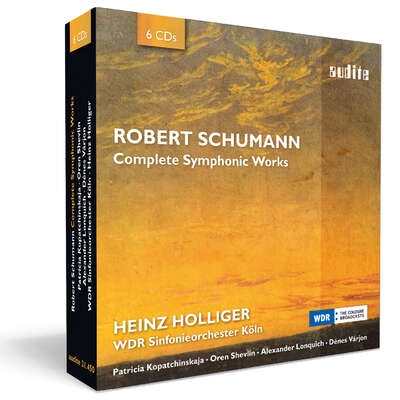

Für die zweite Folge der Gesamteinspielung von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken haben Heinz Holliger und das WDR Sinfonieorchester Schumanns Sinfonien in der Orchesterstärke eingespielt, die dem Komponisten selbst bei Aufführungen in Leipzig und Düsseldorf zur Verfügung stand. Die Streicher waren dabei schwächer besetzt als heute üblich. Dadurch gewinnt der Klang an Plastizität und an Differenziertheit in den instrumentalen Farben. So wird unmittelbar verständlich, weshalb Zeitgenossen an den beiden großen zyklischen Werken (der Entstehung nach die beiden letzten Symphonien Schumanns) neben ihrer Charakteristik vor allem die kunstvolle und überzeugende Orchestrierung hervorhoben. Holligers Interpretationen beruhen auf seiner fast lebenslangen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk, dem Denken, der Persönlichkeit und dem Schicksal Robert Schumanns. Holligers Ansatz verleiht den opulenten Partituren durch hierarchische Stimmenbalance, fein abgestufte Dynamik und frische Tempi Transparenz und Leichtigkeit. Das verbreitete Bild dieses Romantikers als schwacher Orchestrator erfährt dadurch eine erfrischende und fundierte Korrektur. mehr

Für die zweite Folge der Gesamteinspielung von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken haben Heinz Holliger und das WDR Sinfonieorchester Schumanns Sinfonien in der Orchesterstärke eingespielt, die dem Komponisten selbst bei Aufführungen in Leipzig und Düsseldorf zur Verfügung stand. Die Streicher waren dabei schwächer besetzt als heute üblich. Dadurch gewinnt der Klang an Plastizität und an Differenziertheit in den instrumentalen Farben. So wird unmittelbar verständlich, weshalb Zeitgenossen an den beiden großen zyklischen Werken (der Entstehung nach die beiden letzten Symphonien Schumanns) neben ihrer Charakteristik vor allem die kunstvolle und überzeugende Orchestrierung hervorhoben. Holligers Interpretationen beruhen auf seiner fast lebenslangen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk, dem Denken, der Persönlichkeit und dem Schicksal Robert Schumanns. Holligers Ansatz verleiht den opulenten Partituren durch hierarchische Stimmenbalance, fein abgestufte Dynamik und frische Tempi Transparenz und Leichtigkeit. Das verbreitete Bild dieses Romantikers als schwacher Orchestrator erfährt dadurch eine erfrischende und fundierte Korrektur.

Details

| Robert Schumann: Complete Symphonic Works, Vol. II | |

| Artikelnummer: | 97.678 |

|---|---|

| EAN-Code: | 4022143976789 |

| Preisgruppe: | BCA |

| Veröffentlichungsdatum: | 18. Juli 2014 |

| Spielzeit: | 66 min. |

Zusatzmaterial

Informationen

Mit dieser CD legt audite die zweite Folge der Gesamteinspielung von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken vor. Die Serie umfasst sämtliche Sinfonien (inkl. beider Fassungen der Vierten) sowie alle Ouvertüren und Konzerte. Die nach üblicher Zählung Zweite und Dritte Sinfonie durchliefen eine gegensätzliche Rezeptionsgeschichte. Während die 'Rheinische' relativ populär blieb, wurde die C-Dur-Sinfonie von den Zeitgenossen zwar als richtungsweisend aufgenommen, geriet aber ab Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts in den Hintergrund. Kritisiert wurde zu diesem Zeitpunkt die Instrumentation, die nach der Uraufführung noch gelobt worden war. Heinz Holliger und das WDR-Sinfonieorchester haben die Werke in der Orchesterbesetzungsgröße eingespielt, die Schumann zur Verfügung stand. Sie legen dadurch nicht nur das Klangideal des Komponisten frei, sondern auch dessen stimmige und überzeugende Verwirklichung. Holligers Interpretationen beruhen auf seiner fast lebenslangen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk, dem Denken, der Persönlichkeit und dem Schicksal Robert Schumanns. Holligers Ansatz verleiht den opulenten Partituren durch hierarchische Stimmenbalance, fein abgestufte Dynamik und frische Tempi Transparenz und Leichtigkeit. Das verbreitete Bild dieses Romantikers als schwacher Orchestrator erfährt dadurch eine erfrischende und fundierte Korrektur.

Besprechungen

Gramophone | August 2019 | Richard Whitehouse | 1. August 2019

THE ULTIMATE CHOICE

Nine decades of recordings reflect changing attitudes to Schumann’s Second

This leaves Heinz Holliger with the WDR Symphony of Cologne as prime recommendation. Long crucial to his work as composer and conductor, Holliger’sMehr lesen

Almost 175 years since its completion, Schumann’s Second Symphony can, more than ever, be heard as the true embodiment of musical mid-Romanticism, as well as being the salient symphonic achievement from that interregnum stretching between Schubert and Bruckner.

Schumann has long been central to Heinz Holliger’s creative thinking. His Cologne account – part of the most inclusive overview of Schumann’s orchestral works to date – fuses chamberlike clarity, authenticstyle astringency and full-orchestral immediacy for astounding results.

Thüringen Kulturspiegel | Mai 2016 | Dr. Eberhard Kneipel | 1. Mai 2016

AIte Schönheit - neuer Glanz

Die Gesamtaufnahme von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken beim Edel-Label audite

Erster Anlauf, erstaunliche Experimente, imponierende Meisterwerke: Ein außergewöhnliches und an Entdeckungen reiches Hör-Erlebnis ist zu haben – auch dank audite!Mehr lesen

Stuttgarter Zeitung | 22.03.2016 | Dr. Uwe Schweikert | 22. März 2016

Eine Großtat für Robert Schumann

Heinz Holliger und das WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln nehmen das gesamte sinfonische Werk auf

Man sagt wohl nicht zu viel, wenn man diese CDs als die wichtigste Schumann-Einspielung seit langem rühmt. Sie beweist, dass es keines historischen Instrumentariums und auch keines Spezialistenensembles bedarf, um die Werke aus dem Geist der Zeit für heute aufs Neue zu verlebendigen.Mehr lesen

NDR Kultur | 21. Januar 2016

BROADCAST

"Matinee"

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

classical ear | Friday August 15 | Colin Anderson | 15. August 2015 | Quelle: http://classical...

Dedicated playing and excellent sound complete this notable release; believe me, five stars are not enough.Mehr lesen

www.opusklassiek.nl | mei 2015 | Siebe Riedstra | 1. Mai 2015

De Zwitserse hoboïst, componist en dirigent Heinz Holliger heeft zich in al zijn disciplines intensief met het werk van Schumann beziggehouden. Als componist leidde dat tot verassende resultaten, getuige zijn Romancendres (hier besproken door Aart van der Wal). Als dirigent munt Holliger in de eerste plaats uit door een buitengewoon scherp en precies gehoor, tot op de Herz nauwkeurig. Zijn slagtechniek sluit niet naadloos aan op die precisie, en dat hoor je bijvoorbeeld in de wat rommelige start van de Eerste symfonie. Mehr lesen

Schumann-Journal | Nr. 4 / Frühjahr 2015 | Jan Ritterstaedt | 1. April 2015

Die Folgen 2 und 3 der neuen Gesamteinspielung sämtlicher sinfonischer Werke Robert Schumanns setzt die mit der ersten CD begonnene Interpretationslinie konsequent fort. Hier entsteht eine Reihe von Aufnahmen, die einen sicherlich sehr individuellen, in gewisser Weise auch modernen, vor allem aber künstlerisch sehr wertvollen Beitrag zur Schumann- Diskografie leistet. Man darf jetzt schon auf das nächste Produkt dieser Serie gespannt sein!Mehr lesen

Gramophone | 17.03.2015 | Philip Clark | 17. März 2015

Music that grapples with demons and is never wholly at ease, even when wings bless the darkness with glimpses of light—when you’re RobertMehr lesen

The symphonic models are clear and we hear the ghostly spectre of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn—but no one has told Schumann’s material that it needs to conform, and the music cannot help but spill over any frame its composer attempts to place around it. The first movement of his Symphony No 1 reaches an apparent cathartic end-point as a solo flute line marked dolce reconciles grinding harmonic and structural inner tensions. Time to stop this madness. But then brass, percussion and trilling woodwinds unleash a stampeding burlesque march. Baleful chromatic inclines smudge the harmony, like Offenbach or Sousa turned on their dark side, and such instability derives from the restlessness of Schumann’s mind, you think, rather than being an overtly conceptual compositional strategy. The free jazz of the Second Symphony’s sostenuto assai prologue, C major credentials asserted by having the strings play anything but, as the brass sustain pure C major triads; in the Third Symphony, that extra movement that sneaks in before the finale, a cobwebby and gothic reimagining of the grounding contrapuntal principles of Renaissance music and Bach; and the audacious cyclic structure of the Fourth Symphony, each movement played attacca and dovetailing into the next. This music of demons and angels grapples also with angles—to take on structure, awkward punctuation, Schumann pushing form, his personal mission being to remould the symphony. And when the realisation dawns that Schumann composed the first version of what would become his Fourth Symphony in the same year as his First Symphony, eyes blink in astonishment. The natural order of things would be to presume that Schumann’s streamlined Fourth Symphony is a perfect distillation of the first three symphonies—but the pathway through Schumann’s symphonic journey is filled with unexpected and improbable twists and turns.

Deciding to record a cycle of the Schumann symphonies begs the question: what exactly should be recorded? And complementary but divergent ideas about the Schumann symphonies have been paraded as rarely before, with four major conductors during the past 18 months releasing four major cycles on disc. Sir Simon Rattle, with the Berlin Philharmonic, gives us four symphonies with the early 1841 version of the Fourth, while Yannick Nézet-Séguin (and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe) and Robin Ticciati (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra) opt for Schumann’s 1851 revised version. But Heinz Holliger and the WDR Symphony Orchestra of Cologne—like Sir John Eliot Gardiner and his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, whose trailblazing 1997 Schumann cycle was given the boxed-up DG reissue treatment last year—perceive Schumann’s symphonic evolution in seven stages. When Holliger completes his cycle during the next year and a half, Schumann’s early Symphony in G minor (the Zwickau Symphony) will take its place alongside the first three canonic symphonies, both versions of the Fourth, and the oftenoverlooked mini-me symphony Overture, Scherzo and Finale—Schumann’s compositional twists of fate put into historical context by a composer/conductor/oboist who has been obsessed with the composer’s enigma for more than 40 years.

I made Rattle’s cycle my Critics’ Choice album of the year in the December 2014 issue; I’ve also elevated Nézet-Séguin’s to an equivalent position in the past. Ticciati’s set has given me much pleasure too, and even more to think about. Nézet-Séguin and Ticciati deploy chamber-orchestra string sections, with Ticciati most explicitly evoking period-instrument practice. Rattle’s Berlin set carries its weightier orchestral ballast very elegantly, and his set became my portal back to Schumann after a longer period than I care to admit when my listening had been dominated by Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Rattle’s opulent, rapacious approach—the climax of the First Symphony’s opening movement and the Trio in the Second Symphony’s Scherzo seemingly moving faster than time itself, while the Berlin strings float the slow movement towards heaven—represented the warmest welcome back possible to Schumann’s dream-built chimeric fantasy world, the heartfelt directness of his melodic fancy played out over structural chess moves. Ticciati’s sometimes manically driven, flintier orchestral sound can be unexpectedly austere; Nézet-Séguin’s cycle is the most unashamedly Romantic of the four, fevered-brow gesturing, rubato with attitude.

Despite their differences, though, the sets are unified by one underlying common denominator—none of them could have been recorded 30, or even 20, years ago. Over the phone from his home in Zurich, Heinz Holliger suppresses a laugh when I ask: why now? Why, suddenly, have maestros gone all Schumann crazy? ‘Well, I started conducting him 30 years ago, when too many conductors had problems with Schumann,’ he reflects. ‘He was never a problem for pianists or composers—Debussy and Berg held him in great esteem—but conductors realised that you cannot try to sight-read Schumann; if you do, the music is completely grey.’ And even 50 shades of grey would not be enough to express Schumann’s multiverse of colour? ‘He does not write out everything; he doesn’t tell you which voice is the principal and which accompanies; nor whether one instrument should have a diminuendo while the others crescendo. To make a Schumann symphony sound light and transparent, as he intended, takes a lot of rehearsal. Each player needs to know whether they’re playing part of only the harmony, or whether they are involved in the counterpoint. Schumann was a great writer of words too, and you need to understand how close the phrasing is to speech. But many conductors are not so interested in this background; they just play what they read.’

Holliger reminds me that Schumann never heard more than 12 first violins during his whole life and, in his view, the period-instrument movement has had a very positive effect on how conductors perceive appropriate orchestral weighting and internal balance. And when I talk to Sir Simon Rattle a few weeks earlier, he makes a characteristically smart analogy: ‘We think of Beethoven and Brahms as being the grizzled old lions of Austro-German symphonic tradition,’ he tells me, ‘but Schumann’s symphonies move like a panther. Beethoven plunges his feet forcefully through the ground; but Schumann’s feet sprint and never fully touch the floor.’

Rattle can’t quite explain why Schumann is suddenly so de rigueur, although sometimes, he says, mysterious forces collude to raise the collective consciousness around a particular composer. But the important thing for Rattle is that distinct and informed conductorly perspectives must all be celebrated. Ticciati’s way is not his way, but Rattle admires enormously how he tackles the 1851 revision of the Fourth Symphony: ‘Robin makes a clear case for how the revised version can retain the radical edge of the 1841 version. Still it sounds like a fireball and I take my hat off to him.’

Which Fourth Symphony? That’s the most fundamental decision any wannabe Schumann conductor must make. To programme the 1841 version is to agree with Brahms, who owned the autograph score and wrote: ‘It is a real pleasure to see anything so bright and spontaneous expressed with corresponding ease and grace.’ He found the revised version charmless and stodgy, and Rattle and Holliger concur with Brahms, and each other, that the first version is much preferable—although they choose to do notably different things with that information. ‘Schumann made the revised piece in a depressive state,’ Rattle says, ‘and Brahms was completely right about the relative merits of the two versions.’ Holliger adds that Schumann’s orchestra in Düsseldorf, which premiered the new version, was nowhere near as honed as the standard of playing he had become accustomed to in Leipzig, while Schumann himself ‘was heavier, and moved and spoke more slowly’. But the pertinent point for Holliger is that Schumann retained his high-velocity metronome marks. Rattle chooses to ignore the later rewrite—Holliger gives us both but attempts to play the 1851 version, as he says, ‘retaining the true spirit of the earlier version’.

Holliger reminds me that he met Rattle 40 years ago when the young conductor invited him to perform Richard Strauss’s Oboe Concerto with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. And Rattle clearly remains in awe of Holliger’s status as a Schumann guru—‘Ask Heinz, when you speak to him, to tell you about the tempo relationships in the symphonies and about his extraordinary discovery in the fourth movement of the Rhenish Symphony.’ And I’m happy to take my cue from the Music Director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

On paper, and in the mind, Schumann’s Second Symphony registers as the most conventionally ‘symphonic’, its four movement groundplan—with a slow introduction breaking into an Allegro trot—putting you in mind of the first two Beethoven symphonies or of Haydn. And as I began to reacquaint myself with Schumann’s symphonic world, I pondered how a composition that felt instinctively unified melodically and motivically could also sound so disparate and varied, like each movement acting as a standalone character piece (not that you would necessarily want that). Holliger provides an answer.

‘The first and second movements,’ he tells me, ‘have the same metronome mark of crotchet=144, and the slow movement is nearly half; then the finale is in a very fast one-beat-per-bar, but still you feel like each bar matches the beat of the slow movement. The whole symphony is in one, like the conception of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony.’ Holliger explains how the music is glued together throughout by a four-note cell, but I ask him to tell me about the music’s disunity. Am I right to hear each movement orbiting independently too, in a way that is uniquely Schumann? Holliger alludes to Bernd Alois Zimmermann, the composer of Die Soldaten, Photoptosis and Requiem für einen jungen Dichter, who died in 1970, and who was famous for pieces that made liberal use of collage and knitted together layers of borrowed material. ‘He was fascinated by the idea of Kugelgestalt—that time is like a ball, and all times of all centuries are focused in one single point. I think Schumann understood this too. You ask about the Second Symphony—well, the beginning could be like 17thcentury polyphony and then, suddenly, it looks 120 years or more into the future. You feel this composer knows the whole history of music.’

The Second Symphony’s Scherzo has something of the lightness of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Holliger explains as he tells me about those angels and demons, ‘but is relentless, a diabolic dance, in the mood of ETA Hoffmann’. And that shockingly abrupt change of mood, the solo flute overtaken by a brutal march as the first movement of the First Symphony reaches its climax, is another characteristic Schumann moment. ‘In the First Symphony the flute symbolises a butterfly which here is overwhelmed by very tragic music. Marches are a frightening thing. Send soldiers to kill, and you’re asking them to stop thinking about what they are doing. Trills in Schumann, like the woodwind trills you mention, often tremor and shiver like music with a high fever—this is not the Baroque idea of a trill as ornamentation.’

Holliger talks about the symbolism of instrumental identity in Schumann’s music. In Overture, Scherzo and Finale a choir of three trombones appear suddenly like a premonition of the role they will take in the fourth movement of the Rhenish. ‘When his brother Eduard was dying, Schumann woke up at three in the morning. He had been dreaming about three trombones, and later he learnt that his brother had died at 3am. Always in Schumann, three trombones is a message about death.’ I mention that Rattle urged me to ask him about this same movement. ‘Well, when I looked at the sketches, I realised that the tempo changes to double the speed two beats later than in the printed score—nobody ever does this, but the difference is essential.’

That Schumann had such specific ideas about orchestral colour and instrumental identity runs triumphantly contrary to that tired cliché about his orchestration being somehow inept and clumsy. In the September 2014 issue of Gramophone, Robin Ticciati revealed that, for him, the attraction of Schumann is precisely because the orchestration is so, as he put it, ‘crazy’. ‘It’s also so controlled, and the palette is extraordinary. And I think when you get to a Schumann score, the first reaction is not to go, “What is all that?” but “What does he want?” and “What’s important here?”’ Ticciati hears clues about how Schumann ought to sound orchestrally in how he ‘orchestrates’ his piano music; and in the booklet-notes accompanying his cycle, Yannick NézetSéguin discusses how the defined attack and decay of modern trumpets help balance the orchestration.

And so Schumann wins. The consensus, circa 2014/15, is leave well alone. ‘Schumann learnt lots about orchestration from Mendelssohn, the greatest orchestrator of his time,’ Holliger explains, ‘and he tried to have a very transparent sound in the orchestra. It’s not that very heavy “German potato soup” sound. I never change a single note in any of the symphonies.’ Rattle confirms that Schumann must be ‘light and singing, or the sound can be too brittle—the key word is sostenuto.’ The impulsive and spontaneous side of Schumann is also important to Rattle. ‘The last symphonic music Schumann wrote was the Rhenish,’ he says, ‘and the fourth movement feels like Schumann falling apart, then the finale is an attempt to cradle him in a warm embrace. And for that to work, you can’t micromanage too heavily.’ Music to Schumann’s ears, I suspect—a composer who clearly knew the value of spontaneity: ‘My symphonies would have reached Opus 100 if I had but written them down,’ he said. ‘Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible to write anything.’

Diapason | N° 630 Decembre 2014 | Rémy Louis | 1. Dezember 2014

Deuxième étape (cf n° 622 pour le Volume 1) de ce qui s'impose comme un des cycles Schumann majeurs des années récentes. Il n'en a pourtant pasMehr lesen

Ruptures, surprises, exaltations, ivresse: il y a tout cela dans l'Allegro ma non troppo qui s'y enchaîne (on les retrouvera dans l'Allegro molto vivace final). Reposant sur un art des contrastes et une recherche d'équilibre très élaborés, il dégage un paysage sonore plus précis et varié à la fois, plus aéré que dans les gravures « romantiques » usuelles (brahmsiennes, en vérité: la contagion s'est opérée à rebours), créant ainsi une autre poétique. Le Scherzo revient à des origines classiques, allègres, dansantes, l'Adagio espressivo est étranger à tout pathos. On aime le grand geste processionnel auquel certains s'abandonnent ici – Leopold Stokowski, par exemple. Mais on admire tout autant, dans une esthétique et des moyens ô combien éloignés, le dialogue différencié, la légèreté et la fraîcheur que Holliger obtient d'un orchestre très réactif... sans d'ailleurs renoncer à une certaine élégance (la noblesse vraie de la fin du dernier mouvement).

La « Rhénane » confirme ce rééquilibrage au profit des bois, cordes agiles et dégraissées, effectif resserré. Ce n'est plus le Rhin à son plus large et majestueux, mais à sa source, jaillissant, changeant. Les Lebhaft remontent ainsi aux sources du romantisme. Un sourire imprègne le Scherzo (écoutez bien les bois, et l'évidence des équilibres), le Nicht Schnell devient une rêverie intime mais toujours allante. Et la proximité d'approche du Feierlich avec l'Adagio de la Symphonie n° 2 est frappante. Une magnifique réussite.

Fono Forum | Dezember 2014 | Stephan Schwarz | 1. Dezember 2014

Kritiker-Umfrage 2014

Die 10 besten Aufnahmen des Jahres 2014

Selten hatte man das Gefühl, ein Dirigent könnte einem Komponisten so in den Kopf schauen wie Heinz Holliger Robert Schumann.<br /> Mehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | November 2014 | EL | 1. November 2014

Holliger brings amazing textural clarity to the composer's orchestration without ever sacrificing the expressive Intensity of the musical argument.Mehr lesen

Hi-Fi News | 01.11.2014 | CB | 1. November 2014

As an instrumentalist (oboe) Holliger’s Schumann discography dates back to 1981. In the role of conductor here, he’s scaled the orchestra back toMehr lesen

www.artalinna.com | 23 octobre 2014 | Jean-Charles Hoffelé | 23. Oktober 2014 L’orchestre réinventé

Soudain l’orchestre se creuse, les accords claquent, le geste devient péremptoire : on le comprend, Schumann symphoniste s’est trouvé. Les pupitres de la WDR peuvent chanter autant qu’ils le veulent, Holliger les accompagne d’un geste enthousiaste, presque avec ivresse.Mehr lesen

International Record Review | October 2014 | John Warrack | 1. Oktober 2014

Heinz Holliger's cycle of Schumann's symphonic works continues in Volume 2 (the first was reviewed in January) with Symphonies Nos. 2 and 3,Mehr lesen

This kind of scrupulousness guides Holliger's performances, together with a naturally light touch in style that suits the works well, and does not treat them as if Brahms had already arrived upon the German scene. He does not take the opening of the Second Symphony too majestically, playing it quite brightly, which suits a movement in which the themes are not developmental but dangerously repetitious. The Scherzo is played swiftly, but with a certain eeriness in the main scherzo, which expresses it well: the swift, apparently dancing theme is actually based on a discord (the ubiquitous Romantic chord of spookiness, the diminished seventh), and the more lyrical elements must lie, as in this performance, with the two Trios which Schumann provides as its counter. The Adagio is marked by length of melodic line in the wind, led by a beautifully played oboe (as no doubt Holliger, one of the great oboists of his time, would have appreciated). Both with this Symphony's finale and that of the other Symphony here, the 'Rhenish', matters are kept bright and quite swift-moving, no attempt being made at a grand climatic summing up.

The Rhine Symphony itself is vividly presented, with the Ländler of the second movement absorbed into the work's Iyrical elements, as is suggested by the movement's intricate treatment of it, rather than played as a splash of local colour; and the movement, really an interlude, is gracefully and elegantly handled. The are problems for the interpreter in the fourth movement, marked feierlich ('solemn' or 'ceremonial'), with its subtle invocations (as Gál again points out) of the length of tradition manifest in the Rhine's great cathedral at Cologne, with motives that have ecclesiastical associations and even of Bach himself, no Rhinelander but a figure in whose shadow so much stood.

These are intelligent interpretations, decently recorded, original but drawing their nature from what lies to be found in the music itself.

Gramophone | October 2014 | David Threasher | 1. Oktober 2014

Rob Cowan reviewed the first volume of Heinz Holliger's Schumann symphony cycle last December and concluded that, as it continued, this 'may well beMehr lesen

In the Second, Holliger demurs from the darkness-to-light trajectory divined by Ticciati and perhaps views the work as primarily derived from a Beethovenian aesthetic rather than a Mendelssohnian one, the notable intensity of the opening movement yielding to a businesslike central pair and a finale that feels more episodic than needs be. It's a similar story in the Rhenish: the 'Cologne Cathedral' movement is amply monumental but short on the mystery distilled by Nezet-Seguin or Ticciati, and again the first movement is the best, if not as ideally detailed as other recent readings.

In its favour, this disc is beautifully recorded, the woodwind favoured just a degree over the strings, allowing their solos to sing out. Brass, too, are given their head, which is especially important in both these works. The WDR SO is a full-size Romantic orchestra with slightly reduced strings for these performances, as opposed to the chamber bands that are increasingly claiming this music as their own; so the direct comparison is to Rattle, sumptuous-sounding if hampered by certain mannerisms, as against Holliger's coolness. You pays your money and you takes your choice: Holliger's cycle will ultimately be on three full-price SACDs, whereas many of the smaller-scale (and commensurately more athletic) performances come in handily priced two-disc slimline packs. Regular readers will already know where my preferences lie.

Record Geijutsu | 10/2014 | 1. Oktober 2014

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Schwäbische Zeitung | Donnerstag, 25. September 2014 | man | 25. September 2014 So klingt „Die Rheinische“ vom Rheinland

Schwung, Rhythmik, Agilität und Leichtigkeit, alles wirkt überzeugend. Und das WDR-Orchester spielt gleichermaßen engagiert wie inspiriert. Der kluge Beitrag im Begleitheft von Habakuk Traber rundet den vorzüglichen Eindruck ab.Mehr lesen

www.concertonet.com | 09/18/2014 | Christie Grimstad | 18. September 2014

This Audite collection is grand and resolute in its interpretation of Schumann’s lively works.<br /> Recommended.Mehr lesen

Recommended.

Süddeutsche Zeitung | Dienstag, 16. September 2014 | Wolfgang Schreiber | 16. September 2014 Klassikkolumne

Da kann Heinz Holliger mit dem Kölner WDR–Sinfonieorchester kräftig punkten.Mehr lesen

www.concertonet.com | 09/15/2014 | Simon Corley | 15. September 2014

Son Schumann se révèle souvent inattendu – pour la Quatrième, il a d’ailleurs préféré la version de 1841, plus abrupte et anguleuse, qu’il est toujours passionnant de confronter à la mouture définitive de 1851: raffiné, aérien, aéré, volontiers chambriste, d’une grande lisibilité, il convainc davantage dans la juvénile Première, dans le triptyque Ouverture, Scherzo et Finale et, peut-être plus encore, dans une puissante et fougueuse Deuxième.Mehr lesen

Infodad.com | September 04, 2014 | Infodad Team | 4. September 2014 Selected Symphonists

These are highly attractive readings in a series that holds considerable promise and is well on the way to fulfilling it.Mehr lesen

Stereoplay | 09/2014 (September 2014) | Michael Stegmann | 1. September 2014 Vier mal vier

Wo Rattle also den Romantiker Schumann betont, Järvi den Klassizisten und Nezet-Seguin den Verrückten, da steht Heinz Holliger mit dem WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln scheinbar zwischen allen Lösungen, was aber nicht unbedingt die schlechteste Wahl ist. [...] Vielleicht hat die Erfahrungs- und Ideenwelt des Komponisten Holliger hier den Taktstock geführt; jedenfalls hat er mich von den vier Aufnahmen am häufigsten überrascht.Mehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | September 2014 | Brian Wilson | 1. September 2014

There’s no special price for the Audite recording but, at $12.02 – just over £7 at current rates – it won’t break the bank and it’s wellMehr lesen

The Audite recording is good throughout, though I miss those powerful drum thwacks, so apparent on the Linn recording. If you bought the first volume (Audite 97.677, Symphony No. 1 and No. 4, original version, and Overture, Scherzo and Finale) I’m sure you’ll want the second. The third volume, containing the Cello Concerto and final version of the Fourth Symphony, is due for release in October 2014.

I should add that I haven’t yet heard the new, highly-regarded BPO/Simon Rattle set – review – except for the 1-minute segments from Qobuz, but I see that he attributes his appreciation of Schumann to a meeting long ago with Heinz Holliger, whom he describes as a Schumann ‘nut’ – endorsement of a kind for his mentor’s new recording.

Audiophile Audition | August 31, 2014 | Gary Lemco | 31. August 2014

Tasteful and enthusiastic, these readings of Schumann by Heinz Holliger capture an esprit entirely appropriate to the occasion.Mehr lesen

http://theclassicalreviewer.blogspot.de | Friday, 15 August 2014 | Bruce Reader | 15. August 2014 Terrific new performances of Schumann’s second and third symphonies from Heinz Holliger and the WDR Sinfonieorchester, Köln on Volume II of Audite’s complete symphonic works series

These terrific new performances are full of so many fine things and should provide an ideal choice of recording for these works. The recordings made in the Philharmonie, Köln are absolutely first class and add so much to the clarity of detail.<br /> <br /> With excellent booklet notes this new release must receive the strongest recommendation.Mehr lesen

With excellent booklet notes this new release must receive the strongest recommendation.

www.pizzicato.lu | 03/08/2014 | Rémy Franck | 3. August 2014 Mehr Schumann mit Holliger

Das WDR Sinfonieorchester und Heinz Holliger setzen ihre Reihe der Einspielungen aller Orchesterwerke von Robert Schumann mit den Symphonien Nr. 2 undMehr lesen

www.classicalsource.com | 01.08.2014 | Antony Hodgson | 1. August 2014 Heinz Holliger conducts Robert Schumann’s Complete Symphonic Works – Volume 2, Second & Rhenish Symphonies

The recorded sound is warm, lucid and realistic. There is more to come in this series and I look forward to it.Mehr lesen

NDR Kultur | 14.07.2014, 15:20 Uhr | Jan Ritterstaedt | 14. Juli 2014

Zusammen mit dem WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln zaubert der Dirigent Heinz Holliger schillernde Farben aus der Partitur von Robert Schumann hervor -Mehr lesen

www.myclassicalnotes.com | Wednesday | 08.06.14 | Hank Zauderer | 8. Juni 2014 Schumann’s Magic

Holliger‘s performances draw on a lifetime study of Schumann‘s music, thought, and personality. His approach imparts lightness and lucidity to these scores through a balance of parts, delicately gradated dynamics and invigorating tempos.Mehr lesen