Auto-Rip

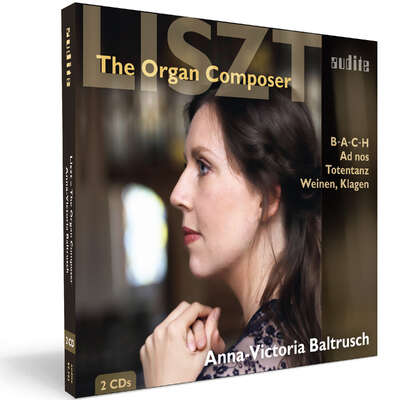

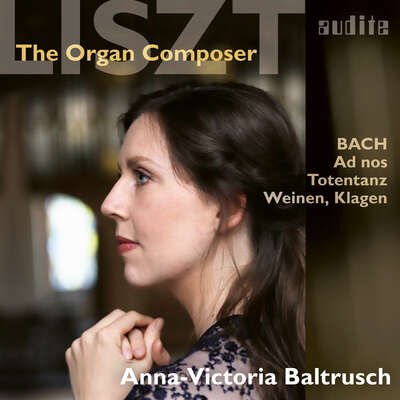

Innovation, colour, virtuosity, spirituality, precipice, transcendence – these are the most important poles explored by organist Anna-Victoria Baltrusch in Liszt’s organ works. Her own adaptation of Liszt’s diabolical Totentanz is a stirring highlight of her CD.more

"Die allen Schwierigkeiten [...] mühelos gewachsene Organistin setzt die Vielfalt der Register an beiden Instrumenten souverän ein." (Musica Sacra)

Track List

This bonus track is only available as a download!

Details

| Liszt - The Organ Composer | |

| article number: | 97.793 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143977939 |

| price group: | BCE |

| release date: | 7. October 2022 |

| total time: | 86 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

Liszt was a constant musical seeker and researcher: many formal and harmonic innovations of the romantic era can be traced back to him. His three main organ works contributed significantly to the re-evaluation of nineteenth century organ music. Liszt struggled to find ideal formats for them, and also arranged numerous works, penned by him as well as by other composers, for the organ, which for him represented the logical link between the piano and the orchestra. On this CD, the organist Anna-Victoria Baltrusch draws on the evolving nature of his organ music by combining Liszt's three great organ works with her own highly virtuosic adaptation of his Totentanz (Danse macabre) - originally written in versions for piano and orchestra, two pianos, or piano alone.

Reviews

Diapason | N° 734 JUIN 2024 | Paul De Louit | June 1, 2024

On peut soupçonner l’album d’être construit autour de la » Totentanz « transportée à l’orgue par Anna-Victoria Baltrusch. Tour de forceMehr lesen

Moins plaisantes sont les trois pièces canoniques, présentées comme des showpieces de pure virtuosité, dans lesquelles les mêmes effets d’orchestration se retrouvent avec moins d’à-propos, assortis de contrastes faciles et de rubatos téléphonés. On pourra éventuellement dire que le décousu de » B.A.C.H. « renoue avec l’esprit rhapsodique de l’improvisation que fut sans doute, à l’origine, ce prélude et fugue si peu diptyque ; en revanche, il est difficile de justifier l’atomisation de la forme d’» Ad nos « et surtout de » Weinen, Klagen « en un défilé de clichés techniquement étincelants (sauf les fugues d’» Ad nos «, étonnamment dénervées) mais d’où toute poésie est radicalement bannie.

Pour rendre leur musique à ces trois chefs-d’œuvre, vous avez l’embarras du choix : la virtuosité de Pierre Labric (Solstice), l’intelligence analytique de Jean-Pierre Leguay (Festivo) ou bien le romantisme altier de Louis Robilliard (Festivo) sans oublier, pour » Ad nos «, le retour aux sources d’Yves Rechsteiner (Alpha) sur le somptueux Ladegast de Schwerin.

Musica Sacra | Jg. 144, Nr. 1 Februar 2024 | Herbert Glossner | February 1, 2024

Die allen Schwierigkeiten [...] mühelos gewachsene Organistin setzt die Vielfalt der Register an beiden Instrumenten souverän ein.Mehr lesen

Crescendo Magazine | Le 20 novembre 2023 | November 20, 2023 | source: https://www.cres... Les Millésimes 2023 de Crescendo Magazine

Crescendo Magazine est heureux de vous présenter la sélection de ses Millésimes 2023. Un panorama en 12 albums et DVD qui vous propose le meilleurMehr lesen

Entre novembre 2022 et novembre 2023, Crescendo Magazine a publié près de 540 critiques d’enregistrements audio, déclinés en formats physiques et numériques ou en DVD et Blu-Ray. Depuis un an, nous avons décerné une belle centaine de Jokers, qu’ils soient déclinés en “absolu”, “découverte” ou ‘patrimoine”. Les millésimes représentent donc le meilleur du meilleur pour la rédaction de Crescendo Magazine. […]

Du côté des claviers, on pointe un exceptionnel album Debussy par le jeune pianiste Jean-Paul Gasparian (Naïve), un récital d’orgue consacré à Liszt par Anna-Victoria Baltrusch (Audite) et surtout ce superbe coffret Warner en hommage à notre cher Nicholas Angelich, tel une boîte aux trésors qui fascine à chaque audition.

La Tribune de l'Orgue | 75/3 Septembre 2023 | September 1, 2023 LISZT ET D'AUTRES, PAR ANNA-VICTORIA BALTRUSCH

Les qualités de l'interprète ressortent presque mieux que lorsqu'elle s'attaque à Liszt: on voit bien d'où elle sort et où elle a été formée: une toute bonne musique [...] Mehr lesen

Crescendo Magazine | 10 juillet 2023 | Christophe Steyne | July 10, 2023 | source: https://www.cres...

JOKER ABSOLU

Magistral programme lisztien sur le colosse de la Hofkirche de Lucerne

Outre ses vertus techniques, l’organiste n’est pas en manque d’imagination, puisqu’elle nous livre son propre arrangement de la Totentanz, élaboré à partir de la version pour deux pianos S. 652 dérivée de l’original concertant S. 126. [...] Même si la discographie abonde pour les trois autres œuvres au programme, voilà qui confirme l’attrait de ce parcours lisztien parmi les plus sains et captivants.Mehr lesen

Gramophone | Tuesday, January 10, 2023 | Jeremy Nicholas | January 10, 2023 | source: https://www.gram...

Liszt's Totentanz: a guide to the best recordings

Franz Liszt’s scintillating journey to the Underworld challenges pianists and thrills audiences. Jeremy Nicholas compares a selection of recordings of this diabolic masterpiece and selects his favourite

Pisa’s Piazza dei Miracoli, also known as the Piazza del Duomo, contains the Cathedral, the Baptistry, the Campanile (aka the Leaning Tower) – andMehr lesen

The couple had eloped in 1835, leaving Paris for Geneva and thence, for the next few years, travelling through Switzerland and Italy absorbing scenery, places, literature and painting, while producing three illegitimate children. The first of these was their daughter Cosima, later to become the wife of Hans von Bülow and latterly of Richard Wagner. From this period of Liszt’s prolific output came early versions of the 12 Transcendental Études, the Six Études de Paganini and the first two volumes of Années de pèlerinage, and much else besides. Totentanz, a series of variations on the Latin plainsong chant of the ‘Dies irae’, can be considered ‘the spiritual sister’ of these ‘Years of Travel’ (indeed, Variation 5 puts one in mind of the central section of the Dante Sonata).

The gestation of Totentanz was protracted and complex. Without going into great detail, basically there exist two versions: the first, dated October 21, 1849, with the title Fantasie für Pianoforte und Orchester was not published until 1919 (in an edition by Busoni); it is generally known as the ‘De profundis’ version because it incorporates the plainsong setting of Psalm 130 (‘Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, O Lord’).

Liszt continued tinkering with the score between 1853 and 1859, when a second version appeared. This dispenses with all of the ‘De profundis’ material and other sections never sanctioned for publication by the composer. It was issued with the title Todtentanz [sic] (Danse macabre) – Paraphrase über ‘Dies irae’, and published in 1865, the same year in which Liszt’s versions for solo piano and two pianos were published. It was dedicated to his son-in-law Hans von Bülow and it was he who gave the first performance of this version on April 15, 1865, in The Hague with an orchestra conducted by the Dutch composer Johannes Verhulst. Though there are several other editions, notably by Liszt pupils Alexander Siloti, Bernhard Stavenhagen and Eugen d’Albert, it is Liszt’s second version that is most frequently heard today,

Liszt was not the first – and by no means the last – to use the ‘Dies irae’ (‘Day of Wrath’, used for centuries in the Roman Catholic rite of the Mass for the Dead). Berlioz quotes it in his Symphonie fantastique (1830), the premiere of which was attended by Liszt. The music is a sequence of variations on the theme, interspersed with three cadenzas, a development section and a coda. Only the first five variations are so numbered in the score but it is possible to identify over 30 different treatments of the theme (or part of the theme) by the piano or other instruments in the course of the work, often variants within the variations.

This survey is concerned principally with the second version. Why? Despite the two versions having many sections in common, they are two distinct and different works. Version 2 represents Liszt’s final, definitive thoughts (ie he decided his intentions were better realised by cutting the ‘De profundis’ material) to form, in this writer’s opinion, a tone poem that expresses itself more powerfully with greater economical means.

[…]

The version for solo piano is also the basis for its adaptation as a work for organ, an instrument to which Totentanz is particularly well suited. There’s a new recording of it, this one based on the two-piano arrangement, made and played by Anna‑Victoria Baltrusch (reviewed on page 71). It’s impressive enough but not the equal of the quite stunning performance by Thomas Mellan on the organ of the First United Methodist Church, San Diego (available to view on YouTube), one of several filmed accounts on the organ. This one, while properly thrilling, highlights the ‘Dies irae’ quotations more clearly than many accounts of the second piano-and-orchestra version, recordings to which it is now high time we turn.

www.ResMusica.com | Le 3 janvier 2023 | Frédéric Muñoz | January 3, 2023 | source: https://www.resm... Franz Liszt et l’orgue avec Anna-Victoria Baltrusch à Lucerne

C’est dans cette œuvre que l’interprète Anna-Victoria Baltrusch montre le plus ses qualités de grande virtuose et de musicienne très subtile dans le choix des jeux, des équilibres et du côté orchestral donné à ces pages. Par une grande musicalité, elle nous fait aimer Liszt organiste, alors que lui-même le fut assez peu, bien que grandement inspiré dans ces compositions.<br /> Voici une version qui fait partie désormais des références, sur un orgue exceptionnel de plus de 100 jeux et dans une prise de son très soignée.Mehr lesen

Voici une version qui fait partie désormais des références, sur un orgue exceptionnel de plus de 100 jeux et dans une prise de son très soignée.

Choir & Organ | January 2023 | Chris Bragg | January 1, 2023

Yet another Liszt recording? Yes indeed, although this survey of the large-scale organ works has, as a bonus, the performer’s own virtuosicMehr lesen

Gramophone | December 2022 | Jeremy Nicholas | December 1, 2022 | source: https://www.gram...

A good programme, this, with all three of Liszt’s major organ works and the addition of Totentanz in an arrangement by Anna-Victoria Baltrusch basedMehr lesen

Disc 1 (46'46") opens with the Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H, using the second of the two versions (1870 rather than 1855), following it with the mighty Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale Ad nos, ad salutarem undam. Inspired by a theme from Meyerbeer’s opera Le prophète, it is the organ equivalent of Liszt’s B minor Sonata, with which it has much in common: apart from their considerable demands on stamina and technique, both have a three-movements-in-one structure lasting roughly 30 minutes with reflective central sections in Liszt’s favourite spiritual key of F sharp major, closely followed by a fugue and virtuoso finale. On disc 2 (37'33") we have Totentanz and Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen.

There’s no doubting Baltrusch’s impressive technical facility. The recording captures the full sonority of the great organ of the Court Church, Lucerne, with its powerful 32ft Principal and three 16ft pedal stops growling away beneath to thrilling effect. Her registration choices for the softer central recitativo and adagio sections of Ad nos, where many organists like to make a contrast with disquieting nasal reeds, are agreeably concomitant with the boisterous outer sections. There’s one big problem. The church acoustic has a long decay and when fingers and feet are flying, detail is at a premium. It is certainly sonically awe-inspiring, but for long stretches – and especially if you do not have scores to follow – it is hard to know what is going on amid the amorphous cathedral rumble.

Textural clarity is less of a problem in Baltrusch’s own resourceful arrangement of Totentanz. Who can deny the pleasure of the ‘Dies irae’ theme thundered out fortissimo on the pedals? Yet the performance is too sectionalised to be completely successful. Over-long pauses between variations and an over-languid tempo for the canonic fourth variation contribute to an extra three minutes above the average performance time. Compared to the razor-sharp transcription and its malevolent, speaker-crunching performance by Thomas Mellan on the organ of the First United Methodist Church, San Diego (available to view on YouTube), Baltrusch is more thé dansant than danse macabre.

www.orgelnieuws.nl | 31. oktober 2022 | October 31, 2022 | source: https://www.orge...

Niederländische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Orgelportal

| 28. OKTOBER 2022 | Thomas Haubrich | October 28, 2022 | source: https://orgelpor...

Review der neuen Doppel-CD | CD des Monats Oktober 2022

Anna-Victoria Baltrusch an der Grossen Kuhn-Orgel der Hofkirche St. Leodegar Luzern

Anna-Victoria Baltrusch bietet mit dem vorliegenden Doppel-CD-Album die höchst willkommene Ergänzung ihres Liszt-Kompendiums, das sie mit derMehr lesen

Baltrusch nutzt diesen einzigartigen Klang-Kosmos mit feinsinnigem Gespür für Farben, Dramatik und Virtuosität kongenial aus. Als Repertoire dieser Doppel-CD hat sie sich nicht weniger als Liszts drei Grosswerke – „Präludium und Fuge über B-A-C-H“, die epochale „Fantasie und Fuge über „Ad nos ad salutarem undam“ und das Spätwerk „Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen“ – vorgenommen. Mit stupender Virtuosität und einer grossartigen Klangregie vermag die Interpretin all diesen drei orgelmusikalischen „Achttausendern“ gerecht zu werden, von denen jedes einzelne Werk schon eine tüchtige Herausforderung an Spieler, Hörer und Instrument darstellt.

Besonders hervorzuheben sind die grossen Spannungsbögen, die die Interpretin sowohl im „Ad nos“ wie auch im „B-A-C-H“ zu zeichnen vermag, damit der Gesamtzusammenhang des, sich in zahlreiche Unter-Ideen verästelnden Flusses nicht verloren geht. Interessanterweise nimmt sie beim Ersteren einige Stellen der Klavierfassungen Liszts mit hinein, was dem Ganzen sehr zugute kommt. Berührend etwa der mystische Mittelteil in der Prophetenfantasie; unmittelbar klanglich physisch „angreifend“ dagegen beispielsweise der Dialog der Fanfaren (Tuba mirabilis im Altarwerk gegen die grosse Orgel).

Für mich als „Höhepunkt“ der CD – wenn man dann eine grandiose Leistung überhaupt noch zu steigern vermag, ist ihre eigene Orgelfassung von Liszts „Totentanz“, einer zwölfteiligen Paraphrase über das „Dies irae“, die in ihrer Perfektion nur darauf hoffen lässt, dass die Interpretin ihre Transkription auch als Notenausgabe veröffentlichen wird – eine willkommene Bereicherung des Liszt-Repertoires und in der Wirkung quasi ein vollkommen genuines „Orgelstück“ – als sei es der Hoforgel und der Organistin auf den Leib geschrieben.

Fazit: eine der besten CD-Neuerscheinungen des Jahres 2022!