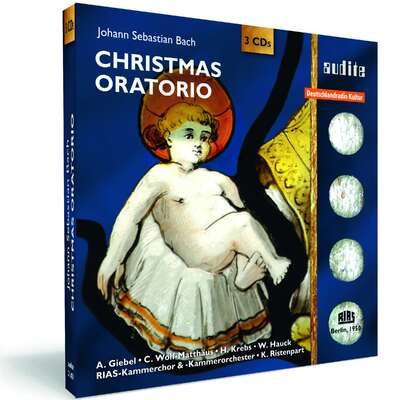

This complete recording of the “Christmas Oratorio” from 1950 presents the leading Bach singers of that time. Alongside the RIAS Chamber Choir and the RIAS Chamber Orchestra and under the direction of Karl Ristenpart, they created a recording which both embraces Bach interpretation of the time on a high level, and also heralds historically informed performance practice, particularly in Parts 4 and 5. After the war, Ristenpart championed a cultural ideal which turned away from the drive for monumentalism. In this, Bach served him as a catalyst for mental renewal and as a guide to turn away from the craze surrounding Wagner.more

This complete recording of the “Christmas Oratorio” from 1950 presents the leading Bach singers of that time. Alongside the RIAS Chamber Choir and the RIAS Chamber Orchestra and under the direction of Karl Ristenpart, they created a recording which both embraces Bach interpretation of the time on a high level, and also heralds historically informed performance practice, particularly in Parts 4 and 5. After the war, Ristenpart championed a cultural ideal which turned away from the drive for monumentalism. In this, Bach served him as a catalyst for mental renewal and as a guide to turn away from the craze surrounding Wagner.

Track List

Details

| Johann Sebastian Bach: Christmas Oratorio | |

| article number: | 21.421 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143214218 |

| price group: | CL |

| release date: | 1. November 2013 |

| total time: | 155 min. |

Bonus Material

- press kit Christmas Oratorio

-

Producer's Comment

First-hand impressions of producer Ludger Böckenhoff [German]

Informationen

Following the Bach cantatas edition with Karl Ristenpart, audite now continues the series of historic recordings from the archives of RIAS Berlin with a complete recording of the "Christmas Oratorio". As soloists, Ristenpart engaged leading Bach singers of the time, thus ensuring that the recitatives of the Evangelist, the arias and ensembles were of particularly high quality. Alongside the RIAS Chamber Choir and the RIAS Chamber Orchestra a recording was created in December 1950 which both validly represents Bach interpretation of that time, and also heralds, notably in Parts 4 and 5, historically informed performance practice. This release is furnished with a "producer's comment" by producer Ludger Böckenhoff. This CD forms part of our series "Legendary Recordings" and bears the stamp "1st Master Release". This term stands for the exceptional quality of audite's archive releases which are all, without exception, produced using original tapes from the radio archives. Usually, these are the original analogue tapes with tape speeds of up to 76 cm/s which are of astonishingly high quality, even by today's standards. In addition, the process of re-mastering - executed with professional expertise and sensitivity - reveals hitherto hidden details of the interpretations, creating a sonic image of superior quality. CD releases produced from private recordings of radio broadcasts or old 78rpm records cannot match this level of sound quality.

Karl Ristenpart responded to the accession to power by the Nazis in 1933 by retreating to working with chamber ensembles - a sphere which was able mostly to escape the cultural-political interference by the state authority. The Nazi nomenklatura felt that Wagner was the bringer of a new era; Ristenpart countered with Bach: Wagner's "Ring of the Nibelung" depicting the demise of Germanic gods and heroes was opposed by Ristenpart with the cantata cycle concerning the emergence of Christianity and its "Saviour" - the "Wagner Ring" vs. the "Bach Ring".

After the war, Ristenpart championed a cultural ideal which turned away from the drive for monumentalism. In this, Bach served him as a catalyst for mental renewal and as a guide to retreat from the craze surrounding Wagner. Ristenpart's decisions of the 1930s thus permeate his Bach interpretations in the cantatas as well as the "Christmas Oratorio" of 1950.

Reviews

klassik.com

| 06.03.2016 | Gustavo Martin Sanchez | March 6, 2016 | source: http://magazin.k...

Neubeginn mit Altbekanntem

Bach, Johann Sebastian – Weihnachtsoratorium

Dieses historische Tondokument von Bachs Weihnachtsoratorium ist einMehr lesen

Record Geijutsu | April 2014 | April 1, 2014

japanische Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

Das Orchester | 03/2014 | Rüdiger Krohn | March 1, 2014

Viele Entscheidungen dieser Einspielung erklären sich aus den Umständen ihrer Entstehung und ihrem Konzept. Einerseits ist sie (namentlich in den ersten drei Kantaten) in Teilen noch der zeittypischen Bach-Tradition verpflichtet, andererseits aber öffnet sie sich (vor allem in den weniger häufig aufgeführten und verfestigten Kantaten) einer moderneren Praxis. Das macht die Aufnahme [...] zu einem aufschlussreichen Tondokument des Übergangs.Mehr lesen

Fanfare | 06.02.2014 | George Chien | February 6, 2014

My first Karl Ristenpart review appeared way back in Fanfare 2:5, actually before the magazine adopted its current method of identifying back issues.Mehr lesen

Ristenpart was a player in the transition from the traditional reverential and monumental Bach that held sway during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to the tighter, lighter, and brighter idiom that prevails today. Case in point: He sang through the fermatas that mark the ends of phrases in Bach’s chorales. Rather than interpreting chorales as if they were miniature tone poems, he treated them more in the manner of congregational singing. His choruses, too, shed some of their massiveness. This Christmas Oratorio is, in a sense, an historical document. One can sense a change from the opening chorus of the first cantata to the later ones. Audite’s notes cast a revealing light on the situation. The recording was made in 1950, just five years after the end of the War. The RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) Chamber Chorus of Berlin was a relatively new organization, so Ristenpart started the sessions cautiously, gradually picking up his tempos as his singers became more comfortable with them. Another hint of things to come is Ristenpart’s reading of the famous pastoral Sinfonia in Cantata 2. It would be a surprise to me if Reinhard Goebel were to adopt Ristenpart’s breathless tempo. The soloists were among the best of their time; I was especially impressed by alto Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus, but all were excellent. I can’t recommend this set as a first Christmas Oratorio, but it’s a valuable document, worth preserving, and rewarding on its own terms.

Ristenpart did benefit from the innovative marketing efforts of the then new and active minor labels. Caught between the older traditions and changes yet to come, he isn’t well remembered today. He deserves better.

www.opusklassiek.nl | februari 2014 | Aart van der Wal | February 1, 2014

Het lijkt niet ver bezijden de waarheid dat in deze uitvoering de eerste drie cantates sterker aansluiten bij de traditionele ‘Bachpflege' dan de overige drie, die meer in het licht van de ‘nieuwe' tijd staan. Het is ronduit fascinerend die verschillen te horen en ze hun eigen plaats binnen het geheel te geven. Het oude en het nieuwe, verenigd in dit historische toondocument, levert absoluut nieuwe inzichten op.<br /> <br /> Tot slot nog iets over de cd-verdoeking. Er werd wederom met liefde en vakmanschap gerestaureerd, waardoor het RIAS-archief zomaar nieuwe dimensies krijgt toegeworpen. Als we al van het bestaan ervan wisten, of deels wisten, hadden we toch niet kunnen bevroeden dat al dit materiaal nu op zijn best aan ons wordt voorgesteld.Mehr lesen

Tot slot nog iets over de cd-verdoeking. Er werd wederom met liefde en vakmanschap gerestaureerd, waardoor het RIAS-archief zomaar nieuwe dimensies krijgt toegeworpen. Als we al van het bestaan ervan wisten, of deels wisten, hadden we toch niet kunnen bevroeden dat al dit materiaal nu op zijn best aan ons wordt voorgesteld.

ensuite Kulturmagazin | Nr. 133 | Januar 2014 | Francois Lilienfeld | January 1, 2014 Bach, wie man ihn sich öfters wünschte…

Eine Besprechung des Weihnachtsoratoriums im Januar? Nun ja, Verspätungen können vorkommen; vor Allem aber ist diese Musik so universell, dass manMehr lesen

Der Dirigent Karl Ristenpart (1900-1967) ist heute leider weit weniger bekannt als er es verdiente. Seine Karriere wurde durch die Machtübernahme der Nazis unterbrochen: Zu keinen Konzessionen bereit beschränkte er sich auf stille Arbeit mit Kammerorchestern, bis ihm auch dies verboten wurde und die Machthaber ihn, als Truppendirigent, zum Wehrdienst zwangen. Nach der Kapitulation wurde ihm, als Unbelasteten, sofort eine wichtige Arbeit übertragen: Er sollte Orchester und Kammerchor des RIAS (Radio im amerikanischen Sektor) Berlin aufbauen. Damit war er an der Spitze (zeitweise zusammen mit Ferenc Fricsay) eines der Rundfunkorchester, die von den Besatzungsmächten ins Leben gerufen wurden, und die einen ungeheuren musikalischen Aufschwung in Nachkriegsdeutschland ermöglichten. 1953 zog Ristenpart nach Saarbrücken, wo er das Kammerorchester des Saarländischen Rundfunks gründete.

Sein Repertoire war breit, besonders aber lagen ihm Bach und Mozart am Herzen; dazu Mahler, dessen Musik seine Entscheidung, Dirigent zu werden, stark beeinflusst hatte.

1949 begann der RIAS einen Bach-Kantatenzyklus mit Ristenpart aufzunehmen. Dieses Projekt – es hätte eine Gesamtaufnahme werden sollen – musste leider aus vertraglichen Gründen 1952 abgebrochen werden. Die 28 existierenden Kantaten hat die Firma audite 2012 herausgegeben (audite 21.415, 9 CDs). Vor kurzem nun veröffentlichte dieselbe Firma Bachs Weihnachtsoratorium mit Kammerchor, Knabenchor und Kammerorchester des RIAS (audite 21.421, 3 CDs). Das Dokument stammt vom Dezember 1950.

Die Aufnahme ist wohl eines der wichtigsten Zeugnisse der Bach-Interpretation. Ristenpart hat ein untrügliches Gefühl für die Klang- und Gefühlswelt des Thomaskantoren, aber auch für seinen Stil; dass einige Appoggiaturen fehlen und in da capo-Teilen nicht variiert wird, nimmt man in Kauf. Vor allem hervorzuheben ist sein Sinn für Tempi, die bei ihm nie verschleppt oder gehetzt wirken: Jedes Tempo ist dem entsprechenden Stück (und seinem Text) angepasst. Die Bass-Arie «Großer Herr und starker König» ist majestätisch, die sehr zügige Pastorale klingt nach freier Luft, der Chor «Herrscher des Himmels» ist wirklich ein Triumph-Psalm.

Die von Bach so herrlich zusammengestellten Klangkombinationen (Flöten, Oboen, Oboe d'amore…) kommen dank der hohen Qualität des Orchesters wunderbar zur Geltung. Und die Solisten gehören wohl zum Besten, was Deutschland 1950 zu bieten hatte: Agnes Giebel (Sopran), Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus (Alt), Helmut Krebs (Tenor), Walter Hauck (Bass). Auch die Chöre sind groß in Form; was ab und zu an Delicatesse fehlt, wird durch Sangesfreude mehr als wettgemacht!

Die Aufnahmequalität zeugt für das große technische Können der damaligen Toningenieure. Nur die Hörner im vierten Teil dürften etwas präsenter sein. Für die Überspielung auf CD wurden die Originalbänder benutzt, was einen weiteren Vorteil bedeutet.

Viel Wissenswertes über die Musikerpersönlichkeit Ristenparts und die Hintergründe der Aufnahme vermittelt der hochinteressante Text von Habakuk Traber im Beiheft.

Dass das ganze Werk (6 Kantaten!) in zwei Tagen aufgenommen wurde, ist nicht nur erstaunlich, sondern erklärt vielleicht auch die erfrischende Spontaneität der Aufführung.

Ein Teil der Chöre und Arien im Weihnachtsoratorium stammt übrigens aus weltlichen Kompositionen Bachs. Dieses «Parodieverfahren» war damals gang und gäbe und hat nichts Schockierendes; im Gegenteil, es zeigt die Größe des Komponisten, der Allgemeingültiges schafft. Oder, um einen berühmten Bach-Forscher zu zitieren: «Dennoch, oder vielleicht gerade, weil in diese Weihnachtsmusik ein so großer Teil ursprünglich weltlicher, d. h. volkstümlicher Weisen, Bachs eingeschmolzen ist, strahlt sie in so unvergänglicher Frische.» (Arnold Schering, 1922)

Schade, dass solch vollendetes Bach-Musizieren immer seltener zu hören ist – mit namhaften Ausnahmen natürlich...

International Record Review | December 2013 | Carl Rosman | December 1, 2013 Three Christmas Oratorios

'Tis the season to jauchzen and frohlocken. Right on cue, here is a stimulatingly diverse crop of Christmas Oratorios: two on rather different scalesMehr lesen

Ristenpart's 1950 account would not be an obvious choice as one's only Christmas Oratorio. It is nonetheless an intriguing document of post-war Bach performance practice, incorporating several ideas one would generally, associate with later decades. Even though it does run onto three CDs, the overall duration of 156 minutes is just four minutes longer than Layton's and ten more than Herreweghe's and some of his tempos are swifter than either.

Habakuk Traber's booklet note puts Ristenpart in historical context as helping to reclaim Bach from Nazi-era monumentality. The chorales show a quite modern understanding of Bach's fermatas (as phrase marks rather than held chords), making Layton's approach seem strangely old-fashioned by comparison. The shepherds' Sinfonia at the beginning of Part 2 is most attractively phrased and zips by in a mere 4'20" – Traber makes the comparison with René Jacobs's 1997 period-instrument recording featuring the successors of the same choir, in which the same Sinfonia takes a leisurely 7'48" (Harmonia Mundi HMC2901630.31). On the debit side, the large-scale choruses are generally (inevitably?) somewhat slower to modern ears, with the runs choppily articulated; the 3/8 choruses, of which there are many, do not always manage to phrase in one to the bar, instead emerging with three relatively even accents.

The solo arias often show an enviable degree of chamber-music rapport between voices and instruments – something which eludes the vast majority of performances, historical or otherwise. (Indeed the combination so often met with today of rigorously historical instruments and not particularly historical voices is all but guaranteed to miss this rapport which Bach's scores above all seem to demand.) In 'Frohe Hirten' Helmut Krebs's tenor and the unnamed flautist trade their demisemiquavers as equals; in 'Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben' Krebs is neatly embedded in the violin obbligatos. In 'FIößt, mein Heiland' soprano Agnes Giebel and her oboist are not only on compatible dynamic planes but share a compatible musical concept, which could not be said for the version on the Layton recording, as lovely as it is in other respects. The instrumental contribution is in general uneven: the high trumpets are overstretched in many passages compared with what their valveless colleagues manage so serenely on the other two recordings, the woodwinds generally fine, the strings a little inarticulate by today's standards, the harpsichord rather out of place in the general instrumental concept.

In all, though, Ristenpart's recording is an important testament to the complexity of interpretative currents in Bach performance in the second half of the twentieth century – not least in suggesting that some recent developments might not have led to more historically or musically appropriate results.

Not, then, the only recording to have on the shelf, but certainly one to be recommended for any listeners seriously interested in the recent history of performance practice. It is hard to avoid noticing that the vocal soloists on recent period-instrument recordings employ significantly more vibrato than some of their mid-twentieth century counterparts: not only Krebs for Ristenpart here but also, for example, Anton Dermota in Furtwängler's classic St Matthew Passion (EMI Références 5 65509-2) are comprehensively outdone in that department by Gilchrist and Hobbs, as well as Anthony Rolfe Johnson and Hans-Peter Blochwitz for Gardiner, Paul Agnew for Philip Pickett (Decca 458 838-2) and dozens of others. (Choirs, to be fair, have gone decisively in the opposite direction, and a good thing too – the RIAS choir's vibrato for Ristenpart is an unequivocal debit point.) Perhaps one day a recording might come along where the singers shape their notes as today's historical instrumentalists do in the service of a genuine chamber-music approach – I can only dimly imagine the possible results but I am sure they would be wonderful. I can't, alas, imagine how well-behaved I would have to be for Santa to organize that in the foreseeable future (Audite 21.421, three discs, 2 hours 36 minutes).

http://operalounge.de

| 01.12.2013 | Rüdiger Winter | December 1, 2013

Ein etwas strenges "Weihnachtsoratorium" mit Karl Ristenpart bei audite

Am Anfang war die Pauke

Dieses Weihnachtsoratorium ist nichts für Nebenbei. Sollte es ja eigentlich auch niemals sein. Aber mal ehrlich, wer hat nicht schon mal beimMehr lesen

Auf dem Programm steht eine Ausgrabung, die bei audite rechtzeitig zum Fest erschienen ist: Johann Sebastian Bach, Weihnachtsoratorium, aufgenommen 1950 in Berlin mit Kammerchor, Knabenchor und Kammerorchester des RIAS unter der Leitung von Karl Ristenpart (21.421).Er hatte das Kammerorchester 1946 gegründet. Ristenpart (1900 – 1967), der auch während des Nationalsozialismus künstlerisch tätig gewesen ist, gehörte zu den Pionieren des musikalischen Neubeginns nach dem verlorenen Krieg in Westdeutschland. Seine Aufnahmen sind Legende, einer umfänglichen Kantatenausgabe beim selben Label folgt nun das überfällige Oratorium. Es ist eine historische Aufnahme, nicht nur in Bezug auf ihr Alter von mehr als sechzig Jahren. Der Ansatz ist streng, protestantisch streng. “Soli deo gloria!” Dem alleinigen Gott die Ehre, wie Bach unter seine Werke schrieb. Unbändige Freude will bei so viel Ernst nicht aufkommen. Die ist genauso wie Sinnlichkeit und gar ein Hauch Erotik erst späteren Aufnahmen vorbehalten. Auf dem Weg dahin ist Ristenpart mit seiner Deutung eine wichtige Station. Bei allen kritischen Einwänden, die zu einem Gutteil unseren heutigen Hörgewohnheiten entspringen, gebührt dieser Produktion in der umfangreichen Diskographie des Werkes ein vorderer Platz. Ristenpart nimmt die Chorpassagen ziemlich zügig, lässt sich aber bei der Gestaltung des inhaltlichen Geschehens viel Zeit, als wolle er, dass jedes Detail gebührend zur Geltung gelangt, nichts soll verloren gehen.

Das Solistenquartett fügt sich in dieses Konzept exakt ein – Agnes Giebel (Sopran), Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus (Alt), Helmut Krebs (Tenor), Walter Hauck (Bass). Alle singen alles, Krebs ist auch der Evangelist. Alle haben große Bach-Erfahrungen. Stilistisch bieten sie eine vollkommene Leistung an allen sechs Kantaten. Gern erinnere ich mich an weit zurückliegende Aufführungen des Weihnachtsoratoriums in meiner Jugendzeit in kleinen oder großen Kirchen. Die Sänger hatten stets die Noten in Händen, die wie zum Pult gegen das Publikum erhoben waren. Damals fand ich das etwas albern, später habe ich diese Haltung richtig verstanden. Niemand hätte sich gewagt, seine Partie aus dem Gedächtnis vorzutragen, obwohl das die meisten locker gekonnt hätten. Respekt vor dem Werk zeigte sich auch als Respekt vor dem Notenblatt. Genau so konzentriert und würdevoll wirken die Solisten dieser Aufnahme auf mich.

Wer noch kein Weihnachtsoratorium besitzen sollte und sich endlich eins zulegen will, ist mit dieser Aufnahme nicht gut bedient. Für den Einstieg gibt es unzählige Alternativen neueren Datums. Sie ist ein Sammlerstück, ein sehr wichtiges allemal. Ich möchte nicht mehr darauf verzichten.

BBC Radio 3 | 02.11.2013, 10.20 Uhr | Andrew McGregor | November 2, 2013 BROADCAST CD review

Richard Wigmore joins Andrew live in the studio to discuss recent recordings of music of Johann Sebastian Bach.<br /> <br /> Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!

www.musicweb-international.com | Tuesday November 22nd | John Quinn

Back in 2012 I warmly welcomed a large Audite box containing the surviving recordings of Bach cantatas made between 1946 and 1953 by Karl Ristenpart.Mehr lesen

As I remarked when reviewing his cantata recordings, Karl Ristenpart (1900-1967) was somewhat ahead of his time in that he performed Bach’s choral music with quite small forces, using a chamber orchestra and also a chamber choir comprised of professional singers. Furthermore, his tempi were often closer to those we’re accustomed to hearing from today’s Bach interpreters rather than those usually selected by conductors of Bach in the post-war years such as Karl Richter. The result of all this is that there’s usually a most persuasive feeling of textural lightness to Ristenpart’s Bach and though he can be judiciously measured in the speeds he adopts, the music rarely if ever drags. Whilst I’m wary of over-reliance on timings it’s interesting to note that Ristenpart’s overall timing for this work is not significantly longer than the timing achieved by Sir John Eliot Gardiner on his recording (150:04) or that of Stephen Layton on his brand new Hyperion set (151:49). However, it’s not just a question of timings: one feels that Ristenpart is conveying the spirit of the music.

Ristenpart was discriminating in his choice of soloists and the quartet who sing for him here all featured prominently in his cantata series. It’s worth saying at the outset that none of them ornament the da capo sections of the arias in accordance, I suspect, with the practice of the time. The credentials of Helmut Krebs (1913-2007) as a Bach singer do not need rehearsing here. He was a noted Evangelist and he was the only tenor used by Ristenpart in the cantata recordings that survive. He adds lustre to this performance. He sings the narration very well, the timbre of his voice ideally suited to Bach’s recitative. The narration is often paced quite deliberately – though it never drags – and Krebs makes every word come alive, investing the text with meaning. The clarity of his diction is matched by the clarity of his vocal production so he makes a fine Evangelist. He also does the tenor arias very well indeed; in these numbers his light, athletic voice and an excellent technique are priceless assets,. I particularly enjoyed his rendition of ‘Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben’ where he’s partnered by two equally incisive violinists.

Agnes Giebel (b. 1921) had at least as big a career as Krebs. Like him, she excelled in Bach - and in much else - and she makes a distinguished contribution here. The echo aria, ‘Flöβt, mein Heiland, flöβt dein Namen’ is charmingly done. The music is really suited to Giebel’s voice and she sings it beautifully. She’s aided by the conductor’s astute pacing and by the involvement of a fine oboist. Everything else Giebel does gives comparable pleasure. The name of Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus (1908-1979) is not quite as well known but I enjoyed her singing in the cantata set and she’s on very good form here also.’Bereite dich, Zion’, taken at a pace which is quite steady, reveals not only her pleasing tone but also the conviction of her singing. Her voice is very evenly produced and I admire her sense of line. Equally enjoyable is her unaffected singing in the wonderful aria, ‘Schlafe, mein Liebster’. I was fascinated to note here that Ristenpart, who adopts a very fluent speed, takes 9:55 for this aria; that’s not appreciably slower than Gardiner, who takes 9:20. Layton, in his new recording, takes 10:47 and makes it sound more like a lullaby than either of them.

The baritone is Walter Hauck (1910-1991). He’s another singer who I enjoyed in the cantata set though there he faced competition from the young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. He’s a good singer, though not in the same class as Fischer-Dieskau, even early in the latter’s career. His tone is firm and his voice is consistently well and clearly produced. He’s heard to good advantage in ‘Groβer Herr, O starker König’, which is taken quite steadily. I’ve heard more imaginative accounts of this fine aria but Hauck gives a strong, un-histrionic reading of it. Later on he gives a good performance of ‘Erleucht auch meine finstre Sinnen’ though, once again, it’s not the most nuanced rendition of Bach’s music that I’ve heard. But Hauck is reliable at all times.

The orchestral playing is pretty good – there are some excellent wind players in the band – though the trumpets can be a bit fallible at times. There’s one particularly sour piece of pitching from the first trumpeter on the last chord of the opening chorus of Cantata III. That’s the chorus which is repeated at the end of the cantata and when the exact same flaw is apparent the second time round one doesn’t need to be a super sleuth to deduce that the same take has been recycled. The singing of the RIAS-Kammerchor is decent but not outstanding. I suspect that Habakuk Traber is right to point out in his notes that the choir had not been in existence for all that long and had not been welded into an homogenous ensemble by 1950 – Ristenpart was not their chorus master, by the way. The blend is often not very good and the singing is not always ideally tidy. That said, the choir never lets the side down and they certainly sing with commitment – that’s evident right at the start in a vigorous rendition of the opening chorus of Cantata I, though here one has the sense that the accent is more on demanding our attention rather than on rejoicing. I think the standard of singing improves as the performance unfolds and the choir makes a good job of the opening chorus of Cantata V and an even better fist of the corresponding movement in Cantata VI.

I found Ristenpart’s direction stylish and convincing. Listeners familiar with ‘modern’ performances of the work may think at first that the opening chorus, ‘Jauchzet, frohlocket’ is somewhat steady. True, the music does sound sturdier than it does in the hands of, say, Gardiner. However, my firm advice would be that you should persevere. I don’t think you’ll be far into the work before the conviction of Ristenpart’s view of the piece takes over. And, as I said earlier, I don’t believe that he could never be accused of allowing the music to drag but he certainly conveys its spirit. One thing that slightly surprised me was the assertion in the notes that Ristenpart “chose swift tempi for the chorales.” I don’t really feel the chorales are taken all that swiftly, though they’re certainly not turgid. To my ears they sound comfortably paced and I applaud the conductor’s avoidance of pauses at the fermatas. Instead the chorales have a forward momentum and the phrasing makes sense of the words. I rather think the author of the notes had in mind that in Ristenpart’s hands the chorales were taken more swiftly than was the prevailing practice at the time. There’s one slight disappointment: I’m pretty sure that in Cantata IV Ristenpart has the horn parts played on trumpets, probably for economic reasons.

Given that this performance was recorded sixty-three years ago, albeit under studio conditions, the quality of the recorded sound is bound to be an issue for collectors. All I can say is that Audite have done a splendid job with these transfers. The performers sound to be quite close to the microphones and in that sense the balance is rather up-front. Once or twice the closeness of the balance bothered me a little, one such instance being the soprano/bass duet, ‘Herr, dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen’ (Cantata III) where both of the singers and the pair of oboes d’amore are all a bit too close for comfort – and occasionally Agnes Giebel is slightly disadvantaged in the balance. However, during most of the work the balance is satisfactory and never once did I feel the sound was an obstacle to enjoyment of the performance. That’s a credit both to the original RIAS engineering team and to Ludger Böckenhoff, who has re-mastered these tapes and who was also one of the two re-mastering engineers behind the Ristenpart cantatas box.

Karl Ristenpart was a remarkable Bach conductor, truly years ahead of his time. This recording of the Christmas Oratorio, set down over a mere two days, is not flawless – not least because performing standards have risen so much during the last sixty years. However, it’s stylish, wise and very well worthwhile hearing. I’m absolutely delighted that Audite have not just rescued this fine recording from the vaults but that they have done such an excellent presentational job in issuing it. Unfortunately, though, unlike the set of cantata recordings, no texts are provided. I suppose it’s too much to hope for that there are any more Ristenpart Bach performances in the archives but this present issue is a most welcome addition to the discography of Bach’s Christmas masterpiece.