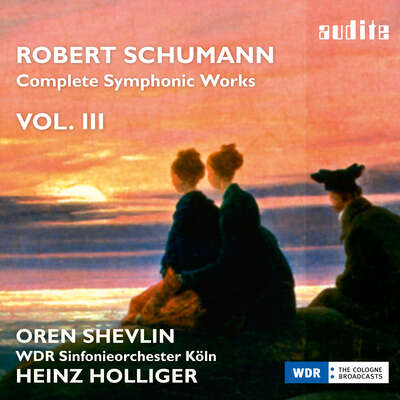

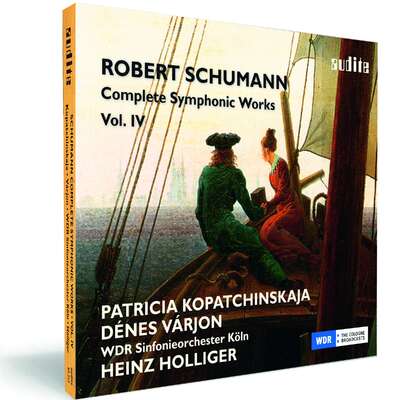

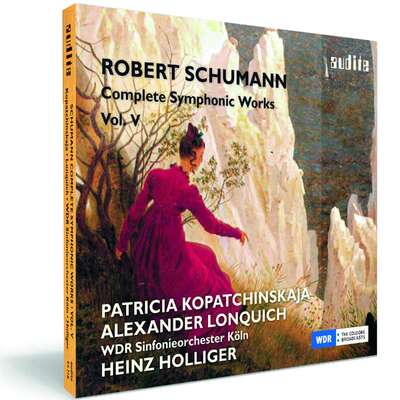

Mit dem Violoncellokonzert und der zweiten Fassung der d-Moll-Symphonie enthält diese CD zwei Hauptwerke aus Schumanns Zeit als Düsseldorfer Musikdirektor. In beiden lässt er die Sätze des klassischen Formmodells ohne Unterbrechung ineinander übergehen. Der Impuls dazu entsprang seinem Wunsch, Gestaltungsformen der Literatur auch für die Musik zu nutzen. Für diese neue Art ihrer Beredtheit brauche die Tonkunst nach seiner Auffassung keine literarischen Programme.mehr

"Schumanns sinfonisches Schaffen hat in letzter Zeit viele Neueinspielungen erlebt, doch der Holliger-Zyklus dürfte, wenn er beendet ist, einen der vorderen Ränge einnehmen." (Stereo)

Details

| Robert Schumann: Complete Symphonic Works, Vol. III | |

| Artikelnummer: | 97.679 |

|---|---|

| EAN-Code: | 4022143976796 |

| Preisgruppe: | BCA |

| Veröffentlichungsdatum: | 10. Oktober 2014 |

| Spielzeit: | 52 min. |

Zusatzmaterial

Informationen

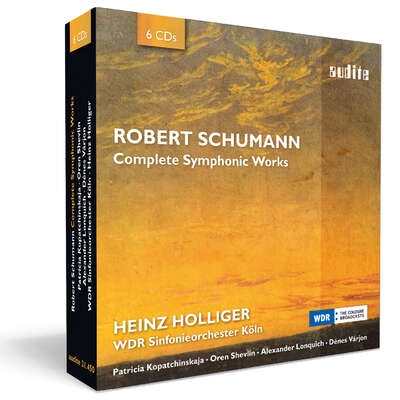

audite legt mit der CD die nunmehr dritte Folge der Gesamteinspielung von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken vor. Die Serie umfasst alle Sinfonien (inkl. beider Fassungen der Vierten in d-Moll) sowie alle Ouvertüren und Konzerte.

Mit dem Violoncellokonzert und der zweiten Fassung der d-Moll-Sinfonie enthält die CD zwei Werke, die Schumann in seiner Zeit als Städtischer Musikdirektor in Düsseldorf komponierte bzw. in revidierter Fassung edierte. In beiden lässt er die verschiedenen Sätze des klassischen Formmodells ohne Unterbrechung ineinander übergehen. Durch Metamorphosen von Themen und musikalischen Chiffren schafft er einen Gedankenfluss und -zusammenhang, der dem Verlauf einer Erzählung oder eines abstrakten Theaters ähnelt. Als er 1841 die Urfassung der d-Moll-Sinfonie schrieb, gelang ihm ein Pionierwerk in der Literarisierung der musikalischen Form. Als er sie 1851 zu überarbeiten begann, waren die ersten Sinfonischen Dichtungen Franz Liszts bereits aufgeführt worden; sie strebten eine engere Fusion von Musik und Literatur an. In seiner Überarbeitung der d-Moll-Sinfonie verstärkte Schumann dezent die traditionell-sinfonischen Momente des Werkes. Die deutlichen Mendelssohn-Bezüge in seinem Cellokonzert verweisen darauf, dass er in mehrteiligen Formen wie in diesen beiden Werken gleichsam »Erzählungen ohne Worte«, also große Geschwister der »Lieder ohne Worte« sah. Beide Genres brauchten, wie er fand, keine Erläuterungen durch ein literarisches Programm.

Die Urfassung der d-Moll-Sinfonie ist auf der ersten CD der Serie enthalten. Beide Versionen, deren Verhältnis zueinander bis heute kontrovers diskutiert wird, können so miteinander verglichen werden.

Holligers Interpretationen beruhen auf seiner fast lebenslangen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk, dem Denken, der Persönlichkeit und dem Schicksal Robert Schumanns. Holligers Ansatz verleiht den opulenten Partituren durch hierarchische Stimmenbalance, fein abgestufte Dynamik und frische Tempi, Transparenz und Leichtigkeit. Das verbreitete Bild dieses Romantikers als schwacher Orchestrator erfährt dadurch eine erfrischende und fundierte Korrektur.

Besprechungen

www.peterhagmann.com

| 13. Juli 2016 | Peter Hagmann | 13. Juli 2016 | Quelle: http://www.peter...

Ein Fall für die ideale Diskothek

Die Orchestermusik Robert Schumanns in Aufnahmen mit dem Dirigenten Heinz Holliger

Auch jenseits dessen warten die Aufnahmen mit manch ungewohnter Erfahrung auf. Die vierte Sinfonie, d-moll, lässt sich in der gewohnten Version von 1851 wie in der kaum je gespielten Erstfassung von 1841 hören.Mehr lesen

Thüringen Kulturspiegel | Mai 2016 | Dr. Eberhard Kneipel | 1. Mai 2016

AIte Schönheit - neuer Glanz

Die Gesamtaufnahme von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken beim Edel-Label audite

Erster Anlauf, erstaunliche Experimente, imponierende Meisterwerke: Ein außergewöhnliches und an Entdeckungen reiches Hör-Erlebnis ist zu haben – auch dank audite!Mehr lesen

Stuttgarter Zeitung | 22.03.2016 | Dr. Uwe Schweikert | 22. März 2016

Eine Großtat für Robert Schumann

Heinz Holliger und das WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln nehmen das gesamte sinfonische Werk auf

Man sagt wohl nicht zu viel, wenn man diese CDs als die wichtigste Schumann-Einspielung seit langem rühmt. Sie beweist, dass es keines historischen Instrumentariums und auch keines Spezialistenensembles bedarf, um die Werke aus dem Geist der Zeit für heute aufs Neue zu verlebendigen.Mehr lesen

www.opusklassiek.nl | mei 2015 | Siebe Riedstra | 1. Mai 2015

De Zwitserse hoboïst, componist en dirigent Heinz Holliger heeft zich in al zijn disciplines intensief met het werk van Schumann beziggehouden. Als componist leidde dat tot verassende resultaten, getuige zijn Romancendres (hier besproken door Aart van der Wal). Als dirigent munt Holliger in de eerste plaats uit door een buitengewoon scherp en precies gehoor, tot op de Herz nauwkeurig. Zijn slagtechniek sluit niet naadloos aan op die precisie, en dat hoor je bijvoorbeeld in de wat rommelige start van de Eerste symfonie. Mehr lesen

Schumann-Journal | Nr. 4 / Frühjahr 2015 | Jan Ritterstaedt | 1. April 2015

Die Folgen 2 und 3 der neuen Gesamteinspielung sämtlicher sinfonischer Werke Robert Schumanns setzt die mit der ersten CD begonnene Interpretationslinie konsequent fort. Hier entsteht eine Reihe von Aufnahmen, die einen sicherlich sehr individuellen, in gewisser Weise auch modernen, vor allem aber künstlerisch sehr wertvollen Beitrag zur Schumann- Diskografie leistet. Man darf jetzt schon auf das nächste Produkt dieser Serie gespannt sein!Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | April 2015 | David W Moore | 1. April 2015

This is Volume 3 of Schumann’s complete Symphonic Works on Audite. <br /> These two works make a nice combination, since they share a formal structureMehr lesen

These two works make a nice combination, since they share a formal structure that connects the movements in a subtle and satisfying way. Both are in minor keys and share a depth of feeling that make them two favorites of mine.

These performances are not the grandest I have heard. Shevlin is a fine cellist, principal in this orchestra since 1998. He gives a friendly, sensitive reading of this great concerto. Holliger conducts that and the symphony with style, taking all the repeats in the symphony. I sometimes wish that both works were treated with a little more grandeur, but they are richly recorded.

These two works make a nice combination, since they share a formal structure

Fanfare | 26.03.2015 | Steven Kruger | 26. März 2015

I wish I could be more enthusiastic about these performances. But I’m afraid sympathy is in order—for the continuing tendency of German orchestrasMehr lesen

About a year ago, I had more favorable things to say about Heinz Holliger’s CD of the “Spring” Symphony and early version of the Fourth. He seemed to bring a joyous bounce to the fanfares in the young work, and his foreshortening of things went well with notions of impetuous ardor. Similarly, the early Fourth, whose holes in orchestration are the aural equivalent of Swiss cheese, benefitted from a tight and virtuosic zest, clipping virtually everything to its benefit. It sounded demoted to piano suite status—but brought off well. Small consolation for admirers of original versions….

The CD here records the 1850 revision and expansion of the score. Schumann’s reworking fleshes out all the gaps which existed earlier and encourages grand, blazing, and sweeping phrases. In the right performance, the work lands nearly within reach of the Brahms Second Symphony in terms of impact—27 years before the fact. But in the wrong hands?

The performance here is perversely scrawny and metallic on top, tubby on the bottom from an uninspired timpanist, and discombobulated beyond prediction. Every phrase is too short, in a sort of Baroque manner, except for the ones which should be short. Every syncopation seems to have its own syncopation. And worse, there is considerable energy, only it never soars. Such electricity as there is, is wasted on aggression. It is like being rabbit-punched by Handel.

One of the persistent and poorly supported ideas about the Mendelssohn/Schumann era is the notion that these composers only experienced small orchestras. Even if this were true, it wouldn’t mean composers were necessarily happy with the resources before them. Schumann and Mendelssohn were friends and participated in numerous music festivals together during the 1840s. I don’t imagine the early music purists like to be reminded that the orchestras were enormous. The premieres of Paulus and Elijah had orchestras of 176 and 172 musicians respectively. Berlioz managed to conduct the Fantastique at the Crystal Palace with 150 (and his score demands 250). I cannot quote similar chapter and verse about Schumann, but he was well aware that music was getting really “big” and probably had conducted his own symphonies with large orchestras.

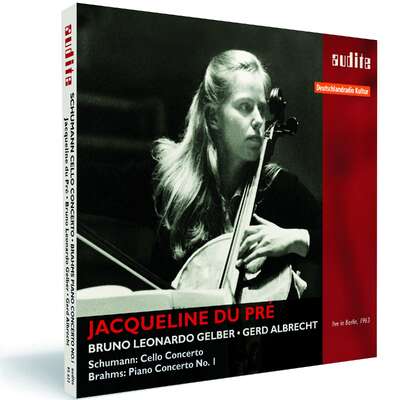

I shouldn’t fail to mention the cello concerto, the other late work included on this CD. It is always fascinating structurally, demonstrating how powerful an example the influence of Mendelssohn, in general and his violin concerto, in particular, had been. One could argue, though, that the themes are not so memorable as they should be, nor the textures sufficiently varied. Without the lively finale, the piece would languish away from the repertory. I refreshed my ears for this review with the Jacqueline du Pré performance and was struck by how alive, beautiful, and somehow sweepingly “upward” her phrasing manner always was. Oren Shevlin is the principal cellist of the Cologne orchestra and an accurate and musicianly player. But his manner is far too even. It doesn’t help that the orchestra avoids vibrato. This is the Schumann Concerto on Sominex.

I cannot really recommend the CD, despite good sound and scholarly notes. Schumann’s music is surely somewhere to be found between Handel’s Water Music and the Delius Cello Concerto. But Holliger’s HIP divining rod didn’t work.

Gramophone | March 2015 | Philip Clark | 17. März 2015

Music that grapples with demons and is never wholly at ease, even when wings bless the darkness with glimpses of light—when you’re RobertMehr lesen

The symphonic models are clear and we hear the ghostly spectre of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn—but no one has told Schumann’s material that it needs to conform, and the music cannot help but spill over any frame its composer attempts to place around it. The first movement of his Symphony No 1 reaches an apparent cathartic end-point as a solo flute line marked dolce reconciles grinding harmonic and structural inner tensions. Time to stop this madness. But then brass, percussion and trilling woodwinds unleash a stampeding burlesque march. Baleful chromatic inclines smudge the harmony, like Offenbach or Sousa turned on their dark side, and such instability derives from the restlessness of Schumann’s mind, you think, rather than being an overtly conceptual compositional strategy. The free jazz of the Second Symphony’s sostenuto assai prologue, C major credentials asserted by having the strings play anything but, as the brass sustain pure C major triads; in the Third Symphony, that extra movement that sneaks in before the finale, a cobwebby and gothic reimagining of the grounding contrapuntal principles of Renaissance music and Bach; and the audacious cyclic structure of the Fourth Symphony, each movement played attacca and dovetailing into the next. This music of demons and angels grapples also with angles—to take on structure, awkward punctuation, Schumann pushing form, his personal mission being to remould the symphony. And when the realisation dawns that Schumann composed the first version of what would become his Fourth Symphony in the same year as his First Symphony, eyes blink in astonishment. The natural order of things would be to presume that Schumann’s streamlined Fourth Symphony is a perfect distillation of the first three symphonies—but the pathway through Schumann’s symphonic journey is filled with unexpected and improbable twists and turns.

Deciding to record a cycle of the Schumann symphonies begs the question: what exactly should be recorded? And complementary but divergent ideas about the Schumann symphonies have been paraded as rarely before, with four major conductors during the past 18 months releasing four major cycles on disc. Sir Simon Rattle, with the Berlin Philharmonic, gives us four symphonies with the early 1841 version of the Fourth, while Yannick Nézet-Séguin (and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe) and Robin Ticciati (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra) opt for Schumann’s 1851 revised version. But Heinz Holliger and the WDR Symphony Orchestra of Cologne—like Sir John Eliot Gardiner and his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, whose trailblazing 1997 Schumann cycle was given the boxed-up DG reissue treatment last year—perceive Schumann’s symphonic evolution in seven stages. When Holliger completes his cycle during the next year and a half, Schumann’s early Symphony in G minor (the Zwickau Symphony) will take its place alongside the first three canonic symphonies, both versions of the Fourth, and the oftenoverlooked mini-me symphony Overture, Scherzo and Finale—Schumann’s compositional twists of fate put into historical context by a composer/conductor/oboist who has been obsessed with the composer’s enigma for more than 40 years.

I made Rattle’s cycle my Critics’ Choice album of the year in the December 2014 issue; I’ve also elevated Nézet-Séguin’s to an equivalent position in the past. Ticciati’s set has given me much pleasure too, and even more to think about. Nézet-Séguin and Ticciati deploy chamber-orchestra string sections, with Ticciati most explicitly evoking period-instrument practice. Rattle’s Berlin set carries its weightier orchestral ballast very elegantly, and his set became my portal back to Schumann after a longer period than I care to admit when my listening had been dominated by Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Rattle’s opulent, rapacious approach—the climax of the First Symphony’s opening movement and the Trio in the Second Symphony’s Scherzo seemingly moving faster than time itself, while the Berlin strings float the slow movement towards heaven—represented the warmest welcome back possible to Schumann’s dream-built chimeric fantasy world, the heartfelt directness of his melodic fancy played out over structural chess moves. Ticciati’s sometimes manically driven, flintier orchestral sound can be unexpectedly austere; Nézet-Séguin’s cycle is the most unashamedly Romantic of the four, fevered-brow gesturing, rubato with attitude.

Despite their differences, though, the sets are unified by one underlying common denominator—none of them could have been recorded 30, or even 20, years ago. Over the phone from his home in Zurich, Heinz Holliger suppresses a laugh when I ask: why now? Why, suddenly, have maestros gone all Schumann crazy? ‘Well, I started conducting him 30 years ago, when too many conductors had problems with Schumann,’ he reflects. ‘He was never a problem for pianists or composers—Debussy and Berg held him in great esteem—but conductors realised that you cannot try to sight-read Schumann; if you do, the music is completely grey.’ And even 50 shades of grey would not be enough to express Schumann’s multiverse of colour? ‘He does not write out everything; he doesn’t tell you which voice is the principal and which accompanies; nor whether one instrument should have a diminuendo while the others crescendo. To make a Schumann symphony sound light and transparent, as he intended, takes a lot of rehearsal. Each player needs to know whether they’re playing part of only the harmony, or whether they are involved in the counterpoint. Schumann was a great writer of words too, and you need to understand how close the phrasing is to speech. But many conductors are not so interested in this background; they just play what they read.’

Holliger reminds me that Schumann never heard more than 12 first violins during his whole life and, in his view, the period-instrument movement has had a very positive effect on how conductors perceive appropriate orchestral weighting and internal balance. And when I talk to Sir Simon Rattle a few weeks earlier, he makes a characteristically smart analogy: ‘We think of Beethoven and Brahms as being the grizzled old lions of Austro-German symphonic tradition,’ he tells me, ‘but Schumann’s symphonies move like a panther. Beethoven plunges his feet forcefully through the ground; but Schumann’s feet sprint and never fully touch the floor.’

Rattle can’t quite explain why Schumann is suddenly so de rigueur, although sometimes, he says, mysterious forces collude to raise the collective consciousness around a particular composer. But the important thing for Rattle is that distinct and informed conductorly perspectives must all be celebrated. Ticciati’s way is not his way, but Rattle admires enormously how he tackles the 1851 revision of the Fourth Symphony: ‘Robin makes a clear case for how the revised version can retain the radical edge of the 1841 version. Still it sounds like a fireball and I take my hat off to him.’

Which Fourth Symphony? That’s the most fundamental decision any wannabe Schumann conductor must make. To programme the 1841 version is to agree with Brahms, who owned the autograph score and wrote: ‘It is a real pleasure to see anything so bright and spontaneous expressed with corresponding ease and grace.’ He found the revised version charmless and stodgy, and Rattle and Holliger concur with Brahms, and each other, that the first version is much preferable—although they choose to do notably different things with that information. ‘Schumann made the revised piece in a depressive state,’ Rattle says, ‘and Brahms was completely right about the relative merits of the two versions.’ Holliger adds that Schumann’s orchestra in Düsseldorf, which premiered the new version, was nowhere near as honed as the standard of playing he had become accustomed to in Leipzig, while Schumann himself ‘was heavier, and moved and spoke more slowly’. But the pertinent point for Holliger is that Schumann retained his high-velocity metronome marks. Rattle chooses to ignore the later rewrite—Holliger gives us both but attempts to play the 1851 version, as he says, ‘retaining the true spirit of the earlier version’.

Holliger reminds me that he met Rattle 40 years ago when the young conductor invited him to perform Richard Strauss’s Oboe Concerto with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. And Rattle clearly remains in awe of Holliger’s status as a Schumann guru—‘Ask Heinz, when you speak to him, to tell you about the tempo relationships in the symphonies and about his extraordinary discovery in the fourth movement of the Rhenish Symphony.’ And I’m happy to take my cue from the Music Director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

On paper, and in the mind, Schumann’s Second Symphony registers as the most conventionally ‘symphonic’, its four movement groundplan—with a slow introduction breaking into an Allegro trot—putting you in mind of the first two Beethoven symphonies or of Haydn. And as I began to reacquaint myself with Schumann’s symphonic world, I pondered how a composition that felt instinctively unified melodically and motivically could also sound so disparate and varied, like each movement acting as a standalone character piece (not that you would necessarily want that). Holliger provides an answer.

‘The first and second movements,’ he tells me, ‘have the same metronome mark of crotchet=144, and the slow movement is nearly half; then the finale is in a very fast one-beat-per-bar, but still you feel like each bar matches the beat of the slow movement. The whole symphony is in one, like the conception of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony.’ Holliger explains how the music is glued together throughout by a four-note cell, but I ask him to tell me about the music’s disunity. Am I right to hear each movement orbiting independently too, in a way that is uniquely Schumann? Holliger alludes to Bernd Alois Zimmermann, the composer of Die Soldaten, Photoptosis and Requiem für einen jungen Dichter, who died in 1970, and who was famous for pieces that made liberal use of collage and knitted together layers of borrowed material. ‘He was fascinated by the idea of Kugelgestalt—that time is like a ball, and all times of all centuries are focused in one single point. I think Schumann understood this too. You ask about the Second Symphony—well, the beginning could be like 17thcentury polyphony and then, suddenly, it looks 120 years or more into the future. You feel this composer knows the whole history of music.’

The Second Symphony’s Scherzo has something of the lightness of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Holliger explains as he tells me about those angels and demons, ‘but is relentless, a diabolic dance, in the mood of ETA Hoffmann’. And that shockingly abrupt change of mood, the solo flute overtaken by a brutal march as the first movement of the First Symphony reaches its climax, is another characteristic Schumann moment. ‘In the First Symphony the flute symbolises a butterfly which here is overwhelmed by very tragic music. Marches are a frightening thing. Send soldiers to kill, and you’re asking them to stop thinking about what they are doing. Trills in Schumann, like the woodwind trills you mention, often tremor and shiver like music with a high fever—this is not the Baroque idea of a trill as ornamentation.’

Holliger talks about the symbolism of instrumental identity in Schumann’s music. In Overture, Scherzo and Finale a choir of three trombones appear suddenly like a premonition of the role they will take in the fourth movement of the Rhenish. ‘When his brother Eduard was dying, Schumann woke up at three in the morning. He had been dreaming about three trombones, and later he learnt that his brother had died at 3am. Always in Schumann, three trombones is a message about death.’ I mention that Rattle urged me to ask him about this same movement. ‘Well, when I looked at the sketches, I realised that the tempo changes to double the speed two beats later than in the printed score—nobody ever does this, but the difference is essential.’

That Schumann had such specific ideas about orchestral colour and instrumental identity runs triumphantly contrary to that tired cliché about his orchestration being somehow inept and clumsy. In the September 2014 issue of Gramophone, Robin Ticciati revealed that, for him, the attraction of Schumann is precisely because the orchestration is so, as he put it, ‘crazy’. ‘It’s also so controlled, and the palette is extraordinary. And I think when you get to a Schumann score, the first reaction is not to go, “What is all that?” but “What does he want?” and “What’s important here?”’ Ticciati hears clues about how Schumann ought to sound orchestrally in how he ‘orchestrates’ his piano music; and in the booklet-notes accompanying his cycle, Yannick NézetSéguin discusses how the defined attack and decay of modern trumpets help balance the orchestration.

And so Schumann wins. The consensus, circa 2014/15, is leave well alone. ‘Schumann learnt lots about orchestration from Mendelssohn, the greatest orchestrator of his time,’ Holliger explains, ‘and he tried to have a very transparent sound in the orchestra. It’s not that very heavy “German potato soup” sound. I never change a single note in any of the symphonies.’ Rattle confirms that Schumann must be ‘light and singing, or the sound can be too brittle—the key word is sostenuto.’ The impulsive and spontaneous side of Schumann is also important to Rattle. ‘The last symphonic music Schumann wrote was the Rhenish,’ he says, ‘and the fourth movement feels like Schumann falling apart, then the finale is an attempt to cradle him in a warm embrace. And for that to work, you can’t micromanage too heavily.’ Music to Schumann’s ears, I suspect—a composer who clearly knew the value of spontaneity: ‘My symphonies would have reached Opus 100 if I had but written them down,’ he said. ‘Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible to write anything.’

Image Hifi | 2/2015 | Heinz Gelking | 1. Februar 2015 Hörenswertes

Oren Shevlin spielt das Cello-Konzert eher lyrisch und versteht sich als Primus inter pares. Das wird mal eine sehr empfehlenswerte Gesamtaufnahme.Mehr lesen

International Record Review | February 2015 | John Warrack | 1. Februar 2015

With this third volume completing Audite's cycle of Schumann's symphonic works, Heinz Holliger couples the Cello Concerto to the revised version ofMehr lesen

It is still not an easy work to perform, and Holliger does admirably here, not only in seeing to it that details of orchestration are made clear but that the virtually singlemovement form, cyclic in its use of repeated main material, works well. He is also entirely justified in being flexible with tempos. Not only is this in keeping with the approach to tempo defended by most mid-nineteenth century German composer-conductors, Weber and Wagner prime among them, with this symphony it can help to express the overall form more lucidly. The Romanze in particular is most beautifully played (though the violin solo is surprisingly reticent); but Holliger also keeps the orchestra well balanced and lively in the outer movements, or rather sections, of the work. At the same time, he successfully moves the music across from the brooding opening to the strong, affirmative ending. The Cello Concerto is a much more problematic piece, also difficult to bring off. Oren Shevlin does well with the many passages when the cello is bustling away rather unrewardingly against the orchestra; he is clearly relieved to reach the central Langsam, when Schumann is much more recognizably himself with a song-like movement in which his own melodic genius as well as the powers of the cello are more freely released.

http://theclassicalreviewer.blogspot.de | Monday, 5 January 2015 | Bruce Reader | 5. Januar 2015 Cellist Oren Shevlin joins Heinz Holliger and the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln to provide a very fine Volume 3 of Audite’s series of the Complete Symphonic Works of Robert Schumann

The previous two volumes in this series have proved to be most impressive, putting this series on track to be one of the finest available. [...] Oren Shevlin matches the orchestra’s sensitive entry bringing a lovely tone, full of feeling, rich and mellow. He provides a deep thoughtfulness together with a fine technique. [...] This is certainly amongst the finest performances of this concerto on record.Mehr lesen

hifi & records | 1/2015 | Uwe Steiner | 1. Januar 2015

Wie in den vorausgegangenen beiden groß gelungenen Folgen lichtet Holliger den Orchestersatz auf und betont durch kongeniale, oft überraschende Detailarbeit den leidenschaftlichen Charakter dieser Musik. Der große Bogen der Vierten bleibt dabei stets gewahrt, vor allem ergeben die Stimmverdopplungen der Neuorchestration ihren klanglichen Sinn. In Oren Shevlin findet er einen kongenialen Solisten, der dem Cello-Konzert die nötige lyrische Versenkung und Melancholie gewährt.Mehr lesen

Record Geijutsu | 2015.1 | 1. Januar 2015

japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Fono Forum | Dezember 2014 | Thomas Schulz | 1. Dezember 2014 Entspannt und transparent

Die Musik Robert Schumanns spielt eine entscheidende Rolle im Kosmos Heinz Holligers. Immer wieder hat sich Holliger in seinen Kompositionen konkretMehr lesen

Die tiefe Verbundenheit des Oboisten, Komponisten und Dirigenten mit der Schumann'schen Tonsprache zeigt sich in einer angenehm entspannten, unaufgeregten Art und Weise. Ohne dass Holliger auf Temporekorde oder ein betont aufgerautes Klangbild aus ist, schafft er es, Vorurteile über Schumanns angeblich so ungeschickte Orchestrierungen sozusagen aus dem Handgelenk heraus vom Tisch zu wischen. Die Mehrsätzigkeit innerhalb eines quasi einsätzigen Satzgebildes, wie sie die Zweitfassung der vierten Sinfonie prägt, realisiert Holliger mit imponierender formaler Übersicht, und es zeigt sich zudem, dass zur Schaffung eines transparenten Klangbildes nicht unbedingt ein Originalklang-Ensemble zu nötig ist.

Passend dazu erklingt das Cellokonzert – mit Oren Shevlin – als vorwiegend lyrische Komposition, in der die Solostimme mit feinem Ton und unaufdringlicher Virtuosität gestaltet ist. Schumanns sinfonisches Schaffen hat in letzter Zeit viele Neueinspielungen erlebt, doch der Holliger-Zyklus dürfte einen der vorderen Ränge einnehmen.

BBC Music Magazine | Christmas 2014 | JH | 1. Dezember 2014

An intimate account of the Cello Concerto from Oren Shevlin is tellingly offset by the Fourth Symphony’s high drama, meticulously paced by HeinzMehr lesen

Gramophone | December 2014 | Rob Cowan | 1. Dezember 2014

The Mantovani-style fanned chords at the start of Arthur H Lilienthal's all-strings rewrite of the Cello Concerto does not augur well, though RaphaelMehr lesen

Most of Wallfisch's Schumann extras with piano are nicely done, the Fünf Stücke im Volkston delivered in the main with a light touch both by Wallfisch and by his fine pianist John York, the Three Romances, Op 94, and the Op 73 Fantasy Pieces similarly eloquent in a relaxed, unassuming way (barring the fiery last movement of Op 73), the Adagio and Allegro, Op 70, in many respects the disc's highlight. I wasn't too keen on the two Lieder transcriptions (both taken from the Op 39 Liederkreis collection), certainly not the start of 'Mondnacht', where the cello's presence spoils the music's solitary atmosphere, and in 'Frühlingsnacht', where the soloist ideally needs to project with greater presence.

Holliger's account of the 1851 Fourth Symphony has all the qualities that make his accompaniment to the Cello Concerto so distinctive, namely flow, transparency, and character (note the subtle but dramatic diminuendo among the horns at 4'42"). The expressive Romanze follows close on the heels of the first movement, surely as it should, the Scherzo asserts a virile presence, while the fast-paced finale is breezy and exhilarating, with plenty of light and shade. Altogether a worthy continuation of Holliger's Schumann series, with excellent playing and well-balanced sound.

BBC Music Magazine | December 2014 | CD | 1. Dezember 2014

These are light and airy performances, with Oren Shevlin a poignant and intensely lyrical soloist in the Cello Concerto, while Holliger's pacing ofMehr lesen

www.classicalsource.com | December 2014 | Antony Hodgson | 1. Dezember 2014 Heinz Holliger conducts Robert Schumann’s Complete Symphonic Works – Volume 3, Cello Concerto (with Oren Shevlin) & Revised Fourth Symphony

The immensely thorough booklet note clarifies the nature of both works veryMehr lesen

Musik & Theater | 11/12 November/Dezember 2014 | Reinmar Wagner | 1. November 2014 Delikater Klang

Vor allem im Konzert, das der Brite Oren Shevlin hellwach und klanglich delikat, im Mittelsatz wunderschön innig spielt, zeigen sich Orchester, Dirigent und eben Solist von herausragender Souveränität und von vielschichtig ausgeformter interpretatorischer Durchdringung.Mehr lesen

www.artalinna.com | 23 octobre 2014 | Jean-Charles Hoffelé | 23. Oktober 2014 L’orchestre réinventé

Soudain l’orchestre se creuse, les accords claquent, le geste devient péremptoire : on le comprend, Schumann symphoniste s’est trouvé. Les pupitres de la WDR peuvent chanter autant qu’ils le veulent, Holliger les accompagne d’un geste enthousiaste, presque avec ivresse.Mehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 29/09/2014 | Remy Franck | 29. September 2014 Beseelte Ausdruckskraft

Diese CD mit dem Violoncellokonzert und der zweiten Fassung der d-Moll-Symphonie ist die m.E. bislang attraktivste aus der Holliger-Gesamtaufnahme.Mehr lesen

Besides a very lively Fourth Symphony in its second version, this CD contains an absolutely fascinating performance of the Cello Concerto. Oren Shevlin, the Fist Cellist of the WDR Orchestra, plays with great delicacy and tenderness, affectionate beauty, thus giving the music an overwhelmingly intimate character.

Stereo | 12/2014 Dezember | Thomas Schulz

Schumanns sinfonisches Schaffen hat in letzter Zeit viele Neueinspielungen erlebt, doch der Holliger-Zyklus dürfte, wenn er beendet ist, einen der vorderen Ränge einnehmen.Mehr lesen