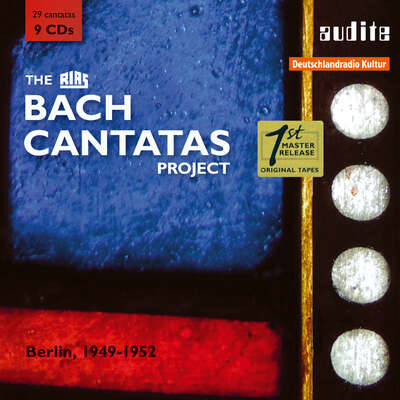

Die 9 CD-Box mit Erstveröffentlichungen aus dem RIAS-Archiv präsentiert den historisch ersten Versuch einer Gesamteinspielung der Bach-Kantaten. Für jeden, der sich für die Geschichte der Bach-Interpretation und für die Linien des kulturellen Wiederaufbaus in Deutschland nach dem Zweiten...mehr

RIAS Kammerorchester | RIAS Kammerchor | RIAS Knabenchor

"Deshalb ist diese Box insgesamt nicht nur für denjenigen, der sich explizit für die Geschichte der Bach-Interpretation interessiert, von hoher Bedeutung. Auch wer das „alte“ Klangbild als solches oder die Gesangsstimmen der Vergangenheit gern hört, wird sich über so manchen sehr schönen Track auf diesen CDs freuen. Sehr zu hoffen ist, dass noch weitere Kantaten aus der Ristenpart-Aufnahmeserie auf CD erscheinen." (Rondo)

Titelliste

Details

|

The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project

The first ever attempt at a recording of the complete Bach cantatas, Studio recordings from Berlin (1949-1952) |

|

| Artikelnummer: | 21.415 |

|---|---|

| EAN-Code: | 4022143214157 |

| Preisgruppe: | BRC |

| Veröffentlichungsdatum: | 9. März 2012 |

| Spielzeit: | 630 min. |

Zusatzmaterial

-

Producer's Comment

unmittelbare Eindrücke des Produzenten Ludger Böckenhoff

-

Pressemappe Bach-Kantaten

mit umfangreichem historischen Material dieser Veröffentlichung

- Portrait of a Baritone_Listen 092012

Informationen

Die 9 CD-Box mit Erstveröffentlichungen aus dem RIAS-Archiv präsentiert den historisch ersten Versuch einer Gesamteinspielung der Bach-Kantaten.

Für jeden, der sich für die Geschichte der Bach-Interpretation und für die Linien des kulturellen Wiederaufbaus in Deutschland nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg interessiert, sind die Aufnahmen in dieser CD-Box eine bedeutende Bereicherung. Karl Ristenpart baute ab 1946 die Chor- und Orchesterarbeit des RIAS Berlin auf und leitete den RIAS Kammerchor und das RIAS Kammerorchester. Mit diesen Ensembles und aufstrebenden jungen Sängern wie Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Helmut Krebs und Agnes Giebel planten Karl Ristenpart und Elsa Schiller, die damalige Leiterin der RIAS Musikabteilung, ab 1947 eine Gesamteinspielung aller Bach-Kantaten. Das Projekt konnte allerdings nicht vollständig verwirklicht werden. Die heute noch im RIAS-Archiv vorhandenen 29 Kantaten dokumentieren ein auch aus heutiger Sicht zukunftsweisendes Bach-Ideal: durch die kleine Besetzung erscheint die Musik transparent und strukturell deutlich, die Sänger kooperieren klar artikulierend mit den Instrumentalisten. Durch diese Interpretation, die sich von aller Monumentalität frei macht, wurde die spätere historische Aufführungspraxis ästhetisch vorbereitet.

Zu dieser Produktion gibt es wieder einen „Producer's Comment" vom Produzenten Ludger Böckenhoff unter

http://www.audite.de.

Die Produktion ist Teil unserer Reihe „Legendary Recordings" und trägt das Qualitätsmerkmal „1st Master Release". Dieser Begriff steht für die außerordentliche Qualität der Archivproduktionen bei audite, denn allen historischen audite-Veröffentlichungen liegen ausnahmslos die Originalbänder aus den Rundfunkarchiven zugrunde. In der Regel sind dies die ursprünglichen Analogbänder, die mit ihrer Bandgeschwindigkeit von bis zu 76 cm/Sek. auch nach heutigen Maßstäben erstaunlich hohe Qualität erreichen. Das Remastering - fachlich kompetent und sensibel angewandt - legt zudem bislang verborgene Details der Interpretationen frei. So ergibt sich ein Klangbild von überlegener Qualität. CD-Veröffentlichungen, denen private Mitschnitte von Rundfunksendungen oder alte Schellackplatten zugrunde liegen, sind damit nicht zu vergleichen.

Besprechungen

Saarländischer Rundfunk | SR 2 KulturRadio: Samstag, 21. Dezember 2013 | Josef Weiland | 21. Dezember 2013

Die originalen Rundfunk-Tonbänder wurden einem professionellen Remastering unterzogen, um die bestmögliche Klangqualität zu erreichen. Und da kommt man – auch bei diesen CDs – tatsächlich ins Staunen, was die Techniker heutzutage alles möglich machen.Mehr lesen

Muzykalʹnaya zhiznʹ | N° 3 2013 | Ilya Ovchinnikov | 1. März 2013

Russische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

http://operalounge.de

| Dr. Gerd Heinsen | 30. November 2012

Bei audite eine 9 CD-Box

Bach von Ristenpart

Ristenparts Bach-Kantaten bei audite – ein Wiederhören mit legendären Sängern der Berliner Nachkriegszeit im RIAS Berlin 1949 – 1952. DieMehr lesen

Neben der Dokumentation des Schaffens von Karl Ristenpart, zu Unrecht heute vergessen und gern fälschlich als Mittelklasse-Dirigent abgeschrieben, beschert diese bedeutende audite-Produktion eben ein Wiederhören mit den ebenso wichtigen Sängern der Berliner Nachkriegszeit. Neben so bekannten wie Giebel oder Dieskau finden sich hier Gertrud Birmele oder die stimmige Gunthild Weber, die viel mit dem Berliner Dirigenten Werner auftrat und eingespielt hat, auch Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus – eine bedeutende Altistin jener Jahre – und natürlich Helmut Krebs, der Allround-Tenor der Berliner und Hamburger Opernhäuser und unerreichter Interpret für die Moderne ebenso wie fürs Barocke. Ein Cornocupium also an exzellenten Sängern und eine wichtige Korrektur unserer Wahrnehmung jener Zeit, die wir heute nur noch wegen ihrer Schallplattensänger der DGA oder Electrola in Erinnerung haben, als es noch die Exklusivbindungen gab. Wie in anderen europäischen Ländern auch (namentlich Italien und Frankreich) korrigierte das Radio diesen Exklusiv-Eindruck und bot die weniger glücklichen Sänger, die keinen Fuß in den Plattenfirmen hatten.

www.musicweb-international.com | 31.12.2012 | John Quinn | 31. Dezember 2012 Recordings Of The Year 2012

Either this has been a particularly rich year or else I’ve been extremely fortunate in the quality of the discs that have come my way for review. MyMehr lesen

All the releases that I’ve chosen, which I’ve deliberately listed in alphabetical order – and those mentioned above – have given me particular pleasure and I hope that if you acquire them they’ll have the same effect on you.

Johann Sebastian Bach: The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project

This set was a revelation: Bach cantatas recorded between 1946 and 1953 but in a style that puts the performances closer to that of the period performance revolution that lay years ahead. The conductor, Karl Ristenpart, used a chamber choir and orchestra and the results are light and fresh. Outstanding among the soloists are Agnes Giebel, Helmut Krebs and the young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Ristenpart conducts with great distinction and with a real feeling for the spirit of Bach. These performances constitute a major addition to the discography of Bach’s cantatas.

[…]

Mitteilungsblatt der Neuen bachgesellschaft

| Winter 2012 | Sabine Näher | 1. Dezember 2012

Buch- und CD-Tipps

The RIAS BACH CANTATAS Project

Noch ein paar Jahre vor den Motetten in Leipzig wurden in Berlin dieseMehr lesen

Classica | n°146 (octobre 2012) | Philippe Venturini | 1. Oktober 2012

Dans le Berlin en ruines de l’après-guerre, il fallait aussiMehr lesen

Scherzo | 01.10.2012 | Alfredo Brotons Muñoz | 1. Oktober 2012

En la resurrección de la música en Alemania tras la II Guerra MundialMehr lesen

Das Orchester | 09/2012 | Arnold Werner-Jensen | 1. September 2012

Diese umfangreiche CD-Box ist imponierend in editorischer und musikalischerMehr lesen

Deutschlandfunk | Dienstag, 28. August 2012, Nachtkonzert, 02.05-3.00 Uhr | Bernd Heyder | 28. August 2012

Meilenstein der Bach-Interpretation

Das Kantatenprojekt von Karl Ristenpart und dem RIAS Berlin (1947 – 1952)

Die erste Stunde des Nachtkonzerts ist einem außergewöhnlichen Aufnahmeprojekt gewidmet, das vor mehr als sechs Jahrzehnten, in denMehr lesen

Musik 1)

Johann Sebastian Bach

aus der Kantate „Es erhub sich ein Streit“, BWV 19:

Eingangschor (Auszug)

Das waren der RIAS-Kammerchor und das RIAS-Kammerorchester mit einem Ausschnitt aus dem Eingangschor von Johann Sebastian Bachs Kantate „Es erhub sich ein Streit“, Werk-Verzeichnis 19; die Leitung hatte Karl Ristenpart. Die Aufnahme stammt aus dem Jahr 1950. Sie war Teil eines Einspielungsprojektes, das vier Jahre zuvor in der Musikabteilung des gerade gegründeten RIAS Berlin seinen Anfang genommen hatte. Der „Rundfunk im Amerikanischen Sektor“ war von der amerikanischen Militäradministration als unabhängige Gegenstimme zum sowjetisch kontrollierten Berliner Rundfunk ins Leben gerufen worden. Weit über die Grenzen der Stadt hinaus sendete der RIAS Berlin in die sowjetisch besetzte Zone. Von Anfang an gehörten sonntägliche Sendungen mit geistlicher Musik zum Programmauftrag.

Da das Schallarchiv des Senders erst allmählich aufgebaut wurde und man anfangs kaum auf ältere Tonträger zurückgreifen konnte, war es wichtig, die benötigten Aufnahmen selbst zu produzieren. Und da beschloss die von Elsa Schiller geleitete Musikabteilung, sämtliche etwa 200 Kirchenkantaten Bachs mit den hauseigenen Ensembles einzuspielen; die künstlerische Umsetzung sollte in den Händen von Karl Ristenpart liegen.

Den im Jahr 1900 geborenen Dirigenten hatten die amerikanischen Behörden 1946 mit dem Aufbau der Rundfunk-Klangkörper betraut. Ristenpart hatte in den 20er Jahren am Stern’schen Konservatorium in Berlin und an der Wiener Akademie der Tonkunst studiert und 1932 in Berlin ein eigenes Kammerorchester gegründet. Neben seinen musikalischen Qualitäten empfahl ihn nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg sicher auch die Tatsache, dass er sich 1933 geweigert hatte, der NSDAP beizutreten, obwohl das seiner Dirigentenkarriere damals sicherlich dienlich gewesen wäre. Wie sein Vorbild Hermann Scherchen faszinierte Ristenpart die zeitgenössische wie die ältere Musik gleichermaßen – und in letzterem Bereich insbesondere Johann Sebastian Bach.

Beim RIAS Berlin baute Ristenpart neben dem Symphonierochester und dem Tanzorchester auch ein Kammerorchester auf. Es bildete für ihn das ideale Ensemble für seine Interpretationen barocker Musik, und das nicht nur im rein instrumentalen Repertoire: Auch in der Aufführung Bach’scher Vokalwerke ging Ristenpart in deutliche Distanz zu den seinerzeit gängigen Monumentalbesetzungen. Ebenso lehnte er aber jene sachlich-distanzierte Deutung dieser Musik ab, wie sie damals von vielen Vertretern der anti-romantischen Bach-Bewegung favorisiert wurde.

In der folgenden Aufnahme des Eingangssatzes aus der Kantate „Wer sich selbst erhöhet, der soll erniedriget werdet“ mit seinen ausgedehnten Instrumentalritornellen lässt sich gut verfolgen, wie Ristenpart seinen Ansatz mit dem RIAS-Kammerorchester verwirklichte und wie er ihn auch auf den Vokal-Bereich übertrug.

Musik 2)

Johann Sebastian Bach

aus der Kantate „Wer sich selbst erhöhet, der soll erniedriget werden“, BWV 47:

Eingangschor

In einer Aufnahme von 1952 hörten Sie den Eingangschor der Kantate „Wer sich selbst erhöhet, der soll erniedriget werden“ von Johann Sebastian Bach, interpretiert vom RIAS-Kammerchor und -Kammerorchester unter Karl Ristenpart.

Als Aufnahme-Ort für die Kantatenproduktionen des RIAS Berlin etablierte sich die Jesus-Christus-Kirche im Stadtteil Dahlem, ein 1932 geweihtes Gotteshaus, das sich in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus zu einem Zentrum der Bekennenden Kirche entwickelt hatte. Bis heute dient die Kirche neben ihrer religiösen Funktion auch als Aufnahmestudio, unter anderem für Produktionen des DeutschlandRadios, zu dem sich der RIAS Berlin 1994 gemeinsam mit dem Deutschlandsender Kultur und dem Deutschlandfunk formierte.

Karl Ristenpart stellte den Chor mit etwa drei Dutzend Sängern für die Bach-Projekte zunächst immer wieder neu zusammen; erst im Oktober 1948 erhielt er seine institutionelle Form. Vereinzelt setzte Ristenpart neben den Erwachsenenstimmen des Kammerchores aber auch die jungen Sänger des RIAS-Knabenchores ein. Die Einstudierung der vokalen Ensemblesätze vertraute er den Chorleitern Herbert Froitzheim und Günther Arndt an.

Aus Ristenparts relativ kleinen Chor- und Orchesterbesetzungen spricht der Wunsch, Bachs Musik sehr detailgenau und doch in ihrer ganzen Expressivität hörbar zu machen. Dazu suchte er auch Vokalsolistinnen und –solisten mit klaren und flexiblen Stimmen, und schnell fand er im Ensemble der Deutschen Oper in West-Berlin zwei herausragende Sänger für die Tenor- und Bass-Partien: Helmut Krebs und Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Der 1913 in Aachen geborene Krebs konnte schon auf Vorkriegs-Erfolge an der Berliner Volksoper zurückblicken. Der 22-jährige Fischer-Dieskau hatte gerade mit der Einspielung von Schuberts „Winterreise“ für den RIAS Berlin sein Rundfunk-Debüt absolviert, als er im Februar 1948 erstmals in Ristenparts Bach-Projekt mitwirkte. Im folgenden Ausschnitt aus dem zweiten Teil der Kantate „Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes“ BWV 76 sind nacheinander Fischer-Dieskau als Rezitativ- und Krebs als Ariensänger zu hören.

Musik 3)

Johann Sebastian Bach

aus der Kantate „Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes“, BWV 76:

Rezitativ „Gott segne noch die treue Schar“

Arie „Hasse nur, hasse mich recht“

Der Bariton Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau und der Tenor Helmut Krebs sangen zwei Sätze aus Bachs Kantate 76, begleitet vom RIAS-Kammerorchester unter Karl Ristenpart. Die Aufnahme entstand im Mai 1950. Unmittelbar darauf spielte Fischer-Dieskau unter Ristenpart auch die Eingangsarie der Kantate 88 ein, „Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden“. Sie zählt zu den schönsten Soli, die Bach für die tiefe Männerstimme schrieb, auch wenn sie nicht die Berühmtheit seiner Solo-Kantaten oder der Bass-Partien aus den Passionen erlangt hat. Dem alttestamentlichen Text folgend führt sie dem Hörer zunächst eine Szene am Wasser und dann eine Jagdszene musikalisch vor Augen; in Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau und dem RIAS-Kammerorchester fand sie kongeniale Interpreten – wenn auch die Hornpartien in der Aufnahme merkwürdig diffus abgebildet sind.

Musik 4)

Johann Sebastian Bach

aus der Kantate „Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden“, BWV 88:

Eingangsarie

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sang die Eingangsarie der Kantate „Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden“ BWV 88; es begleitete das RIAS-Kammerorchester unter Karl Ristenpart.

Während man Fischer-Dieskau und den Tenor Helmut Krebs fast schon als Stammsänger der damaligen Kantaten-Aufnahmen des RIAS Berlin bezeichnen könnte, war eine deutlich größere Zahl von weiblichen Solisten daran beteiligt. Unter ihnen ragte eine junge Sopranistin mit ihrer schlanken, hell timbrierten Stimme und ihrer natürlichen Deklamation hervor: Agnes Giebel. [Schnell erwarb sie sich den Ruf einer der besten Bach-Sängerinnen; der Oper verweigerte sie sich konsequent.] Mit ihr als Solistin gestattete sich Ristenpart im Juni 1951 auch einen Ausflug ins weltliche Vokalrepertoire Bachs, als er die Sopran-Solokantate „Weichet nur, betrübte Schatten“ aufnahm.

Musik 5)

Johann Sebastian Bach

aus der Kantate „Weichet nur, betrübte Schatten“, BWV 202:

Arie „Sich üben im Lieben“

Agnes Giebel sang die Arie „Sich üben im Lieben“ aus Bachs Sopran-Solokantate „Weichet nur, betrübte Schatten“, BWV 202.

Nicht alle der Aufnahmen des Bach-Projektes beim RIAS Berlin sind erhalten geblieben. Viele der Produktionen aus den 40er Jahren wurden schon 1950 wieder gelöscht, vermutlich, um Aufnahmen auf höherwertigem Bandmaterial Platz zu machen. Auch war man wohl rein musikalisch auf einem Interpretationsniveau angelangt, das es nahelegte, das eine oder andere Werk noch einmal neu aufzunehmen – was dann mit 25 Kantaten geschah.

Auch für die Bach-Forschung stellte das Jahr 1950 einen Wendepunkt dar; es war die Geburtsstunde der Neuen Bachausgabe, die auf der Basis einer erneuten Analyse der überlieferten Notenquellen neue Erkenntisse für die Werkchronologie und die Aufführungspraxis gewann. Davon konnten Ristenparts Produktionen aber noch nicht profitieren, die mit dem Notenmaterial der einhundert Jahre zuvor initiierten „alten“ Bach-Gesamtausgabe arbeiten mussten. Der Dirigent stand aber im engen Kontakt zu Bach-Forschern wie Friedrich Smend und Gotthold Frotscher.

Es fällt auf, dass Ristenpart durchgängig das Cembalo anstelle der Orgel als Generalbassinstrument einsetzt; vielleicht lag das aus rein praktischen Gründen nahe. Bemerkenswerter ist sicherlich seine Entscheidung, die Mehrzahl der Blockflöten-Partien in den Kantaten auch wirklich mit Blockflöten zu besetzen und nicht, wie viele andere Dirigenten damals, von Querflöten spielen zu lassen. Den Eingangschor der Kantate 39, in dem zwei Blockflöten im Wechsel mit zwei Oboen und den Streichern zu Anfang das Brotbrechen symbolisieren, hatte man zuvor im 20. Jahrhundert wohl kaum in einem entsprechend plastischen Klang gehört:

Musik 6)

Johann Sebastian Bach

aus der Kantate „Brich den Hungrigen dein Brot“, BWV 39:

Eingangschor

Das war der Eingangssatz der Kantate 39, „Brich den Hungrigen dein Brot“, in der Interpretation Karl Ristenparts von 1950; es handelt sich um eine der frühesten Kantaten-Aufnahmen, in denen die originale Blockflötenbesetzung zu hören ist.

So groß der Elan war, mit dem das Kantaten-Projekt beim RIAS Berlin vor allem im Bach-Jahr 1950 mit allein 47 Einspielungen vorangetrieben wurde, so stark erlahmte das Engagement in der Folgezeit: von 1951 bis zur letzten Produktion am 13. Februar 1953 wurden gerade einmal neun weitere Kantatenaufnahmen produziert. Die amerikanischen Behörden hatten aus finanzpolitischen Gründen die Auflösung der RIAS-Orchester verfügt. So ging Ristenpart im Sommer 1953 zum Saarländischen Rundfunk, und ihm folgten viele Mitglieder seines Kammerorchesters. Dort entstanden dann vor allem Einspielungen des instrumentalen Bach-Repertoires, teilweise in Kooperation mit einer französischen Schallplattenfirma und wohl auch mit Rücksicht auf deren Kundenkreis.

So blieb das Berliner Projekt unvollendet; noch mehr als drei Jahrzehnte sollte es dauern, bis der Dirigent Helmuth Rilling mit seiner Gächinger Kantorei und dem Bach Collegium Stuttgart die Kantaten Bachs in einer Gesamteinspielung auf Schallplatte vorlegte; Ende der 80er Jahre brachten dann auch Nikolaus Harnoncourt und Gustav Leonhardt nach fast zwanzig Jahren ihr gemeinsames Einspielungsprojekt der Kirchenkantaten Bachs zum Abschluss – zum ersten Mal auf historischen Instrumenten.

Jede der erhaltenen Aufnahmen Ristenparts ist in sich künstlerisch geschlossen, und viele von ihnen wirken immer noch überraschend modern in ihrer detailreichen und recht flüssigen Interpretationsweise – mag man heute, da sich die historische Aufführungspraxis weitestgehend etabliert hat, auch schnellere Tempi und stärker von der schwingenden Rhythmik der Takthierarchien geprägte Klangbilder barocker Musik gewöhnt sein.

Am Beispiel der Bach-Kantate zum Trinitatisfest 1725, „Es ist ein trotzig und verzagt Ding“, soll am Ende unserer Sendung deutlich werden, wie es Ristenpart verstanden hat, die Binnendynamik und die innere Dramaturgie einer solchen mehrsätzigen und entsprechend vielgestaltigen Komposition zur Geltung zu bringen. Die Aufnahme stellt Ihnen zugleich noch drei weitere Vokalsolisten des RIAS-Projektes vor: Gerda Lammers (Sopran), Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus (Alt) und Gerhard Niese (Bass).

Musik 7)

Johann Sebastian Bach

Kantate „Es ist ein trotzig und verzagt Ding“, BWV 176:

Mit Johann Sebastian Bachs Kantate 176, „Es ist ein trotzig und verzagt Ding“, gingen die „Historischen Aufnahmen“ zu Ende, in denen wir Ihnen heute das Bach-Kantatenprojekt des RIAS Berlin aus den späten 1940er und frühen 1950er Jahren vorstellten. Sie hörten den RIAS-Kammerchor und das RIAS-Kammerorchester unter der Leitung von Karl Ristenpart; die Solisten in der Kantate 176 waren Gerda Lammers (Sopran), Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus (Alt) und Gerhard Niese (Bass). Im Studio verabschiedet sich Bernd Heyder mit Dank für Ihr Interesse.

WDR 3 | Freitag, 17.08.12 um 09:08 Uhr, Klassik Forum | Hans Winking | 17. August 2012

Historische Aufnahmen:

Das RIAS Bach-Kantaten-Projekt 1949-1952

Schon lange bevor die sog. „Historische Aufführungspraxis“ mit ihremMehr lesen

www.huffingtonpost.com

| July 31, 2012 | Laurence Vittes | 31. Juli 2012

The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project

29 Bach cantatas conducted by Karl Ristenpart, Berlin 1949-52

One of the first things the Americans did when gaining a foothold in BerlinMehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | Friday July 6th | John Quinn | 6. Juli 2012

Recording of the month

Johann Sebastian BACH (1685-1750): The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project

These recordings form a remarkable part of the immediate post-war musical legacy in what was then West Germany. The background, which is related moreMehr lesen

The very thorough notes in the booklet relate the whole story behind these recordings in good detail. In all 78 cantatas were recorded between October 1946 and February 1953; in fact, 107 recordings were made but some recordings were subsequently duplicated. The recordings were made for a wider use than the ‘merely’ musical; they were broadcast during a Sunday morning religious programme on RIAS when the cantata appropriate to the day would be heard after a sermon. Quite a number of the earlier recordings were ’wiped’ and I infer from the essay by Rüdiger Albrecht that, regrettably, what we have in this box is all that survives. It will be noted that many of the cantatas here included are not among the cantatas that are better-known, even today. Also, there are frustrating gaps. There is no BWV 147, for example, and I noted that one of the earliest recordings was a performance of BWV 82 by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; what one would give to hear that!

It must be remembered that at the time of these performances the Bach cantatas were far from being widely known, so this project was hugely enterprising and the driving force behind it was Karl Ristenpart. His career was focused principally on chamber orchestras – he founded his own ensemble as early as 1932. It appears that he was unsympathetic to the Nazis – which would have made him acceptable for RIAS – although he did agree to take his orchestra to play for the troops at the front during the war years. He set up the RIAS Kammerorchester and when policy changes at RIAS brought about the demise of that orchestra – and the Bach cantata project – in 1952 he moved to Saarbrücken to work for the radio station there, setting up another chamber orchestra, including some of his Berlin players. During his fourteen years there, however, the emphasis was on orchestral music so no more Bach cantatas were forthcoming.

In many ways Ristenpart was ahead of his time, especially in using fairly small forces to perform Bach. That’s one reason why these performances are of such interest to Bach collectors. We aren’t told the approximate size of either the choir or the orchestra but both are clearly smaller than the ensembles used by Karl Richter in his Bach recordings for DG Archiv. Another attraction lies in the roster of soloists. Many of the names will be unfamiliar sixty years or so later but three names stand out. Among the sopranos was Agnes Giebel (b. 1921) then starting out on her career. Though Ristenpart engaged several singers in the other three voices he used just one tenor, at least on these recordings, namely Helmut Krebs (1913-2007). Krebs was a soloist at the Deutsche Oper at this time. A few years later he recorded a good deal of Bach with Fritz Werner but here we find him in younger voice. Incidentally, Agnes Giebel was another luminary of those fine Werner recordings of Bach. It’s a joy to hear so much of these two excellent Bach singers but the set is invaluable also because we can hear a good many examples of the young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Born in 1925, Fischer-Dieskau would have been in his mid-twenties when these recordings were made. News of the great singer’s death was announced while I was evaluating these discs and much has been spoken and written – and very rightly so – about his immense stature as one of the foremost singers of the second half of the twentieth century. Like Krebs, he was at this time a soloist with the Deutsche Oper but Bach’s music was a constant thread throughout his career and it’s thrilling to have so many examples of his early work in this box; one can readily understand why his singing caused such a stir from the very start of his career for he is in consistently magnificent voice.

Let me discuss some highlights from this engrossing set and start with one of the finest performances of all, that of Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140. This is, quite simply, an outstanding Bach performance. The opening chorus is impelled forward most excitingly. When the choir first enters their call of ‘Wachet auf’ is a true wake up-call; and what an inspired decision by Ristenpart to have the boys of the RIAS Knabenchor joining the soprano line and lending the cutting edge of their tone to the melody! There’s real enthusiasm and urgency here. Ristenpart’s tempo seems ideal to me and he takes 6:24 over the movement. Out of curiosity I put on Karl Richter’s 1978 DG Archiv recording, to which I hadn’t listened in a long time. Oh dear! His tempo is insufferably slow in this movement – he takes 9:38 – and in his hands the music sounds turgid and uninspiring. Fritz Werner too is pretty stately – he takes 8:14 but at least he’s not as leaden as Richter. I revelled in Ristenpart’s reading which, frankly, would not sound out of place among today’s ‘period’ performances. In the following recitative Krebs sounds like a clarion herald. In the famous tenor chorale movement Ristenpart uses the whole tenor section from the choir – which I prefer. Richter uses his soloist, which is perhaps understandable when you have Peter Schreier on hand to do the honours but again a lethargic speed rules out this version while Ristenpart seems to get it just right. The soprano soloist for Ristenpart is Gunthild Weber who is an effective partner to Fischer-Dieskau in the two duets. Fischer-Dieskau also sings for Richter. There he’s partnered by the enchanting Edith Mathis. I prefer her to Weber but I prefer Fischer-Dieskau’s singing on the Ristenpart recording. Although there are many satisfying cantata performances in this box this one, I think, takes the palm.

Another conspicuous success is Agnes Giebel’s account of the solo Wedding Cantata, Weichet nur, betrübte Schatten, BWV 202. She’s in wonderful form here, singing the opening aria with fine expression – and partnered by a good oboist. She’s delightfully eager-sounding in the second aria, where a perky bassoon obbligato also gives much pleasure. The late Alfred Dürr says that the third aria “strikes a more elegiac note”. Far be it from me to dissent from the view of such an expert but I don’t hear elegy in this music and certainly not in Giebel’s warm, radiant singing of it. The fourth and final aria, decorated by a pert oboe part, sounds smiling and happy here and the concluding gavotte movement is charming.

There’s another solo cantata in the set, Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, BWV 56, which features Fischer-Dieskau. Here, in 1950, we find him in wonderful voice, even throughout its compass and with a lovely ease at the top of his register. He recorded it also with Richter, in 1969, and I prefer Richter’s slightly more flowing tempo in the opening aria but, on the other hand, I prefer the smaller band employed by Ristenpart. Fischer-Dieskau’s tone is superb in 1969 but in that later version he is more emphatic in his enunciation of the words. The cantata includes the joyful aria ‘Endlich, endlich wird mein Joch’. Both performances are excellent but I find Fischer-Dieskau sounds just a bit more natural and spontaneous for Ristenpart.

What of Helmut Krebs? He’s splendid throughout no matter what tests Bach sets him and no matter what emotions he’s required to convey. A stand-out moment for me is the aria ‘Ermuntre dich’ in BWV 180. This is a very demanding aria but Krebs is quite outstanding – and the flute obbligato is jolly good too. Krebs’ voice is light and keen and the rhythms dance irresistibly. His articulation is tremendous and I love his light, ringing tone. This is an outstanding piece of Bach singing by anyone’s standards. In BWV 19 there’s a very different test for a Bachian tenor in the aria ‘Bleibt, ihr Engel, bleibt bei mir’. Krebs sustains the long lines excellently and I admire his control very much. That said, even he doesn’t match the wonderful way in which James Gilchrist, a very different singer, floats the line at a daringly expansive tempo in Vol 7 of Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s Bach Cantata Pilgrimage. For me, Gilchrist and Gardiner capture the essence of this music in a way that’s very special. Krebs appears in every one of the cantatas that require a tenor and his singing gives unfailing pleasure. Not only that, he is a stylist and, additionally, a singer who cares about the words and knows how to put them across. His heady, distinctive tone and consistently clear diction are a delight to hear.

The other soloists aren’t quite so well known, at least not in 2012, but there are few weak links. One or two of the sopranos aren’t really to my taste. Edith Berger-Krebs (the wife of the tenor?) sings in BWV 42, where she duets with Helmut Krebs and, quite honestly, isn’t in his class; her tone sounds rather pinched and shrill. Lilo Rolwes is somewhat tremulous of tone in her aria in BWV 31 and in BWV 21 Gerda Lammers sounds to me to be striving a bit too much for expression and, as a result, the line is rather choppy. The altos are all effective. I particularly enjoyed the contributions of Ingrid Lorenzen – she gives a fine account of the extensive alto aria in BWV 42, for instance – while Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus has a good focus to her voice as she shows, for example, in BWV 22. Walter Hauck and Gerhard Niese have to stand retrospective comparison with Fischer-Dieskau, which is a bit unfair, but both acquit themselves well in their various assignments.

The singers of the RIAS-Kammerchor make a strong contribution. Sometimes the sound is a little fuzzy but I wonder if this is as much to do with the recordings as the singing itself. I’ve already mentioned their excellent contribution to BWV 140. Another place where they feature to particularly good effect is the dramatic opening chorus of BWV 19, which they deliver with plenty of energy and punch. They give a good performance of BWV 4 as well – I liked the lively tempo and good choral response in the first chorus. Richter in 1968 has better sound, of course, but his choir is bigger – some may prefer, as I do, the smaller ensemble – and yet again Richter’s speed is steadier than Ristenpart’s. Incidentally, in the fourth chorus of this cantata Ristenpart gets all his basses to sing whereas Richter uses a solo voice (Fischer-Dieskau). I think Richter’s decision is the correct one but against the pleasure of hearing Fischer-Dieskau sing the piece we must set yet another leaden tempo by Richter, who lingers over the movement for 4:36 against Ristenpart’s much more satisfactory 2:45.

The RIAS-Kammerorchester plays well for Ristenpart although those schooled on ‘period’ performances will need to adjust their ears for the string vibrato and the legato style of playing. There’s some good obbligato playing and it’s a pity that the players concerned aren’t named; I suspect there isn’t a full record of who played in the orchestra.

The presiding genius is Karl Ristenpart and these recordings show him as a Bachian of perception, style and good taste. I’m a great admirer of Eliot Gardiner in the Bach cantatas – and of Fritz Werner too. Eliot Gardiner can be brisk in his tempi but I can recall very few instances in this set where I felt Ristenpart was too slow. In any event, tempo is about more than speed; it’s about finding the pace that’s right for the music and, in vocal music, for the sentiments expressed in the words. Here I think Ristenpart’s judgement is pretty well always spot-on. I said at the start of this review that he was ahead of his time and this is especially true of his determination to use slimmed-down forces at a time when this was far from being the norm. This, together with the fact that he articulates rhythms so well brings to his performances a fine clarity of texture and excellent energy.

As to the recorded sound, I think it’s astonishingly good, especially when one considers that these recordings were made sixty or more years ago. Clearly the RIAS engineers knew what they were doing. Audite’s re-mastering engineers, Ludger Böckenhoff and Karsten Zimmerman, who have worked from the original tapes, deserve plaudits for such fine work. Their skill has been vital in allowing today’s listeners to experience so satisfactorily the integrity, dedication and sheer excellence of Karl Ristenpart’s performances.

These performances constitute a major addition to the discography of Bach’s cantatas. Their reappearance after all these years is a cause for rejoicing. This is one of the most important Bach issues for many years and the set is urgently commended to all who love Bach’s cantatas.

Musik & Theater | 07/2012 | Werner Pfister | 1. Juli 2012 Lebendige Vergangenheit

Nach dem Krieg, als alles daniederlag und rundum mit AufbauarbeitenMehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | July 2012 | Andrew McGregor | 1. Juli 2012

A groundbreaking pilgrimage

CD Review's Andrew McGregor explores an undeservedly forgotten JS Bach Cantata project

When it comes to JS Bach's Cantatas on disc, the deservedly famous Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt series for Telefunken was first toMehr lesen

The 29 Cantatas chosen here are fascinating. Ristenpart pioneered many of the enlightening ideas of Harnoncourt and Leonhardt's series: small forces, a well-drilled choir sometimes with boys' voices, a focus on detail, and emotional engagement with the texts. The soloists are well chosen, and one name leaps out: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, just a couple of years into his career. He's immediately recognisable. The set's only tenor, Helmut Krebs, has the timbre and communicative qualities of a German Peter Pears. The pick of the eight sopranos is Agnes Giebel, who makes a lovely job of her duets with the virtuoso oboe soloist in one of Bach's wedding Cantatas, BWV202, while the Actus Tragicus is seriously moving. Wachet auf is urgent and theatrically potent: a success. While some movements might be on the slow side for today's authentic performers, others are brisk and crisp. The recordings are sometimes shockingly good for their age, and these performances stand apart from anything else around for a good 20 years. Changes at RIAS brought this revelatory project to a premature end in 1953, but at least this intriguing box should ensure that Ristenpart is restored to his rightful place as a Bach pioneer.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung am Sonntag | 03.06.2012 | Franz Cavigelli | 3. Juni 2012 Nach dem Krieg

Not lehrt nicht nur beten, nein, auch Kantaten singen. 1947 fasste man imMehr lesen

Gramofon | June 2012 | Rob Cowan | 1. Juni 2012

Inspiration floating on the airwaves

Bach cantatas from Audite and the Bach Guild; anniversary releases for Walter, Solti and Kreisler

Back in the late 1940s, Berlin's 'Radio in the American Sector' (RIAS) setMehr lesen

www.opusklassiek.nl | juni 2012 | Aart van der Wal | 1. Juni 2012 Het Bach-cantateproject: de RIAS-opnamen 1949 ~ 1952

Deze uit de archieven van de RIAS (Rundfunk Im Amerikanischen Sektor)Mehr lesen

Early Music Review | No. 148, June 2012 | Beresford King-Smith | 1. Juni 2012 The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project, Berlin, 1949-1952

On the strength of an enthusiastic BBC Radio 3 review by the much respected Nicholas Anderson, I lashed out and bought this 'Audite' boxed set: 9 CDsMehr lesen

I did already have a few 'historic' Bach Cantata recordings, including some fascinating (if incomplete) performances recorded in Leipzig's Thomaskirche under the direction of Karl Straube in 1931 (the year when I was born!) The style may sound a bit quaint to us, now, but it affords an interesting glimpse into the past. I also have some recordings made by the Thomanerchor in the early 1950s under its post-war Kantor, Günther Ramin, but they too seem of Iittle more than historical interest today. So – it was a big surprise to put on these newly-issued Berlin CDs, remastered from tapes which date from around 1950, and to discover how "modern" and thoroughly enjoyable many of the performances sound.

Following Berlin's almost total destruction at the end of the war, its radio stations had to start from scratch. RIAS stands for 'Radio in the American Sector'; the RIAS-Symphonie Orchester was formed in 1946, the RIAS-Kammerchor two years later. From 1946 onwards, Karl Ristenpart started directing regular Sunday broadcasts of Bach Cantatas, using a chamber orchestra drawn from the RSO. Recordings of his very earliest performances no longer exist, but from the end of 1949 until the Project ran out of steam in 1952, we have tapes of 29 Cantata performances, now superbly transferred to CD in this boxed set.

The overall quality of performance is truly remarkable, with some first-class vocal soloists, outstanding amongst whom are Helmut Krebs (as good and incisive as any Bach tenor I know) and a young baritone then just making his mark: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. In 1950, when the majority of these recordings were made, he would have been just 25. In May 2012, of course, we were all saddened to learn of his death at the age of 86. To hear him in the superb opening aria of Cantata 88 (Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden) is an absolute delight, and the orchestral accompaniment is of admirable quality, too. In Cantata 52 (Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht), soprano Agnes Giebel is very stylish, the high horns sounding fine in the opening Sinfonia (borrowed from Brandenburg I). But the real hero of the hour is unquestionably Karl Ristenpart himself; he has a happy knack of finding, nine times out of ten, what Bach calls the tempo giusto.

There are some infelicities, of course. Most of the female soloists (Giebel apart) do favour the use of a fairly heavy vibrato – that was the accepted style at that time. The choir is enthusiastic, but not very subtle – it's at its best in high-energy numbers like the opening chorus of Wachet auf, which fairly dances along in a most enjoyable way; occasionally, though, it goes well over the top (try Cantata 176: Es ist ein trotzig und verzagt Ding – the text does suggest desperation and obstinacy, but the oft-repeated word tro-o-o-o-o-otzig still sounds pretty laughable). The four-part Chorales are sung with great gusto, but JSB will [may CB] have expected his congregation to join in, so he probably wouldn't have been too dismayed by that.

The keyboard continuo instrument used is a harpsichord, whose tone-quality does sometimes remind one of Sir Thomas Beecham's unkind description: 'two skeletons copulating on a tin roof'! Fortunately, it's kept well back from the microphones. No 'shortened' continuo accompaniment, of course – the cello is often left sustaining very long notes on its own, as was normal up until the 1960s or thereabouts. But, overall, the instrumentalists are extremely good – for example, some superb violin obligati, a terrific first trumpeter, some lovely flute-playing in Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele and delightful recorders in Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot. The oboes do sound a bit under-nourished (as they often did, in those pre-Helmut-Winschermann days) but that's a small price to pay for some revelatory recordings from a vanished era. Strongly recommended

Classical Recordings Quarterly | Summer 2012 | Graham Silcock | 1. Juni 2012

The 28 cantatas here – plus one by Telemann, thought to be Bach's at the time of the recording – are a selection from a huge project which wasMehr lesen

To all this can be added some relevant technical detail. All the recordings here were made in the twentieth-century Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin-Dahlem, on magnetic tape. Tape recording was of good and consistent quality in Germany even by 1945; so much so that the BBC was still using captured German tape machines as late as 1952. In West Germany there was a much earlier move to FM radio than elsewhere in Europe, largely because of the poor allocation of AM channels to the whole country by the Copenhagen agreement of 1950. Many of the early recordings were re-made as the quality of the tapes improved, because the faults in the older ones became more obvious on FM radio. A noticeable improvement in quality can be heard in this selection which, by 1950 – the Bach bicentenary year – became at least comparable with commercial recordings of the period. During that year 21 of these 28 Bach recordings were made.

The first impression – and it is one that will surprise those who have been persuaded by exaggerated claims for "period" performances is of the relative modernity of the instrumental playing and (to a lesser extent) of the choral singing. The scale of these performances is very much as it would now be but, of course, there are no period instruments. Except for odd moments from the solo singers there is an absence of unwelcome overt "expressiveness". From the instrumentalists there is remarkable, adroit and attractive playing. The many obbligato soloists in the arias give great pleasure. There is the very occasional disaster, as with the solo trumpet which descants the final chorus of No. 31 and is painfully out of tune.

Mention of trumpet playing – elsewhere never less than adequate – brings me to the choral singing. In both there is a tendency to "punch out" fast semiquavers note by note with the chorus aspirating every one of them, although there are not many such passages. Another anachronism is the use of a harpsichord in the basso continuo. By the end of the 1950s this had been banished in sacred music by a chamber or positive organ.

Among the soloists there are some outstanding singers who went on to international careers. The focused and very spiritual voice of Agnes Giebel (Nos. 47, 32, 108, 52, 79, 202) is perhaps the finest among the sopranos but Gunthild Weber – less consistent – is also often memorable (Nos. 58, 76, 199, 164, 140). Ingrid Lorenzsen, who takes many of the alto solos sometimes sings with the kind of vibrato that now sounds anachronistic in Bach. All the tenor roles are taken by Helmut Krebs, whose effortless, articulate voice seems ideal for this music. Some of his numbers are extremely challenging, none more so than the aria "Hasse nur, hasse mich recht" in No. 76 where even he resorts to aspirating the swirling melismatic passages. Finally – and for some his presence will be decisive – there is much characterful and meaningful singing from the young Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, whose first commercial recordings coincided with this collection. From April 1950 comes Cantata No. 37 from which the recitative and aria "Ihr Sterblichen ... Der Glaube schafft der Seele Flügel" stands as an arresting exemplar of the quality of Fischer-Dieskau's early style.

One cannot hear these performances without sometimes reflecting on the straitened and austere environment out of which they sprang in ruined post-war Germany. Never more is this so than in No. 21, Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, recorded in the early summer of 1950. From the opening Sinfonia (Adagio assai) to the final chorus with its resplendent trumpets and drums we follow the despairing soul down into the abyss. Through the central Christian notion of its union with God the journey then leads through the motet-like chorus "Sei nun wieder zufrieden" to final joy.

Among the other works it is often the betterknown that leave the most Iasting impression. No. 140, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme has the RIAS boys' chorus singing its cantus firmus followed by Helmut Krebs's exultant recitative beginning "Er kommt". No. 79 is also notable for its (splendidly recorded) opening chorus in a style close to Händel and the direct simplicity of Lorri Lail's alto aria with flute obbligato that follows it.

Throughout the series we are aware that we are listening to history as well as to music. The ultimate hero of the project is surely Karl Ristenpart himself, whose later work with the Saarland Chamber Orchestra brought excitement and quality to the label Club Français du Disque and also deserves to be heard again.

www.klavier.de

| 14.05.2012 | Johanna Schubert | 14. Mai 2012

Bach, Johann Sebastian: The Rias – Bach Cantatas Project

Ein Stück deutscher Musikgeschichte

Audite veröffentlicht mit dem RIAS-Kantaten-Projekt ein ambitioniertesMehr lesen

klassik.com

| 14.05.2012 | Johanna Schubert | 14. Mai 2012 | Quelle: http://magazin.k...

Bach, Johann Sebastian – The Rias - Bach Cantatas Project

Ein Stück deutscher Musikgeschichte

Audite veröffentlicht mit dem RIAS-Kantaten-Projekt ein ambitioniertesMehr lesen

Il Venerdi di Repubblica | 11.05.2012 | Claudio Strinati | 11. Mai 2012 Quandϙ Berlino si senti libera ascoltando Bach

Una delle prime preoccupazioni del comando americano, nella BerlinoMehr lesen

BBC Radio 3 | 05.05.2012, 10.15 Uhr | Andrew McGregor | 5. Mai 2012 BROADCAST CD review

Nicholas Anderson jions Andrew to discuss recent Bach box sets<br /> <br /> Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!

Junge Freiheit | Nr. 19/12 | 4. Mai 2012 | Sebastian Hennig | 4. Mai 2012 Klage und Lobpreis

Die Erschließung der Schatzkammern des Deutschlandradios hat das LabelMehr lesen

orpheus | Heft 5+6 (Mai/Juni 2012) | G.H. | 1. Mai 2012

Ristenparts Bach-Kantaten bei audite – ein Wiederhören mit legendären Sängern der Berliner Nachkriegszeit im RIAS Berlin 1949-1952. Die auditeMehr lesen

Financial Times - Deutschland | Montag, 23. April 2012 | Dagmar Zurek | 23. April 2012 Rias Kammerorchester und Chor

Die schlanke Stimme des damals noch jungen Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau istMehr lesen

Suplimentul de Culturâ | Anul VIII, Nr. 351 (7–13 aprilie 2012) | Victor Eskenasy | 7. April 2012 Karl Ristenpart şi „Proiectul Cantatelor Bach“ (Audite)

În ajun de Paşti, Audite, o companie germană, specializată îndeosebiMehr lesen

www.europalibera.org

| 05.04.2012 | Victor Eskenasy | 5. April 2012

Proiectul RIAS al Cantatelor de Bach

Dirijorul Karl Ristenpart și un proiect cultural germano-american din anii 1946-1952.

In ajun de Paști, „Audite”, o companie germană, specializată peMehr lesen

RBB Kulturradio | 04.04.2012 | Kai Luehrs-Kaiser | 4. April 2012 Das RIAS Bach-Kantaten Projekt

Von 1949 bis 1952 entstanden die hier versammelten 29 Bach-Kantaten mit dem frühen RIAS-Kammerchor, dem RIAS-Kammerorchester (mit Musikern desMehr lesen

Fundstücke

Wir haben es mit einer Fundgrube einer Pioniergeneration von Bach-Aficionados zu tun. Und doch muss man sogleich einschränkend hinzufügen, dass etwa der – inzwischen weltberühmte – RIAS-Kammerchor um die Zeit von 1950 herum noch nicht das war, was er heute ist. Sein Ruf geht auf spätere Zeiten, nicht zuletzt auf die Aufbauarbeit von Günther Arndt (ab 1954) und vor allem von Uwe Gronostay zurück (ab 1972). Noch Gronostay sagte mir vor Jahren, als er den Chor seinerzeit übernahm, habe noch das Witzwort vom „RIAS-Jammerchor“ offen kursiert. Von Homogenität, Klangschönheit oder Textverständlichkeit kann daher nur eingeschränkt die Rede sein. Der Chor klingt – für heutige Ohren – eher wie ein Laienchor. Auch die technischen Standards der Instrumentalisten und sogar der Solisten erinnern daran, dass man die hochempfindlichen Rundfunk-Mikrophone offenbar noch nicht ganz gewohnt war.

Von historischem Wert

Trotzdem enthält die Sammlung z.B. die Erstaufnahme der „Kreuzstab“-Kantate mit Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau aus dem Jahr 1950 und eine Vielzahl von Einspielungen, die unter Sammler-Aspekten allerhöchstes Interesse verdienen. Die am Legato-Ideal Wagners orientierten, aber klein besetzten Aufnahmen vermitteln ein völlig anderes Bach-Bild als etwa der (etwas spätere) Karl Richter dies tat. Insofern doch von historisch erheblichem Wert!

International Record Review | April 2012 | Nicholas Anderson | 1. April 2012

Karl Ristenpart's recordings of a dozen or so of Bach's cantatas, dating from the late 1950s and early to mid-1960s, are probably well known to loversMehr lesen

Meanwhile, we must be grateful for the 29 cantatas, albeit one of which is by Telemann, which have been preserved and now most skilfully transferred to CD from the original analogue tapes, rather than 78rpm records. Listening to them has been a veritable epiphany, for not only did Ristenpart clearly have ideas well ahead of his time but also the discernment to engage what were probably the two finest German Bach Singers available to him. These are the late Helmut Krebs and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, not forgetting a very young Agnes Giebel. Krebs sings in all the cantatas requiring tenor voice, Fischer-Dieskau in comfortably over half of those containing recitatives and arias for bass.

Though I well remember an icy-cold day on a railway station platform in Berlin-Dahlem in 1977, when Krebs told me about these recordings, he never intimated that any of them were still in existence. I assumed they were not, and so this box of treasures has been affording particular delight, both for its element of surprise but, above all, for the pleasure generated by the imaginative and individual musicianship of Ristenpart, his soloists and instrumentalists.

Compared with those of Karl Richter and Fritz Werner, Ristenpart's choir is small, bringing with it effective degrees of lucidity and athleticism. The vocal diction is enunciated with clarity by choir and soloists alike, a feature by which Ristenpart evidently set some store. Internal balance is well maintained for the most part and it soon becomes apparent that textural transparency in which instruments and voices are allowed to converse without having to compete was of prime consideration. All this is par for the course nowadays, but in the late 1940s and early 1950s it comes as something of a surprise to hear such a light-footed, chambermusic approach to Bach. With only one or two exceptions Ristenpart favours brisk tempos; indeed his Christ lag in Todesbanden (BWV 4) knocks a full half-minute off Masaaki Suzuki's (BIS).

It is inevitable that in a sizeable clutch of cantatas such as this not everything will come across uniformly well – the clipped articulation of the voices in some of the choruses is dated, though in Ristenpart's hands by no means inexpressive, as you can hear in the opening chorale fantasia of Herr Jesu Christ, wahr' Mensch und Gott (BWV 127). It is a pity, too, that occasionally da capos are shortened, but such instances are exceptions rather than the rule. Any other lapses are few and far between, often, I suspect, deriving as much from the limitations of recording technique as from any shortcomings in the artists themselves.

It is wonderful to hear Krebs in his prime. Seldom do we encounter recitatives sung with such urgent communication and such poetry as he had at his command, though just occasionally even he sounds uneven, as in the exacting tenor aria of Es ist euch gut, dass ich hingehe (BWV 108). In this lyrical piece it is Peter Pears who has the edge in an early recording with Karl Richter (Teldec-Warner). The youthful Fischer-Dieskau likewise seldom disappoints and then only with a hint of excessive vibrato, but almost entirely without the declamatory extravagances which occasionally caricature his later recordings with Karl Richter. Giebel's intimately expressed and radiantly coloured singing is already in place, though her voice is not fully matured and her performance of Weichet nur, betrübte Schatten (BWV 202) is less evenly controlled than her later version with Gustav Leonhardt (Teldec-Warner). There are other fine voices here aplenty, from among which I should mention soprano Gunthild Weber, who was a regular of Fritz Lehmann's (DG Archiv) in the early 1950s, soprano Johanna Behrend and contralto Charlotte Wolf-Matthäus, who made some notable contributions to the Bärenreiter-Cantate series of Bach's cantatas during the early 1960s. However, though listed among the soloists, soprano Edith Berger-Krebs does not, in the event, take part in any of these recordings.

In summary, here is an anthology which cannot fail to enchant most Bach enthusiasts. Readers will find cantatas which few if any other of the early pioneers committed to disc: BWV 88, for instance, with its twin images of the fishermen and huntsmen in its opening aria, sung with robust theatricality by Fischer-Dieskau. lch hatte viel Bekümmernis (BWV 21) is among the most poignant that I know, Krebs and Fischer-Dieskau firmly impressing a stamp of immortality upon Ristenpart's performance. Likewise, Wachet auf! ruft uns die Stimme (BWV 140), whose opening chorale fantasia is as thrilling as any I can recall. What a pity that the booklet omits the name of every single instrumentalist. Surely some of them, at least, must be known and if so they certainly should be included here since they play such a prominent role in the music. Ristenpart, by the way, remains faithful to Bach's precise instrumentation almost without exception, only preferring flutes to recorders, doubtless for practical reasons, in the opening chorus of Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele (BWV 180).

Audite must be congratulated on this invaluable rehabilitation. At times one can scarcely believe the modernity of approach and in all but one or two instances the excellence of the sound. A revelation.

Das Opernglas | April 2012 | J. Gahre | 1. April 2012 CD-SPECIAL

Der RIAS-Sender (Radio im amerikanischen Sektor) war erst wenige MonateMehr lesen

Pizzicato | N° 222 - 4/2012 | RéF | 1. April 2012 Für Sammler Pflicht

Die hier von Audite vorgelegten Aufnahmen von 29 Bach-Kantaten waren Teil eines Projekts, das Karl Ristenpart 1947 beim RIAS Berlin initiierte: dieMehr lesen

Für Bach-, Ristenpart- und FischerDieskau-Sammler ist diese Veröffentlichung ein Pflichtkauf.

Mannheimer Morgen | 22.03.2012 | urs | 22. März 2012 Bewegend

Fast unmittelbar nach dem Zusammenbruch im Verlauf des Zweiten WeltkriegsMehr lesen

Rondo | Nr. 722 / 10. - 16.03.2012 | Michael Wersin | 10. März 2012

Das hat es noch nie auf CD gegeben: In den Jahren 1949 bis 1952 spielte derMehr lesen

Paulinus - Wochenzeitung für das Bistum Trier | 10/2012 | Christoph Vratz | 4. März 2012 Bach im Nachkriegs-Berlin

Ab 1946 baute Karl Ristenpart die Chor- und Orchesterabteilung des RIAS inMehr lesen

Der neue Merker | 01.03.2012 | 1. März 2012 The Bach Cantatas Project von Audite

Die 9 CD-Box mit Erstveröffentlichungen aus dem RIAS-Archiv präsentiertMehr lesen

DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton | 27.02.2012 | Claudia Dasche | 27. Februar 2012

Klassik: "The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project"

Originalbänder aus dem RIAS-Archiv

Neun CDs umfasst die Box "The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project". Sie ist nicht nur ein musikalisches Ereignis, sondern veranschaulicht zugleich denMehr lesen

Der Dirigent Karl Ristenpart leitete ab 1946 den RIAS Kammerchor und das RIAS Kammerorchester. Gemeinsam mit vielen Solisten, darunter die Sopranistin Agnes Giebel und der junge Baritonsänger Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, wurden 29 Kantaten aufgenommen. Für die Erstveröffentlichung der RIAS-Bach-Kantaten-Edition wurden die Originalbänder aus dem RIAS-Archiv verwendet, die in der Zeit zwischen 1949 und 1952 entstanden.

Die Einschätzungen unserer Musikkritikerin:

Die Einspielung aller erhaltenen und rekonstruierten Kantaten Johann Sebastian Bachs als Gesamtedition der Öffentlichkeit vorzulegen wäre nicht nur ein spektakuläres Unternehmen, sondern wahrscheinlich auch eine Lebensaufgabe.

Es handelt sich dabei um mehr als 200 Vokalwerke, die Bach's Biographie, seine kompositorische Entwicklung und Auseinandersetzung mit theologischen wie weltlichen Themen von Beginn an widerspiegeln. Karl Ristenpart hat sich als Leiter des RIAS-Kammerorchesters- und Chores an dieses Großprojekt gewagt und 1947 mit den ersten Aufnahmen begonnen.

"Nur" 29 Kantaten wurden letztlich realisiert; dokumentieren aber auf ganz eindrucksvoller Weise, wie nahe sie mit ihrer Interpretation bereits der heute gängigen Bach'schen Aufführungspraxis kamen.