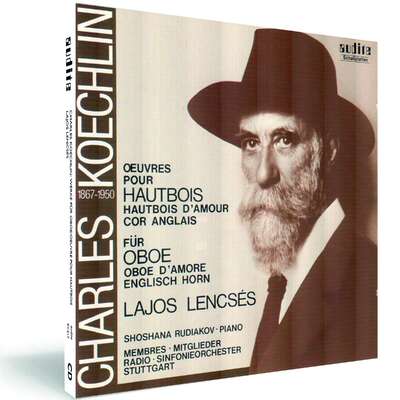

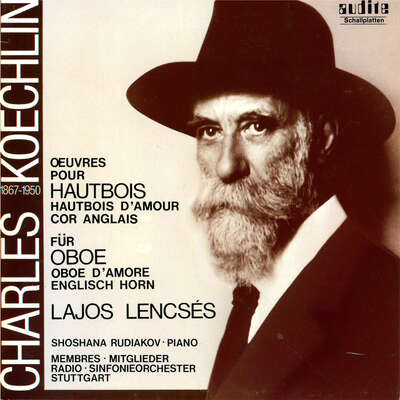

Charles Koechlin

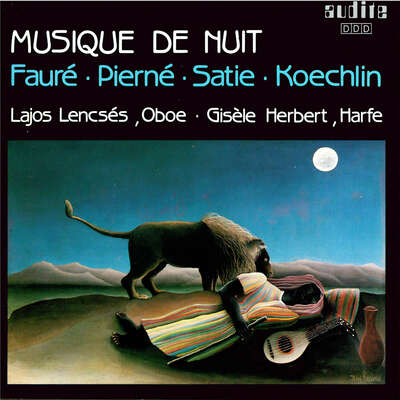

"Lajos Lencsés, Solo-Oboist des Radio-Sinfonieorchesters Stuttgart, verfügt über den entsprechend schlanken, flexiblen Ton und die musikalische Ausdruckskraft, um Koechlins Musik zum Klingen zu bringen." (Musikmarkt)

Details

| Charles Koechlin: Works for Oboe | |

| article number: | 97.417 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4009410974174 |

| price group: | BCA |

| release date: | 1. January 1990 |

| total time: | 50 min. |

Reviews

ABC – Blanco y negro Cultural | A. G. L. | March 6, 2004 KOECHLIN. Obras para oboe, oboe d'amore y corno inglés.

Poco y mal conocido, Charles Koechlin, además de teórico, es un buenMehr lesen

Aus urheberrechtlichen Gründen dürfen wir ihnen diese Rezension leider nicht zeigen!

Poco y mal conocido, Charles Koechlin, además de teórico, es un buen

Scherzo | N° 184, Marzo 2004 | S.M.B. | March 1, 2004

Sorprende que obras de la delicadeza, el sosiego y la inspiraciónMehr lesen

Aus urheberrechtlichen Gründen dürfen wir ihnen diese Rezension leider nicht zeigen!

Sorprende que obras de la delicadeza, el sosiego y la inspiración

Fanfare | Jan/Feb 1992 | Adrian Corleonis | January 1, 1992

Soon after the review of the above cited Audite disc appeared, a reader wrote privately to ask if the album number were correct—the distributorMehr lesen

Soon after the review of the above cited Audite disc appeared, a reader wrote privately to ask if the album number were correct—the distributor claimed it was "nonexistent." He was, apparently, entering the jungle for the first time. . . .

By chance, one hears something haunting. The composer may have been encountered in footnotes but had remained innocent of auditory associations. Small and not very representative pieces may be available as filler and one collects them, becoming more intrigued—as shelf space disappears beneath umpteen mediocre performances of the basic repertoire items one endures for the privilege. Reference books serve mainly to tantalize, the best of them with complete catalogs and tidings of large, rarely performed works marking grand syntheses. Descended from these, album copy tends to be a circus of undigested (mis-)information, dutifully parroted by reviewers to create an odd consensus about a body of music which only a very few people could know at first hand; though, occasionally (notably, on early LP jackets), gracefully revealing notes by uncelebrated, even anonymous, writers will prompt the ear and prime the spirit with a loving erudition surpassing anything in scholarly sources. Slowly, the picture fills in as stalking the elusive forgotten master becomes a passion. One searches old and foreign catalogs, canvasses out-of-print dealers, turns up antique vinyl and ancient monographs in languages in which one is not fluent, and scarce, expensive sheet music which remains impervious to the assaults of one's musicianship. The large, epochal works receive once-in-a-decade (or two, or three) performances and circulate on tape, pirate recordings, or short-lived commercial issues. Reputations shift a bit as dissertation topics thin, and the picture takes on overwhelming, highly specific detail. One is graying now and you take the elevator for anything over a couple of flights when, with disconcerting suddenness, the forgotten master arrives—as Koechlin seems to have done. But such arrivals are more likely deceptive than decisive and, in the press of business (e.g., those "nonexistent" stock numbers), the collapse of empires, ozone depletion, oil crises, and the simultaneous crowding in of an incredible and bewildering number of other forgotten masters—to say nothing of the quick and neglected—the newly revealed master may suffer eclipse, occultation even, and depart as suddenly as he came. Which is to say that, if Kocchlin's varieties of luminosity have settled on your ear, you are best advised to grab these fast.

It is, perhaps, because Koechlin is so much the musician's musician that he attracts first-rate, adventurous, virtuosic musicians and draws from them such exquisite care. The song and flute albums, for instance, are as composed as the music, offering works representative of the vastness and extremities of his oeuvre, of its charms and challenges, its miniatures and monstrosities, that is—within the compass of single programs—its staggering variety, through which one is led with rare and radiant assurance. A not intentionally invidious comparison—in his generous offering of horn pieces, Barry Tuckwell Plays Koechlin (ASV CD DCA 716), Tuckwell is no less accomplished than the artists cited above, and no one who cares for Koechlin will willingly be without it, but the inevitable monotony of seventy-eight minutes of music for one instrument, a good bit of it unaccompanied (though, by overdubbing, we have pieces for two, three, and four horns), makes it an album to be sampled piecemeal, where the fantastically shifting soundscapes of the song program, and the deft alternation of brightly brief and pithily extended flute works with pieces offering the relief of vocal obbligato, carry one deliciously and irresistibly to the end. On a smaller scale, the same is true of Lajos Lencsés's collection—though the works are fewer, and cover less ground chronologically and stylistically, their timbrai variety is greater. Finally, Herbert Henck's masterly reading of the suite Les Heures persanes follows the subtly shifting refractions of Koechlin's light-obsessed imagination through one of his most ambitious works.

Sound for these albums is generally optimum, and the accompanying materials range from well done (from Audite) to superb. The song album and sung portions of the flute program are matched with texts and translations. Nor should one underestimate the virtue of informed, lucid annotation in prompting the ear to assimilate novelty to pleasure, in point of which these albums excel.

The liner notes for the song album, by the way, are by none other than Dr. Robert Orledge, author of Charles Koechlin (1867-1950): His Life and Works. Following its subject, this is a large and labyrinthine book. As his dates remind us, Koechlin enjoyed a long and amazingly productive life, his works running to 226 opus numbers, many of which (as in Reger's catalog) cover a surprising number of independent works. Self-borrowing, the assembly of multi-movement works from older pieces, several scorings of individual works (e.g., the Symphony No. 1 and the String Quartet No. 2 are the "same" works, Les Heures persanes was orchestrated, while the orchestral tone poem Au loin exists in an arrangement for harp and English horn), and the like, afford rich complications which the body of the book is occupied in tracing.

Along the way, Orledge describes Koechlin's working methods, and renders a painstaking account of his technical resourcefulness through all its unfoldings, pointed by over a hundred music quotations (many quite extensive), and laced with revealing references to the aesthetic crosscurrents—literary, pictorial, cinematic, and, of course, musical—in the heady swirl of which his own oeuvre rose imperturbably and majestically. This awareness of complex interrelationships is evident on every page—Inseparable from their poly tonal support are Koechlin's long sinuous melodic lines, which at times recall art nouveau arabesques and at others suggest the suppleness of plainsong, especially when they are accompanied by parallel chords in organum. In Le Chant du chevrier [from the piano suite Paysages et marines] Koechlin deliberately keeps the line of the French goatherd's pipe separate from the glowing, wide-spaced chords which support but never overbalance it, creating a perspective of distance and open spaces. . . . The free, fluid melody of the final Poème virgilien again makes little use of exact repetition, and in the suite as as a whole diverse elements combine to create an overall equilibrium—just like that of Nature herself.

Suggestive as this may be—and valuable in its fluent demonstration that Koechlin's language assumes the entire musical past to be contemporary and expressive—it stops short of genuine helpfulness before the sensuously appealing yet bewildering strangeness of hearing Koechlin's longer works. One wants to know how the music works—or is intended to work—since this is not always evident even to close, repeated attention. Certainly, as Koechlin tells us, his music "demands a certain degree of concentration," but the balance from effort to pleasure—and this music affords pleasures like no other—might be achieved more readily through a detailed examination of the ways by which "diverse elements combine to create an overall equilibrium." Indeed, the more ambitious the work, the more necessary this becomes. In this instance, as throughout the book, Paysages et marines and Les Heures persanes are dispatched in passing with tidy generalizations establishing some "truth" about Koechlin sub specie aetemitatis. The listener ungifted with an eternity for this sort of contemplation and who wishes to make aural sense, say, of the seemingly chaotic events of La Course de printemps, which, as the title suggests, sweeps and twists like a force of nature for over half an hour, and who turns to Dr. Orledge for help, will not find it. Some of Koechlin's works, in fact—e.g., the Sept Chansons pour Gladys and parts, at least, of Les Heures persanes—seem to demand new modes of auditory relation touching the penumbra of consciousness, and of this there is no word.

The reader will, however, find here a concise biography; an account of the vicissitudes of Koechlin's reputation; a close and admiring look at his theoretical works and compendious Traité de l'orchestration; teasing descriptions of and quotations from unpublished and unrecorded works in the course of a remarkably wide-ranging survey; a fascinating narrative of Koechlin's infatuation with Lillian Harvey and other stars of the silent screen—and of the music they inspired; a translation of Koechlin's own self-aware—if occasionally also self-justifying—self-assessment; a number of revealing side-glances at composers as diverse as Franck and Chabrier (who were still at work while Koechlin was a young man), his master, Faúré, Debussy (whose Khamma he orchestrated), friends such as Ravel, Sauguet, and Milhaud, and reactions to Schoenberg, Berg, and Cole Porter—for starters; a complete catalog of the works running to some ninety pages; an extensive bibliography; a thorough, useful—indeed necessary—index to discussions of the works; and thirty-seven photographs. No doubt, this volume will prompt specialized studies bringing greater scrutiny to bear upon smaller segments of Koechlin's oeuvre, and from these, eventually, an informed literature for the non-specialist, non-academic listener will develop. Meanwhile, it is unlikely that such largesse—so comprehensive yet keenly detailed an account—will appear again in the forseeable future.

Here, then, is a richly colored topographical map to the dark continent of Koechlin's music, lighted by four exemplary collections of representative works. Taken with recent issues of the great orchestral poems, The Jungle Book (Cybelia CY 679/680, two black discs—long overdue for CD issue—Fanfare 10:1) and Le Buisson ardent (Cybelia CY 812, Fanfare 11:3) it is possible now to get to the radiant heart of "le cas Koechlin." Seldom has a forgotten master arrived so splendidly— though, as noted, the station is crowded and there are frequent departures.

By chance, one hears something haunting. The composer may have been encountered in footnotes but had remained innocent of auditory associations. Small and not very representative pieces may be available as filler and one collects them, becoming more intrigued—as shelf space disappears beneath umpteen mediocre performances of the basic repertoire items one endures for the privilege. Reference books serve mainly to tantalize, the best of them with complete catalogs and tidings of large, rarely performed works marking grand syntheses. Descended from these, album copy tends to be a circus of undigested (mis-)information, dutifully parroted by reviewers to create an odd consensus about a body of music which only a very few people could know at first hand; though, occasionally (notably, on early LP jackets), gracefully revealing notes by uncelebrated, even anonymous, writers will prompt the ear and prime the spirit with a loving erudition surpassing anything in scholarly sources. Slowly, the picture fills in as stalking the elusive forgotten master becomes a passion. One searches old and foreign catalogs, canvasses out-of-print dealers, turns up antique vinyl and ancient monographs in languages in which one is not fluent, and scarce, expensive sheet music which remains impervious to the assaults of one's musicianship. The large, epochal works receive once-in-a-decade (or two, or three) performances and circulate on tape, pirate recordings, or short-lived commercial issues. Reputations shift a bit as dissertation topics thin, and the picture takes on overwhelming, highly specific detail. One is graying now and you take the elevator for anything over a couple of flights when, with disconcerting suddenness, the forgotten master arrives—as Koechlin seems to have done. But such arrivals are more likely deceptive than decisive and, in the press of business (e.g., those "nonexistent" stock numbers), the collapse of empires, ozone depletion, oil crises, and the simultaneous crowding in of an incredible and bewildering number of other forgotten masters—to say nothing of the quick and neglected—the newly revealed master may suffer eclipse, occultation even, and depart as suddenly as he came. Which is to say that, if Kocchlin's varieties of luminosity have settled on your ear, you are best advised to grab these fast.

It is, perhaps, because Koechlin is so much the musician's musician that he attracts first-rate, adventurous, virtuosic musicians and draws from them such exquisite care. The song and flute albums, for instance, are as composed as the music, offering works representative of the vastness and extremities of his oeuvre, of its charms and challenges, its miniatures and monstrosities, that is—within the compass of single programs—its staggering variety, through which one is led with rare and radiant assurance. A not intentionally invidious comparison—in his generous offering of horn pieces, Barry Tuckwell Plays Koechlin (ASV CD DCA 716), Tuckwell is no less accomplished than the artists cited above, and no one who cares for Koechlin will willingly be without it, but the inevitable monotony of seventy-eight minutes of music for one instrument, a good bit of it unaccompanied (though, by overdubbing, we have pieces for two, three, and four horns), makes it an album to be sampled piecemeal, where the fantastically shifting soundscapes of the song program, and the deft alternation of brightly brief and pithily extended flute works with pieces offering the relief of vocal obbligato, carry one deliciously and irresistibly to the end. On a smaller scale, the same is true of Lajos Lencsés's collection—though the works are fewer, and cover less ground chronologically and stylistically, their timbrai variety is greater. Finally, Herbert Henck's masterly reading of the suite Les Heures persanes follows the subtly shifting refractions of Koechlin's light-obsessed imagination through one of his most ambitious works.

Sound for these albums is generally optimum, and the accompanying materials range from well done (from Audite) to superb. The song album and sung portions of the flute program are matched with texts and translations. Nor should one underestimate the virtue of informed, lucid annotation in prompting the ear to assimilate novelty to pleasure, in point of which these albums excel.

The liner notes for the song album, by the way, are by none other than Dr. Robert Orledge, author of Charles Koechlin (1867-1950): His Life and Works. Following its subject, this is a large and labyrinthine book. As his dates remind us, Koechlin enjoyed a long and amazingly productive life, his works running to 226 opus numbers, many of which (as in Reger's catalog) cover a surprising number of independent works. Self-borrowing, the assembly of multi-movement works from older pieces, several scorings of individual works (e.g., the Symphony No. 1 and the String Quartet No. 2 are the "same" works, Les Heures persanes was orchestrated, while the orchestral tone poem Au loin exists in an arrangement for harp and English horn), and the like, afford rich complications which the body of the book is occupied in tracing.

Along the way, Orledge describes Koechlin's working methods, and renders a painstaking account of his technical resourcefulness through all its unfoldings, pointed by over a hundred music quotations (many quite extensive), and laced with revealing references to the aesthetic crosscurrents—literary, pictorial, cinematic, and, of course, musical—in the heady swirl of which his own oeuvre rose imperturbably and majestically. This awareness of complex interrelationships is evident on every page—Inseparable from their poly tonal support are Koechlin's long sinuous melodic lines, which at times recall art nouveau arabesques and at others suggest the suppleness of plainsong, especially when they are accompanied by parallel chords in organum. In Le Chant du chevrier [from the piano suite Paysages et marines] Koechlin deliberately keeps the line of the French goatherd's pipe separate from the glowing, wide-spaced chords which support but never overbalance it, creating a perspective of distance and open spaces. . . . The free, fluid melody of the final Poème virgilien again makes little use of exact repetition, and in the suite as as a whole diverse elements combine to create an overall equilibrium—just like that of Nature herself.

Suggestive as this may be—and valuable in its fluent demonstration that Koechlin's language assumes the entire musical past to be contemporary and expressive—it stops short of genuine helpfulness before the sensuously appealing yet bewildering strangeness of hearing Koechlin's longer works. One wants to know how the music works—or is intended to work—since this is not always evident even to close, repeated attention. Certainly, as Koechlin tells us, his music "demands a certain degree of concentration," but the balance from effort to pleasure—and this music affords pleasures like no other—might be achieved more readily through a detailed examination of the ways by which "diverse elements combine to create an overall equilibrium." Indeed, the more ambitious the work, the more necessary this becomes. In this instance, as throughout the book, Paysages et marines and Les Heures persanes are dispatched in passing with tidy generalizations establishing some "truth" about Koechlin sub specie aetemitatis. The listener ungifted with an eternity for this sort of contemplation and who wishes to make aural sense, say, of the seemingly chaotic events of La Course de printemps, which, as the title suggests, sweeps and twists like a force of nature for over half an hour, and who turns to Dr. Orledge for help, will not find it. Some of Koechlin's works, in fact—e.g., the Sept Chansons pour Gladys and parts, at least, of Les Heures persanes—seem to demand new modes of auditory relation touching the penumbra of consciousness, and of this there is no word.

The reader will, however, find here a concise biography; an account of the vicissitudes of Koechlin's reputation; a close and admiring look at his theoretical works and compendious Traité de l'orchestration; teasing descriptions of and quotations from unpublished and unrecorded works in the course of a remarkably wide-ranging survey; a fascinating narrative of Koechlin's infatuation with Lillian Harvey and other stars of the silent screen—and of the music they inspired; a translation of Koechlin's own self-aware—if occasionally also self-justifying—self-assessment; a number of revealing side-glances at composers as diverse as Franck and Chabrier (who were still at work while Koechlin was a young man), his master, Faúré, Debussy (whose Khamma he orchestrated), friends such as Ravel, Sauguet, and Milhaud, and reactions to Schoenberg, Berg, and Cole Porter—for starters; a complete catalog of the works running to some ninety pages; an extensive bibliography; a thorough, useful—indeed necessary—index to discussions of the works; and thirty-seven photographs. No doubt, this volume will prompt specialized studies bringing greater scrutiny to bear upon smaller segments of Koechlin's oeuvre, and from these, eventually, an informed literature for the non-specialist, non-academic listener will develop. Meanwhile, it is unlikely that such largesse—so comprehensive yet keenly detailed an account—will appear again in the forseeable future.

Here, then, is a richly colored topographical map to the dark continent of Koechlin's music, lighted by four exemplary collections of representative works. Taken with recent issues of the great orchestral poems, The Jungle Book (Cybelia CY 679/680, two black discs—long overdue for CD issue—Fanfare 10:1) and Le Buisson ardent (Cybelia CY 812, Fanfare 11:3) it is possible now to get to the radiant heart of "le cas Koechlin." Seldom has a forgotten master arrived so splendidly— though, as noted, the station is crowded and there are frequent departures.

Soon after the review of the above cited Audite disc appeared, a reader wrote privately to ask if the album number were correct—the distributor