first movement, but, as it is, it is there as an entirely justifiable option. Brendel's performance of it certainly underlines his point about Beethoven's genius running amok, and the cadenza delivers a similar blow to the senses in the two recordings by Maurizio Pollini. If the choice of the first-movement cadenza is a major factor in your enjoyment of the Fourth Concerto, then this needs to be taken into account. Backhaus, incidentally, plays the 'usual' Beethoven cadenza in the first movement, but his own stormy, bravura one in the finale.

There is one recording that has not so far been mentioned. In an effort to keep up the suspense about the ultimate choice in this Fourth Piano Concerto (though the boxes scattered about this review will already have given more than a clue), I have not yet put forward the name of Emil Gilels. Strictly speaking, his recording comes in the historical category, since it was made in 1957 with the Philharmonia Orchestra under Leopold Ludwig, but its sound is exceptionally well remastered and it is a performance of transcendent beauty allied to power, delicacy, control and a palette of colour – both in the piano and in the orchestra – that is second to none. Gilels was in his maturity when he made this sublime recording (coupled with the Fifth Concerto) at the age of 41, and it testifies to the stylistic understanding and thoughtful qualities that distinguished his piano-playing at its best. The first movement is eloquently voiced – 'poetry and virtuosity are held in perfect poise', as a Gramophone review rightly put it; and he gives a vibrant account of the wilder first-movement cadenza that Brendel and Pollini also prefer.

Pinning all one’s hopes on the slow movement

When it comes to the short slow movement, the dialogue between the aggressive orchestra and the ameliorating piano is judged immaculately and poignantly by Ludwig and Gilels.It was the critic Adolf Bernhard Marx who (in 1859) propounded the theory that this movement could be viewed as an analogy of Orpheus pacifying the Furies at the gates of Hades, a romantic notion that has held sway ever since. Whatever was in Ludwig's and Gilels's minds, the orchestra's gradual acquiescence under the piano's gently persuasive influence is pure magic. By contrast, on Clifford Curzon's recording with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra under Rafael Kubelik – a performance that is otherwise of great distinction – the orchestra sounds merely a bit blunt rather than hostile. Nagano has his Montreal Symphony Orchestra tripping lightly on Fellner's recording; Böhm sounds ominous, if a little ponderous, for Backhaus, though Backhaus's own playing is melting. Leitner gives something appropriately stern for Kempff to answer on his recording. Sargent's crisp note values observe the sempre staccato marking at the start of the slow movement and thus give the music more bite for Schnabel. Belohlávek and Lewis also manage this discourse effectively, as do Rattle and Brendel. It is debatable whether either Abbado or Böhm on Pollini's recordings makes adequate distinction between the two parties in the same, almost visually palpable, way that Ludwig and Gilels do, and on Sudbin's otherwise first-rate recording Vänskä coaxes a surprisingly soft-edged attack from the Minnesota Orchestra at this juncture.

It is odd, perhaps, that after barely being able to put a pin between a good many of the available recordings of the Fourth Concerto, so much should hinge on how the orchestra reacts to the piano in the slow movement, and vice versa. The finales do not disappoint in any of the leading versions, but with the slow movement proving to be, if subjectively, a point where some performances are more clearly defined in impact than others, the final choice would seem to rest on five versions: Backhaus and Böhm with the RIAS Symphony Orchestra from 1950, Gilels with the Philharmonia Orchestra under Ludwig from 1957, Kempff with the Berlin Philharmonic and Leitner from 1961, Brendel and Rattle with the Vienna Philharmonic from 1997 and Lewis with Belohlávek and the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 2009. In addition, there is an irresistible élan to Schnabel's 1933 performance with the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Sargent, and much of textural and interpretative interest in the 2007 version by Brautigam and the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra under Parrott.

The last of these, being the only one to adopt Beethoven's manuscript revisions to the concerto, comes across with a different sort of scintillating zest that is particularly attractive, and the disc (with the piano arrangement of the Violin Concerto as coupling) could be a refreshing addition for anybody wanting a companion to a recording of the received version. Schnabel, Backhaus and Kempff in their different ways bring timeless musicianship to their interpretations, but the mix of vitality and visionary expressiveness in the Backhaus just gives that one the edge – remembering, though, that he plays his own cadenza in the finale. With the recording by Brendel and Rattle (Brendel's third recording of the Fourth Concerto, the others being with Bernard Haitink and James Levine) there is a true meeting of musical minds, the orchestra and piano establishing a mutual understanding of their roles in the expressive and dynamic scheme of things. The interpretative bond between Lewis and Belohlávek is similarly a close and fertile one and has forged not only a compelling performance of the Fourth Concerto but also a complete set of all five. But when it comes down to it, the special qualities of Gilels – his poetry, power and poise – put him prominently in prime place.

ouverture Das Klassik-Blog | Samstag, 4. August 2012 | August 4, 2012

Dem Andenken eines großartigen Sängers gewidmet ist die EditionMehr lesen

Crescendo Magazine | mise à jour le 18 novembre 2010 | Bernard Postiau | November 18, 2010

Contrairement au disque Strauss que nous avons reçu parallèlement àMehr lesen

www.ResMusica.com | 03/11/2010 | Patrick Georges Montaigu | November 3, 2010 Beethoven Böhm Backhaus : du grand classique, mais pas très nouveau

Puisant dans la riche réserve d’enregistrements réalisés à partir desMehr lesen

American Record Guide | July-August 2010 | William Bender | July 1, 2010