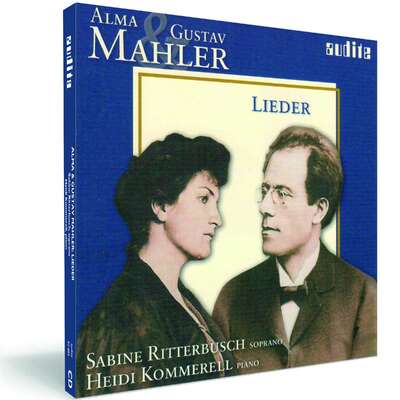

"Now just imagine a work so grand that it actually reflects the entire world... All of nature receives a voice in it, and it tells such deep secrets that one possibly imagines oneself to be dreaming." (Gustav Mahler in a letter to Anna von Mildenburg, Summer 1896) Gustav Mahler's conception...more

"Ein charakteristischer Ausschnitt für das Mahler-Bild von Rafael Kubelk: beredt, frisch, voller Liebe zum Detail, das er mit äußerster Genauigkeit ausformt. ...Sein Klang ist in jedem Augenblick transparent, ja ungewöhnlich hell, ... Unter seinen Händen entsteht ein filigranes Netz, ein in sich bewegtes Spiel von Linien, die auf wundersame Weise, miteinander verbunden zu sein scheinen." (SWR)

Track List

Details

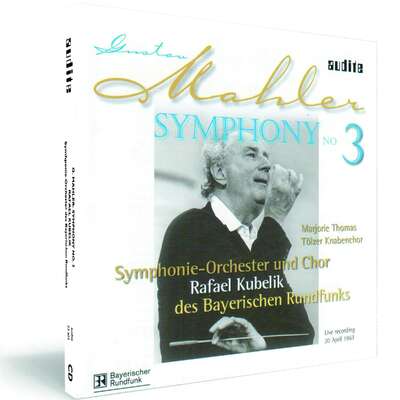

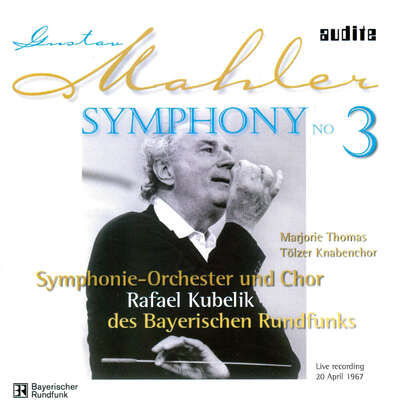

| Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 | |

| article number: | 23.403 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4009410234032 |

| price group: | BCA |

| release date: | 1. January 2001 |

| total time: | 94 min. |

Informationen

"Now just imagine a work so grand that it actually reflects the entire world... All of nature receives a voice in it, and it tells such deep secrets that one possibly imagines oneself to be dreaming." (Gustav Mahler in a letter to Anna von Mildenburg, Summer 1896)

Gustav Mahler's conception whilst composing his Third Symphony was nothing less than the embedding of man in nature as the all-embracing cosmic power - the Third Symphony, with which the meanwhile renowned audite series of Mahler Symphonies with Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra is being continued. The Third has the reputation of being problematical - not because of any lack of quality, but because a contradiction exists between the claim made for the work described above and the completed work itself. Mahler gave each movement a motto, later not published, seizing upon certain natural phenomena (Pan Awakens, What the Flowers on the Meadow Told Me, etc.) However, the musical realisation reveals the (for him) so typical gap between almost naive joy of living and plunges into the deepest of despair - the unbroken representation of nature as a security-giving power cannot succeed and is, in its hopeless failure, a shockingly visionary anticipation of the catastrophes of the coming twentieth century. The work appears in a live recording made in the Hercules Hall of the Munich Residenz on 20 April 1967.Reviews

Diapason | Avril 2007 | Christian Merlin | April 1, 2007 Gustav Mahler : La symphonie n° 3

Mois après mois, toutes les clés pour comprendre les chefs-d'oeuvre du répertoire : histoire, enjeux, guide d'écoute et repèresMehr lesen

[...]

Plus que de simples outsiders, deux Tchèques ont su retrouver les racines bohémiennes de Mahler : Kubelik, dont le live lyrique et véhément (Audite) est bien préférable à la version de studio, exactement contemporaine (DG), et le trop oublie Vaclav Neumann [...].

www.new-classics.co.uk | January 2005 | January 1, 2005

The renowned Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Women’s Chorus, conducted by the great Rafael Kubelik, perform one of Gustav Mahler’sMehr lesen

CD Compact | n°174 (marzo 2004) | Francisco Javier Aguirre | March 1, 2004 Audite/Rafael Kubelik

El intenso patriota que fue este director checo, celebró el regreso a suMehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | February 2004 | Tony Duggan | February 1, 2004

The last time I reviewed a recording of Mahler’s Third Symphony I stated again my belief that in this work above all of Mahler’s we must look to aMehr lesen

It takes a particular kind of conductor to turn in a great Mahler Third. No place for the tentative, or the sophisticated, particularly in the first movement which will dominate how the rest of the symphony comes to sound no matter how good the rest is. No place for apologies in that first movement especially. No conductor should underplay the full implications of this music’s ugliness for fear of offending sensibilities. The lighter and lyrical passages will largely take care of themselves. It’s the "dirty end" of the music - low brass and percussion, shrieking woodwinds, growling basses, flatulent trombone solos - that the conductor must really immerse himself in. A regrettable trait of musical "political correctness" seems to have crept into more recent performances and recordings and that is to be deplored. If you want an example of this listen to Andrew Litton’s ever-so-polite Dallas recording. There is much to admire in some recent recordings by Tilson Thomas, Abbado and Rattle to name just three from recent digital years. However they don’t approach their older colleagues in laying bare the full implications of the unique sound-world Mahler created in the way that I think it should be heard. The edges need to be sharp, the drama challenging, Mahler’s gestalt shrieking, marching, surging, seething and, at key moments, hitting the proverbial fan.

Rafael Kubelik’s superb DG recording had one drawback in that the recorded balance was, like the rest of his Munich studio cycle, rather close-miked and somewhat lacking in atmosphere. It never bothered me that much, as you can probably imagine, but just occasionally I felt the need for a little more space. As luck would have it, this Audite release in the series of "live" Mahler performances from Kubelik’s Munich years comes from the same week as that DG studio version and must have been the concert performance mounted to give the players the chance to perform the work prior to recording in the empty hall. It goes some way to addressing the problem of recorded balance in that there is a degree more space and atmosphere, more separation across the stereo arc especially. It thus offers an even more satisfying experience whilst still delivering Kubelik’s gripping and involving interpretation with the added tensions of "live" performance. There is a little background tape hiss but nothing that the true music lover need fear. So here is another "not originally for release" broadcast recording of Mahler’s Third for the list of top recommendations.

Like all great Mahler Thirds this reading has a fierce unity and a striking sense of purpose across the whole six movements, lifting it above so many versions that miss this crucial aspect among so many others. Tempi are faster than you may be used to. It also pays as much attention to the inner movements as it does the outer with playing of poetry, charm and that hard-to-pin-down aspect, wonderment. In the first movement Kubelik echoes Schoenberg’s belief that this is a struggle between good and evil, generating the real tension needed to mark this. Listen to the gathering together of all the threads for the central storms section, for example. Kubelik also comes close to Barbirolli’s raucous, unforgettable "grand day out up North" march spectacle and shares his British colleague’s (and Leonard Bernstein’s) sense of the sheer wackiness of it all. Listen to the wonderful Bavarian basses and cellos rocking the world with their uprushes and those raw, rude trombone solos, as black as an undertaker’s hat and about as delicate as a Bronx cheer or an East End Raspberry. Kubelik also manages to give the impression of the movement as a living organism, growling and purring in passages of repose particularly, fur bristling like a cat in a thunderstorm. Too often you have the feeling in this movement that conductors cannot get over how long it is and so they want to make it sound big by making it last for ever. In fact it is a superbly organised piece that benefits from the firm hand of a conductor prepared to "put a bit of stick about" and hurry it along like Kubelik.

In the second movement there is a superb mixture of nostalgia and repose with the spiky, tart aspects of nature juxtaposing the scents and the pastels. Only Horenstein surpasses in the rhythmic pointing of the following Scherzo but Kubelik comes close as his sense of purpose seems to extend the chain of events that was begun at the very start, still pulling us on in one great procession. The pressing tempi help in this but above all there is the innate feel for the whole picture that only a master Mahlerian can pull off and frequently only in "live" performance. Marjorie Thomas is an excellent soloist and the two choirs are everything you would wish for, though Barbirolli’s Manchester boys - all urban cheekiness straight off the terraces at Old Trafford or Main Road - are just wonderful. In the last movement no one offers a more convincing tempo than Kubelik, flowing and involving, never dragging or over-sentimentalised. Like Barbirolli, though warm of heart, he refuses to indulge the music and the movement wins out as the crowning climax is as satisfying as could be wished.

This is a firm recommendation for Mahler’s Third and another gem in Audite’s Kubelik releases.

Badische Zeitung | 18.11.2003 | Heinz W. Koch | November 18, 2003

... Wie spezifisch, ja wie radikal sich Gielens Mahler ausnimmt, erhellt schlagartig, wenn man Rafael Kubeliks dreieinhalb Jahrzehnte alte und vorMehr lesen

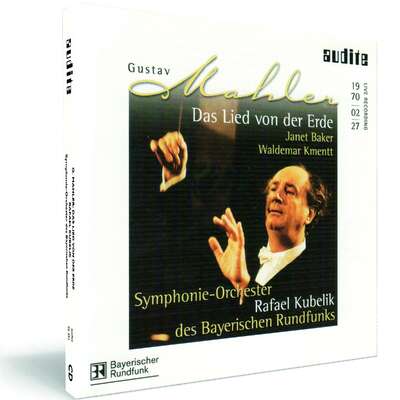

Eine gehörige Überraschung gab’s schon einmal – als nämlich die nie veröffentlichten Münchner Funk-„Meistersinger“ von 1967 plötzlich zu haben waren. Jetzt ist es Gustav Mahlers drei Jahre später eingespieltes „Lied von der Erde“, das erstmals über die Ladentische geht. Es gehört zu einer Mahler Gesamtaufnahme, die offenbar vor der rühmlich bekannten bei der Deutschen Grammophon entstand. Zumindest bei den hier behandelten Sinfonien Nr. 3 und Nr. 6 war das der Fall. Beim „Lied von der Erde“ offeriert das Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, dessen Chef Kubelik damals war, ein erstaunlich präsentes, erstaunlich aufgesplittertes Klangbild, das sowohl das Idyllisch-Graziöse hervorkehrt wie das Schwerblütig-Ausdrucksgesättigte mit großem liedsinfonischem Atem erfüllt – eine erstrangige Wiedergabe.

Auch die beiden 1967/68 erarbeiteten Sinfonien erweisen sich als bestechend durchhörbar. Vielleicht geht Kubelik eine Spur naiver vor als die beim Sezieren der Partitur schärfer verfahrenden Dirigenten wie Gielen, bricht sich, wo es geht, das ererbte böhmische Musikantentum zumindest für Momente Bahn. Da staunt einer eher vor Mahler, als dass er ihn zu zerlegen sucht. Wenn es eine Verwandtschaft gibt, dann ist es die zu Bernstein. Das Triumphale der „Dritten“, das Nostalgische an ihr wird nicht als Artefakt betrachtet, sondern „wie es ist“: Emotion zur Analyse. ...

(aus einer Besprechung mit den Mahler-Interpretationen Michael Gielens)

Scherzo | N° 175, Mayo 2003 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | May 1, 2003

Kubelik logra con su sabiduría e instinto una unidad y convicción queMehr lesen

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

klassik.com | 24.02.2003 | Erik Daumann | February 24, 2003 | source: http://magazin.k... Der Visionär

Gustav Mahler komponierte seine dritte Symphonie in den Sommermonaten derMehr lesen

Die Rheinpfalz | 12.02.2003 | Gerhard Tetzlaf | February 12, 2003 Idealer Interpret – Livemitschnitte unter Rafael Kubelik

Die Gesamtaufnahme der Sinfonien Gustav Mahlers durch Rafael Kubelik undMehr lesen

Westfalen-Blatt | Nr. 25/2003 | Ingo Schmitz | January 30, 2003

Eine schlichte schwarze Blechplatte ziert seit wenigen Tagen dasMehr lesen

International Record Review | 12/2002 | Graham Simpson | December 1, 2002

Despite the (necessary!) tailing off in complete cycles over the last decade, recordings of Mahler symphonies are far from drying up. Rafael KubelíkMehr lesen

As with his live Sixth Symphony (reviewed in June 2002), Kubelík's live Third is contemporary with his studio account still among the most spontaneous on disc. Similar virtues are in evidence here, though some will question the rushed ascents to the Kräftig's climactic peaks (listen from 11'51" and 27'00"), which undermine an otherwise fluid, coherent approach to this too-often sprawling movement. The Menuetto's coda (8'26") is winsome, while the posthorn interludes of the Comodo (5'32" and 12'51") have a repose to contrast with the fantasy that Kubelík captures elsewhere. Marjorie Thomas is thoughtful rather than profound in the Nietzsche setting, and the balance of boys' and women's voices in the Wunderhorn movement lacks definition. Kubelík again rushes his fences in the finale's central climax (13'42"), but there's no doubting his overall command of form and expression. String playing is assured throughout, though wind intonation in the closing pages (21'09") is raw to say the least.

This is something that could not be levelled at any stage of Claudio Abbado's live traversal: indeed, the fastidious balance and clarity of texture are remarkable even by his standards. An emotional detachment is evident in the opening movement notably the central development (15'46"), where Abbado evinces little of the character or imagination of Kubelík. After a powerfully sustained reprise (23'42"), the coda is curiously stolid, lacking the joyful discharge of energy essential at this point. The Menuetto, pellucid in tone and manner, is perfectly judged; the Comodo lacking in an imaginative dimension, and with a posthorn balance (listen from 5'21") so distant as to be more a timbral shading than a melodic contour. Abbado's way with the Nietzsche setting a tensile arioso, with Anna Larsson ideally poised between agitation and restraint is spellbinding, as is the glinting aggression drawn from the orchestral passage after the Wunderhorn movement's central section (2'16"). In the finale, the inner intensity of the Berlin Philharmonic's playing, and the unerring pacing across its 22-minute span secure an apotheosis that eluded Abbado in his disappointingly bland Vienna account. The audience is suitably impressed, though to retain three minutes of applause on disc does seem excessive.

The sound on the Audite release is decent and not too scrawny, and there are inscrutable booklet notes from Erich Mauermann: worth hearing, though Kubelík's studio account should be made available as a competitive 'twofer'. The DG engineers have worked hard to open up the notoriously cramped Royal Festival Hall acoustic and if the results convey little sense of a specific acoustic, balance of ensemble in a believable ambience makes for a sympathetic listen, enhanced by comprehensive notes from Donald Mitchell. This is a recording which can rank high, if not quite with the best, of those listed.

Fanfare | November/December 2002 | Christopher Abbot | November 1, 2002

Like Audite’s disc of Kubelik’s Mahler Sixth (reviewed in 25:5), this recording was made at a concert that preceded the studio recording ofMehr lesen

Kubelik’s performances of the “massive” Mahler—the Second, Third, and Eighth—were less purely monumental than either Solti or Bernstein, his contemporaries in the early Mahler-cycle stakes. Kubelik often celebrates the smaller, finer gestures, so the sense of struggle between elemental forces in the first movement of the Third isn’t as pronounced as it is with the other two, especially Bernstein. Unfortunately, the sound on this new disc makes less of an impact than that on DG: The orchestra is recessed, so that the imperious horn calls and march are less so. Orchestral detailing is notable, but there are several rough patches where intonation is less than secure. There are occasions in the development where the tempo seems rushed—the sense of momentum isn’t organic. This is less of a problem on the DG recording.

Not surprisingly, the minuet is exquisite on the DG. It is no less so on the Audite, where the stereo image is just as sharp (though tape hiss is a distraction). The sound on Audite is somewhat thin, adding a metallic sheen to the winds. The playful Scherzo is also delightful, full of the small gestures I alluded to, such as the perfectly judged post horn solos. Marjorie Thomas contributes an “O Mensch!” that is fully characterized, though her voice seems to emerge from an echo chamber; the balance between choruses on “Es sungen drei Engel” is also problematic, with the women dominating the boys. Kubelik’s employment of divided violins makes the all-important string writing extra clear in the final Adagio. His is an interpretation not without emotion, but with an overall sense of balance that works extremely well.

As with the previous Audite Mahler/Kubelik, this disc is primarily of historic value, vital for those who don’t already own the DG set. It is an interpretation worth hearing, with the caveats concerning the sound as noted above.

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Le Monde de la Musique | Juillet - Août 2002 | Patrick Szersnovicz | July 1, 2002

L’immense Troisième Symphonie (1895-1896), vision panthéiste embrassant toute la nature, depuis les fleurs, les animaux jusqu’aux êtresMehr lesen

Comme dans de remarquable Cinquième, Sixième et Neuvième Symphonies et de splendides Première (« Choc »), Deuxième (idem) et Septième précédemment parues, Rafael Kubelik dans ce cycle de concerts inédits Mahler/Radio bavaroise se montre plus libre, plus fascinant que dans sa version de studio « officielle », un rien trop rapide et burinée, réalisée pourtant à la même époque (DG, 1966). Les tempos sont assez vifs, comparativement aux enregistrements de référence signés par Horenstein, Bernstein, Haitink, et Kubelik privilégie l’absence de pathos, le dépouillement, l’économie des contrastes, des gradations dynamiques et la mise en valeur da la complexité polyphonique. L’immense premier mouvement, d’une exaltation progressive, bénéficie de couleurs fauves et d’une articulation subtile. Les mouvements médians offrent un climat davantage mystérieux et rêveur, mais le finale, évitant lui aussi toute lourdeur, séduit plus par la tension que par sa ferveur.

Répertoire | Juin 2002 - N° 158 | Jean-Marie Brohm | June 1, 2002

Après les Symphonies Nos 1, 2, 5, 7 et 9, Audite poursuit la publicationMehr lesen

Hi Fi Review | Vol. 192, May/June 2002 | May 1, 2002

chinesische Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

Neue Musikzeitung | 5/2002 | Reinhard Schulz | May 1, 2002

Dass man Kubeliks Mahler-Zyklus auf CD neu veröffentlicht, kann man nurMehr lesen

Fono Forum | 4/2002 | Christian Wildhagen | April 1, 2002 Sogkraft

Von Rafael Kubelíks Studio-Zyklus aller Mahler-Sinfonien hieß es oft, er betone die böhmische Seite der Musik – ein allzu billigesMehr lesen

Offenkundig handelt es sich bei den Sinfonien Nr. 3 und Nr. 6 um Aufzeichnungen der Konzerte, die den DG-Aufnahmen vorangingen. Man erlebt alle Höhen und Tiefen von Live-Produktionen: kleinere Patzer und eine im Eifer des Gefechts mitunter nivellierte Dynamik, dafür aber mitreißende Spannungsbögen und eine Natürlichkeit der vorwärts drängenden Agogik, die ihresgleichen sucht. So gehört die „Feurig“ überschriebene Passage im Finale der Sechsten (ab 12’58’’) zu den atemberaubendsten Beispielen eines virtuos-enthemmten Orchesterspiels. Eine fast fatalistische Sogkraft scheint die Musik in ihren Strudel zu ziehen, auch im Andante gönnt Kubelík dem Hörer keine Oase der Entrückung.

Ausgeglichener und überragend in seiner großräumigen Disposition wirkt der Mitschnitt der Dritten, der in jedem Moment von der Persönlichkeit des Dirigenten durchdrungen scheint. Kaum ein Detail bleibt da unausgeleuchtet, und allenfalls das zu grobschlächtige Blech trübt bisweilen das Hochgefühl dieser beeindruckenden Aufführung.

Pizzicato | 03/2002 | Rémy Franck | March 1, 2002 Überraschungen mit Kubelik

Es ist doch erstaunlich, wie anders Kubelik Mahler live dirigiert, anders als die anderen Dirigenten, anders als er selbst in der Studioaufnahme. AuchMehr lesen

Darum: Eine essentielle Mahler-Deutung, die sich jedem, der sich ernsthaft mit Mahler auseinandersetzen will, geradezu aufdrängt.

Die Presse | Nr. 16.198 | Wilhelm Sinkovicz | February 15, 2002

Die Edition der Live-Mitschnitte der Münchner Mahler-Konzerte RafaelMehr lesen

www.ClassicsToday.com | 01.01.2002 | David Hurwitz | January 1, 2002

After slogging through Claudio Abbado's dismal, wretchedly recorded (live)Mehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | December 2001 | David Nice | December 1, 2001

There were improvements to be made on Abbado’s 1980 Vienna recording of Mahler 3, especially given dim timpani strokes and sour chording in theMehr lesen

SWR | 7. November 2001 | Norbert Meurs | November 7, 2001

(Hörprobe: CD 2, Track 2 – 2’30, bei 1’30 mit Text drüber)<br /> <br /> EinMehr lesen

Ein

www.buch.de | 15.10.2001 | Olaf Behrens | October 15, 2001

Für jeden Mahler - Liebhaber sind die Liveeinspielungen der Symphonien mitMehr lesen

Rondo | 6/2001 | Oliver Buslau | June 1, 2001

Lorbeer + Zitronen

Was Rondo-Kritikern 2001 besonders gefallen und missfallen hat

Meine stille Liebe:<br /> die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mitMehr lesen

die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mit

Süddeutsche Zeitung | 22.04.1967 | Karl Schumann | April 22, 1971

Rafael Kubelik besitzt das, was weder die flotteste Schlagtechnik noch derMehr lesen